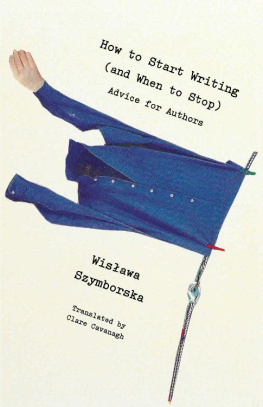

How to Start Writing

(and when to stop)

All works by Wisawa Szymborska copyright 2000, 2021 by the Wisawa Szymborska Foundation

Translation and introduction copyright 2021 by Clare Cavanagh

Originally published in Polish as Poczta literacka, czyli jak zozsta (lub nie zosta) pisarzem, ed. Teresa Walas

Published by arrangement with the Wisawa Szymborska Foundation (www.szymborska.org.pl)

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

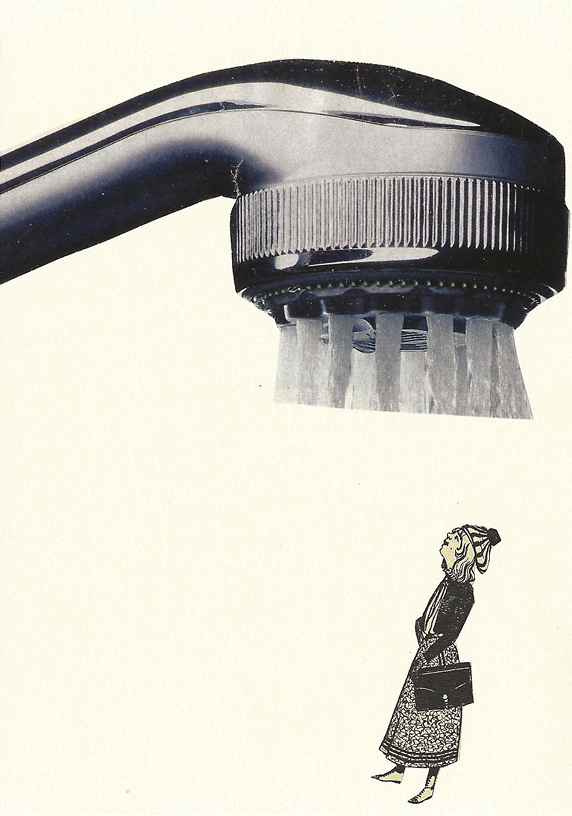

The Szymborska collages are from Clare Cavanaghs collection of postcards from the author and are reproduced here by permission of the Wisawa Szymborska Foundation.

Excerpts from In Praise of My Sister, Stage Fright, and Under One Small Starare from Map: Collected and Lost Poems by Wisawa Szymborksa, translated from the Polish by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh. English translation copyright 2015 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

The quotation from Rilke on p. 42 is from Letters to a Young Poet, translated by M. D. Herter Norton (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1934).

Manufactured in the United States of America

First published as New Directions Paperbook 1514 in 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Szymborska, Wisawa, author. | Cavanagh, Clare, editor, translator.

Title: How to start writing (and when to stop) : advice for writers / Wislawa Szymborska ; edited, translated, and with an introduction by Clare Cavanagh.

Other titles: Poczta literacka, czyli jak zosta (lub nie zosta) pisarzem. English

Description: First edition. | New York : New Directions Publishing, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021022390 | ISBN 9780811229715 (paperback) |

ISBN 9780811229722 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Authorship. | Creative writing. | Feuilletons, Polish. | LCGFT: Essays.

Classification: LCC PG7178.Z9 P5813 2021 | DDC 891.8/5473dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021022390

New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin

by New Directions Publishing Corporation

80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011

I dedicate this translation to Drenka

best of editors & best of friends

c.c.

.

The Use and Abuse of Poetry for Life

or, Wisawa Szymborskas dos

and donts for would-be writers

What would American poets and critics do without the Central Europeans and the Russians to browbeat themselves with? Maureen McLane exclaimed in the Chicago Tribune some years back: Miosz, Wisawa Szymborska, Adam Zagajewski, Zbigniew Herbert, Joseph Brodsky here we have world-historical seriousness! Weight! Importance! Even their playfulness is weighty, metaphysical, unlike barbaric American noodlings! For some time now, Anglo-American authors have tended to see Eastern Europe, with its twentieth-century sufferings, as a perverse promised land for modern writing, with Poland in particular serving as a kind of shorthand for The Oppressed Country Where Poetry Still Matters. I will not attempt to speak for all the poets McLane has assembled here. Szymborska for one, though, would be shocked to find herself ranked among the metaphysically serious and universally significant world powers of modern poetry.

She celebrates the joy of writing in one famous lyric. She is even more persuasive on the highly underrated joy of not writing she extols in In Praise of My Sister:

When my sister asks me over for lunch,

I know she doesnt want to read me her poems.

Her soups are delicious without ulterior motives.

Her coffee doesnt spill on manuscripts.

Szymborska is preoccupied here, as throughout her work, with the relationship between poetry and the daily life that surrounds it, feeds it, and sometimes altogether ignores it. She has nothing but sympathy for the labors of would-be writers generally: My first poems and stories were bad too, she confesses in an interview with her friend Teresa Walas. The texts that make up her typically idiosyncratic How to (and How Not to) guide are culled from the advice she gave anonymously for many years in Literary Mailbox, a regular column in the Polish journal Literary Life.

She deals less gently, though, with those who scorn the sheer drudgery it takes to do anything well, be it soup-making or sonnets. You write, I know my poems have many faults, but so what, Im not going to stop and fix them, she chides one novice, a certain Heliodor from Przemyl: And why is that, oh Heliodor? Perhaps because you hold poetry so sacred? Or maybe you consider it insignificant? Both ways of treating poetry are mistaken, and whats worse, they free the novice poet from the necessity of working on his verses. Its pleasant and rewarding to tell our acquaintances that the bardic spirit seized us on Friday at 2:45 p.m. and began whispering mysterious secrets in our ear with such ardor that we scarcely had time to take them down. But at home, behind closed doors, they assiduously corrected, crossed out and revised those otherworldly utterances. Spirits are fine and dandy, but even poetry has its prosaic side. (Szymborska used the first-person plural not as the queenly prerogative of a future Nobel Laureate, but to maintain her anonymity, since Polish grammar relentlessly reveals its users gender, and she was the only woman on Literary Lifes editorial staff who answered letters.)

She goes no easier on would-be novelists. You have compiled an extensive list of writers whose talent went unrecognized by editors and publishers who later shamefacedly repented, she tells a certain Harry, from Szczecin: We instantly caught your drift and read the enclosed feuilletons with all the humility our errors warrant. Theyre old hat, but thats not the point. They will certainly be included in your Collected Works so long as you also produce something along the lines of David Copperfield or Great Expectations.

Poor Welur from Chem gets even shorter shrift: Does the enclosed prose betray talent? It does.

Translators, for what its worth, fare no better. The translator must not only stay faithful to the text, she scolds H. O. from Pozna: He or she should also reveal the poems full beauty while retaining its form and suggesting the epochs style and spirit. In your version, Goethe becomes a writer whose odds of achieving world glory are slim.

True, luard did not know Polish she tells Luda from Wroclaw: But did you have to make it so obvious in your translations?

Poets are poetry, writers are prose, Szymborska comments in her resolutely antipoetic Stage Fright or so public opinion would have it.

Prose can hold anything including poetry,

but in poetry theres only room for poetry

In keeping with the poster that announces it

with a fin de sicle flourish of its giant P