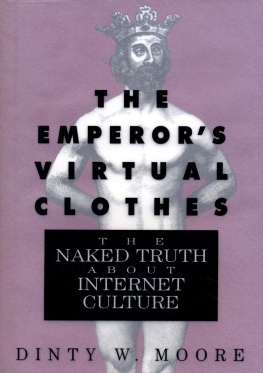

The Emperors Virtual Clothes

The Naked Truth about Internet Culture

by Dinty W. Moore

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Published by

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

1995 by Dinty W. Moore.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

E-book ISBN 978-1-56512-861-3

For Benita Marie Romasco

Acknowledgments

My deepest gratitude to the many individuals who so willingly shared their experiences, both on and off the Net. Without them, there would be no book. I would also like to thank Kjell Meling and Pennsylvania State University for their support, Bruce Weigl for his encouragement, George Romasco for lending me my first computer, and Robert Rubin for his trust in my ability to enter the electronic woods and not get hopelessly lost.

Since most of what we are told about new technology-comes from its proponents, be deeply skeptical of all claims.

Jerry Mander, In the Absence of the Sacred

Everybody gets so much information all day long that they lose their common sense.

Gertrude Stein

Contents

Preface

INTO THE ELECTRONIC WOODS

Or, Whats the Big Deal, Anyway?

The National Mall sweltered, the humidity was impenetrable, and thunderstorms boomed and rolled just across the Potomac, so I shuffled into line behind an unruly swarm of overheated, overstimulated, overspent tourists heading for the Smithsonians National Museum of American History. It was air-conditioned, it was free, they had Archie Bunkers chair.

I had long wanted to see that chair and maybe get a quick glance at Edgar Bergens wooden pal Charlie, but once inside the museum, I instead found my eye drawn to a big blue sign:

Information Age: People, Information & Technology

I was in our nations capital for a reason, pursuing some sensible explanation for the sudden explosion of interest and speculation about the so-called Information Superhighway. Why, I wanted to know, was everyone from Vice President Al Gore on down so sure this would change the world? Why was every magazine, newspaper, and television chat show suddenly treating the Internet as if it were the Second Coming of some electronic messiah? What was the big deal, anyway?

Moments before, in the Gerald R. Ford House Office Building, I had listened politely as eager congressional staffers stuffed my brain full of utopian visions of democracy unleashed. They tried to explain, held up statistics, but the picture was far from clear. I was reaching a point where the more I knew, the less I understood.

To clear my head, Id hoped to take a relaxing journey through the Golden Age of Television; but instead duty called: the Age of Information was beckoning to me again, with additional info. I took a deep, long breath and was directed by the sign into a hallway lined with glass cases.

At the exhibits start, I saw a crude machine: Samuel F. B. Morses telegraph, the beginning of instantaneous communication in America. From there, the corridor led me rapidly past old telephone poles, a mannequin family crowded around an enormous art deco radio, a blurry early television with a screen the size of a small watermelon, and finally into the Computer Age, with its ponderous mainframes, vacuum tubes, and banks of tangled wires.

To my considerable disappointment, though, the much-heralded Internet was represented by a single computer terminal, and that terminal was stuck under a glass box. Did the Smithsonian know something I didnt? Was the Information Superhighway so dangerous? I noted that the computers keyboard had been removed as well, in case the glass should break.

A small white exhibit card underneath the imprisoned computer promised this:

By using the telephone to connect their home computers to those of information companies, people can shop for groceries, exchange messages, pay bills, move money between bank accounts, and play computer games.

Dangerous? Hardly. Not even revolutionary. The Smithsonians display made the Internet sound like nothing more than a cross between the Home Shopping Network and Nintendo. I stared at the blinking screen and thought, for the moment at least, that perhaps I had found the truth. Would the Information Superhighway be nothing more than a glorified ATM machine with laser blasters? Was it destined to become yet one more diabolical method by which retail conglomerates moved the point of sale a step closer to our wallets? Was the rest just so much hype?

On that oppressive July afternoon, it seemed I was the only person in the Smithsonian who really cared. The crowds of tourists ignored the glass box, jamming themselves instead around a nearby exhibit on high-definition television. The sleek screen displayed a pair of cumbersome Japanese sumo wrestlers facing off on a blue mat. As the wrestlers tossed themselves to and fro like a pair of shaved bears, the tourists grinned, pointed, and nodded their complete approval. The only information revolution they wanted, it would seem, was one with a really clear picture, a really big screen, and really big men trying to knock one another down.

The Information Superhighway. The Internet. The new frontier that science fiction writer William Gibson dubbed cyberspace. Whatever you call the network of networks that links upward of 35 million computer users worldwide, it is certainly bigger than a sumo wrestler, bigger than an arena full of sumos. Estimates are that someone new plugs into the Internet on the average of every ten minutes, and that dizzying rate of growth is itself expected to increase. In fact, based on current growth rates, some have estimated that every person on the planet will be networked by the year 2003. Soon, they say, we will all be hooked in, turned on, electronically joined at the hip.

But what will it mean?

If you believe the proponents, the zealots, those who not only love computers but see them as mankinds salvation, this amazing phenomenon will in the very near future transform our culture, alter the political process, rearrange the balance of world power, and change the way we think, the way we learn, the way we fall in love. Experts, armed with bits of bright, shiny jargon, assert in no uncertain terms that the Internet will change absolutely everything, right down to the fundamental ways in which we relate as human beings.

On the other hand, oracles of doom see nothing but evil: international computer sabotage, government agents snooping into every aspect of our lives, anti-government anarchists exchanging plans for making bombs, pornography in every home, a world filled with anemic drones laboring away at sterile keyboards, never seeing the light of day, never tossing a Frisbee to their dog. The Internet, it seems, is the final nail in mankinds coffin, a glowing nail, sharp as a tack but evil through and through.

So, who is right? Which will it be?

I think, if you will excuse my using technical terminology here, that both sides are full of hooey.

When it comes to the Information Superhighway, this much is clear: one sides overstatement rapidly drowns out the other sides hyperbole, and that hyperbole is itself instantaneously suffocated under a smothering layer of gross media exaggeration. No one really knows, in other words. They are all just guessing.