,

, ,

P.Oxy.III.1903, no. 425, p. 72

(For translation see )

The genesis of this book has been peculiar and its aim in doubt. For the last sixty years I must have read every popular book that anyone ever wrote about Egypt. In common with my generation I found a deep and so to say natural attachment to things not so much just Egyptian as Ancient Egyptian. Perhaps for us all, the supposed immobility of ancient Egypt stood over against the change which is the experience of daily life. This was not quite a yearning for a lost paradise but it was certainly a yearning for something or other. Perhaps we could divide the children of that generation into those who read Conan Doyle for choice and those who read Rider Haggard. The concept is attractive. You can, by falsifying the nature of both men somewhat, put them at opposite ends of a spectrum. On the one hand, we have the creator of that egotistical male, Sherlock Holmes, and on the other hand we have the creator of She Who Must Be Obeyed. Here we have set up as an ultimate the logic of deduction, there we have Mystics Who Know and do not Need To Reason. And so on. It would not do, of course, for Conan Doyle was the one who ended up looking at photographs of little girls in Art Nouveau costumes and believing they were fairies. We may be simplistic but life isnt. Nevertheless there was in the two men a tendency towards one rather than the other of two worlds.

Haggard, of course, was hooked on the mystery of Darkest Afric. Of this mystery Egyptian history was no more than an extension. His novels TheMoonofIsrael,TheWorldsDesire and Cleopatra either imported or recognized what was implied in our view of ancient Egypt the mystery of magic, the presence of gods, the power of a priesthood, the attraction of ancientry, the glamour of kingship. Then into this partly realized connection between us and them was stirred a catalyst, the excitement, the hullabaloo, the world interest of Tutankhamuns tomb.

Now though I read Conan Doyle when he came my way, I did not buy him and I did not borrow him even from the library. But on Haggard I would spend my all, walk miles for one of his books, read and reread without end. I still think he has scenes of an overwhelming power. C. G. Jung, in the days when not just a diminishing group of addicts but everyone took him seriously seemed to give Haggard a validation. He cited She Who Must Be Obeyed as the archetype of the Anima.

But to us as children and adolescents what was Egypt to be? The young Farouk was to be seen on a stamp, unlikely looking heir of the pharaohs. There was the administration of Egypt by Great Britain, such a benefit to the place. There were the papyri. There were the biblical connections. There were in every museum some of the anthropomorphic, the mummiform coffins that stared at us with all the awesomeness of death, magic, terror, mystery. Yet the official source of all our views of ancient Egypt came by way of archeologists who were just beginning to use science and adopt a wholly rational approach to it science and rationalism in the service of magic and mystery! It was a great confusion.

My childhoods stance, then, was romantic though terrified, even a bit religious though pagan. Mummies, the mere thought of mummies, put ice on my skin, but at the same time I could more readily believe in Ra, Isis and Osiris than in the Trinity. To me the contradictions of Egyptian beliefs were not implausible; or rather, since they were religious beliefs, contradictions were just what I had come to expect.

Yet all the time, as far as the adult world was concerned my preoccupations were with the rationally explored and logically treated discoveries of scientific archeology! This was a tension of which I was only partly aware and which died a natural death as I grew older and was more caught up in life and love around me than in an imaginative dialogue with death and magic.

And yet !

It would be going too far to say that I felt myself to be an ancient Egyptian. But I felt a connection, an unusual sympathy. It became, absurdly enough, a feeling of responsibility as if I owed the country something though I had never been there. There is even the possibility that this book is an unsuccessful attempt to pay that debt.

So there remained a link with ancient Egypt in me until past my middle years. It was only then and about ten years before the publication of this book that my wife and I made our first visit to Egypt. Why so late? At any time in the previous twenty years we could have gone. But there had turned out to be so many interesting things to do, so many other countries to visit, such boats to sail, such money, such reputation to be chased.

Nevertheless, at last go we did and I found that the Egypt of the mind simply did not exist. I had to rearrange everything. Egypt was more much more! Even the archeologists were not what I had supposed. For instead of being the rational creatures I had anticipated they were as crazily imaginative and as well disposed to the Mystery as any child could have wished sixty years earlier. When, for example, the question arose of a dear lady who believed herself to have been a priestess of a particular temple, they did not dismiss her as a crackpot but agreed that shehadsomething.

Then well, a year ago I was approached and asked to write a book on Egypt. The prospect of another visit to Egypt but this time with a Minder who spoke the language (what our Victorian forebears would have called a courier) was attractive. But I had no particular view, had no axe to grind, had read widely but not deeply. I pointed out to the publishers that the book could not be authoritative. To my surprise they were aware of this. It was to be, I found, a book about me as much as about Egypt. It would contain photographs, mostly photographs of the country but some of me.

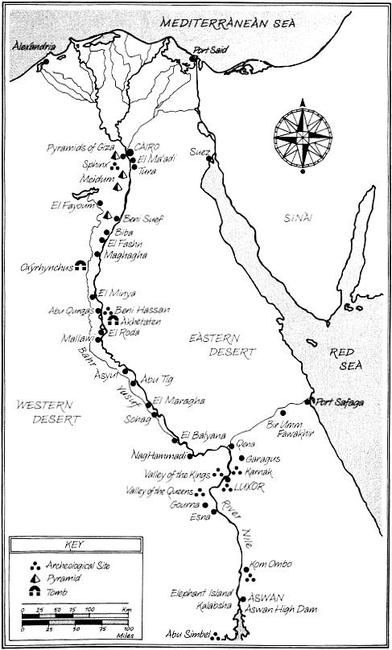

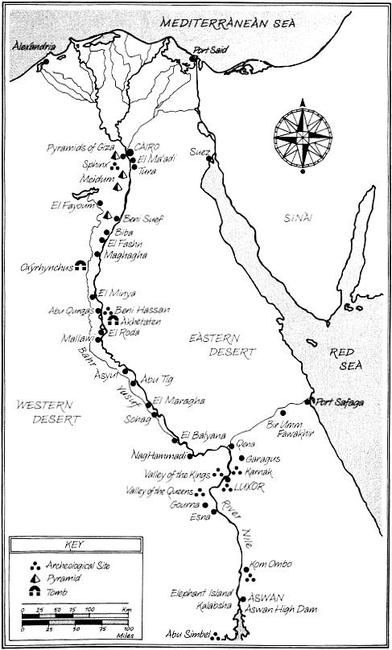

This seemed to be the perfect assignment. We discussed methods. I had an idea which seemed plausible. The last time my wife and I had been in Egypt the greatest difficulty and danger we had faced was to get rooms in hotels. I was, or had been, a sailor. I sailed in my youth, spent the war years in the navy, some of them in command, spent more years after the war teaching sea cadets to sail. After that I sailed my own boat on the north coast of Europe and topped the lot off as unpaid hand in my sons canal boat. Then why not hire a boat, a yacht on which we could live, proceeding up and down the Nile, stopping off at such places of interest as Oxyrhynchus and Abydos; and mingling light-heartedly with live Egyptians instead of dead ones. For during our previous visit I had come to a simple truth; that Egypt is a complex country of more-or-less Arab culture and it is outrageous for the uninformed visitor to confine himself to dead Egyptians while the strange life of the valley and the desert goes on all round him. The tourist (and I was not quite that) who has limited time and money may well confine himself to the monuments of Pharaonic Egypt. For us, handsomely supported as we were and able to take what time we chose, it would have been an insult.

I flew out to Egypt for forty-eight hours to find a boat. In this I was not so much helped as carried by the young Egyptian gentleman, Mr Alaa Swafe, who was to be our Minder. There were very few boats available. The concept of private persons travelling on the Nile in a hired boat and not as one of a tour was, if not new, at least unusual. We searched the waterfront at Cairo with growing despair. I quote from my journal.