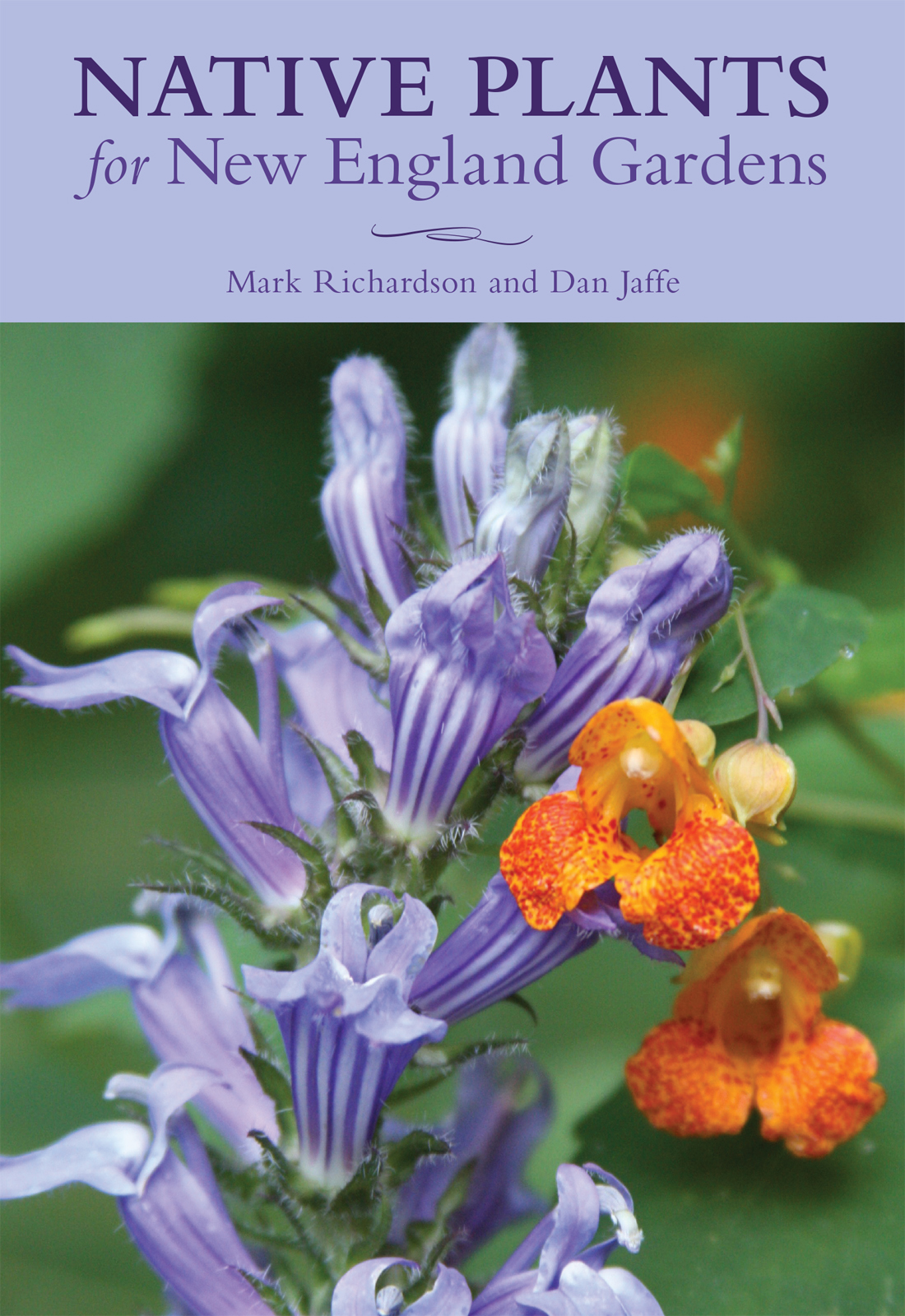

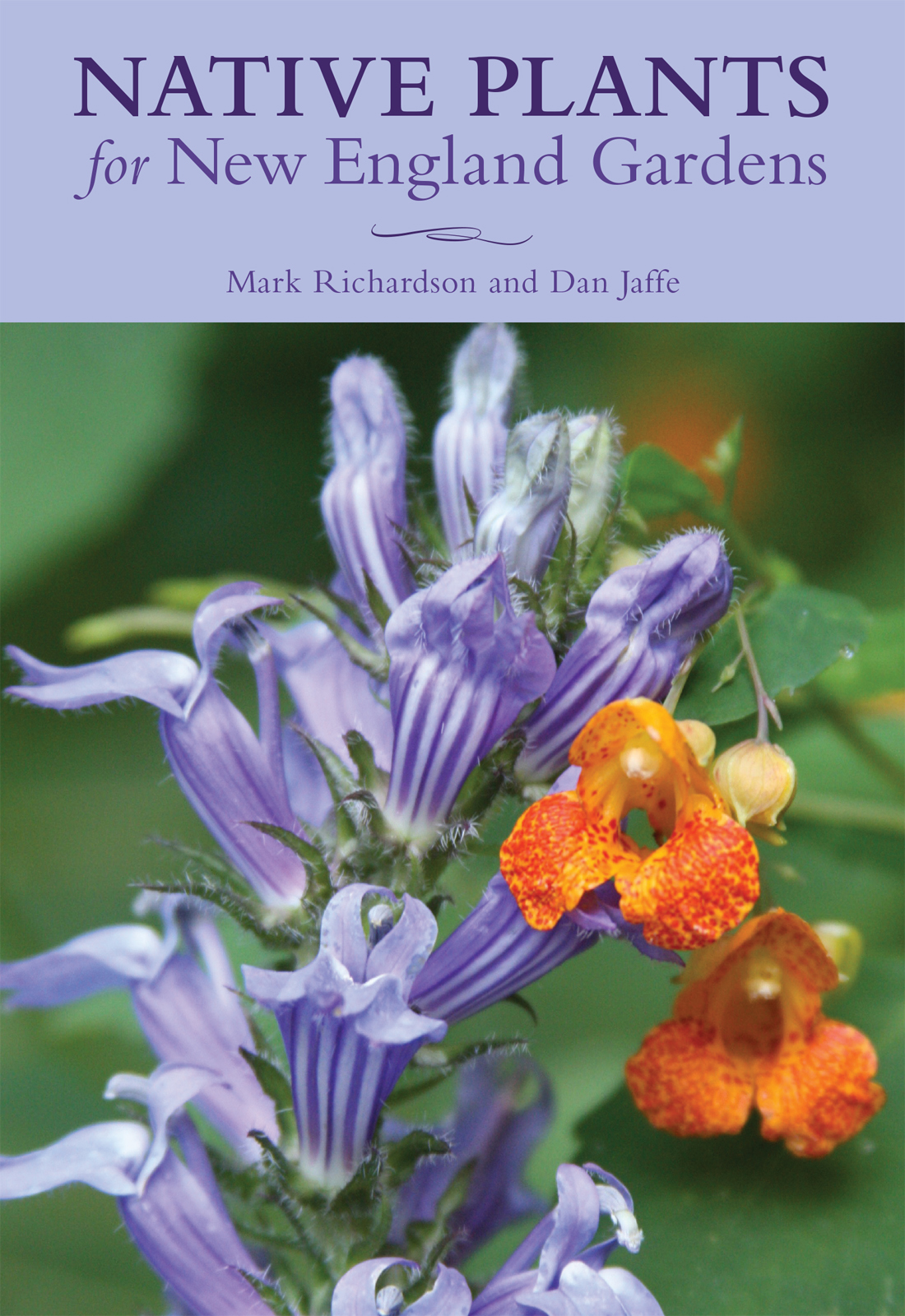

NATIVE PLANTS

for New England Gardens

Globe

Pequot

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2018 Rowman & Littlefield

Photos by Dan Jaffe unless otherwise noted

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Richardson, Mark, 1978-author.

Title: Native plants for New England gardens / Mark Richardson ; photographs by Dan Jaffe.

Description: Guilford, Connecticut : Globe Pequot, [2018] | Includes index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2017035997 (print) | LCCN 2017048678 (ebook) | ISBN 9781493029266 (e-book) | ISBN 9781493029259 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Native plants for cultivationNew England. | Endemic plantsNew England.

Classification: LCC SB439 (ebook) | LCC SB439 .R53 2018 (print) | DDC 635.9/5174dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017035997

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48-1992

Printed in the United States of America

INTRODUCTION

Few things reflect the unique character of New England like its native plants. Native plants not only provide beauty and highlight the distinctiveness of a region, but they also help to support healthy ecosystems, providing habitat for local wildlife. Native plants evolved over millennia within a regions environment, making them well adapted to a particular place, and so when properly sited in a garden, they require fewer inputs like irrigation, fertilizer, and pesticides to remain healthy. As our landscapes become more developed and the space between wild areas grows wider and wider, it is critical that we think of our managed landscapes, like the gardens we all care for, as more than just ornamentation. Our gardens are critical ecosystems, providing habitat for wildlife, capturing and filtering stormwater, and sequestering carbon. Native plants are fundamental components of these urban and suburban ecosystems, and by using more of them in our gardens, we can keep our environment healthy and celebrate the charm of the region we call home, New England.

DEFINING NATIVE

For those of us who work with native plants professionally, defining what we mean by native can be a colossal challenge unto itself. Generally speaking, native is defined by where and when. In other words, native plants are considered to be those that existed in a given location at a specific point in time. The first point, location, is simple enough, but requires that you choose parameters. From broad terms like North American native to narrow terms like native to Middlesex County, Massachusetts, the gardener, landscape designer, or horticulturist sets the criteria and chooses plants that fit. At Garden in the Woods, New England Wild Flower Societys native plant botanic garden in Framingham, Massachusetts, and for the purposes of selecting plants for this book, native plants are those that naturally occur in the US Environmental Protection Agencys (EPA) Ecoregions of New England (see map, Appendix B). According to the EPA, Ecoregions are areas where ecosystems (and the type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources) are generally similar. The original framework for ecoregions was developed by James Omernik in the 1980s. Ecoregions describe large regions that share similar climates, geology, hydrology, and so on. This method for selecting native plants based not on political boundaries (state and county lines, for example), but on ecological boundaries, more closely resembles plant distribution and allows the gardener to choose plants that share similar cultural requirements, having adapted together over millennia.

The second point, when, is a little more complicated and can be a bit more controversial. For simplicitys sake, we define native as dating back to European settlement. In other words, if a plant was in an area at the time the first European settlers arrived, it is considered native. While using a rigid time parameter implies that natural plant migration halted when the pilgrims arrived, it also makes it easy to determine which plants migrated on their own and which were introduced from outside the region. Species migrate constantly; in fact, every plant in our flora migrated northward since the last ice age, a mere ten thousand to twelve thousand years ago. When plants migrate into an area on their own, they do so slowly, typically by natural movement of seed by wind, animals, and water. Natural migration is obstructed by geographic barriers, like oceans and mountain ranges. When people move plants, they can do so across great distances, moving plants across oceans, mountain ranges, and the like. While the vast majority of introduced plants are innocuous and dont ever escape cultivation, there are myriad examples of introduced plants that have escaped cultivation and become invasive.

Invasive species are those that are non-native and whose growth disrupts or causes harm to minimally managed ecosystems. Invasive species are not simply garden thugs that take over a perennial border, like lily-of-the-valley ( Convallaria majalis ); rather, invasive species are those that cause substantial harm to natural lands, like oriental bittersweet ( Celastrus orbiculatus ). Invasive plants are sometimes garden runaways, like burning bush ( Euonymus alatus ), while others were imported for soil stabilization, like kudzu ( Pueraria montana ). Working with native plants is one great way to ensure the plants in your garden will not contribute to the disastrous environmental and economic effects of invasive species, which are estimated to cost the United States over $120 billion annually.

RIGHT PLANT FOR THE RIGHT PLACE

Its easy to get lost in a garden center, admiring the various colors and textures and thinking about where that great new plant with its steel-blue flowers might look best in your garden. Gorgeous plants can be hard to resist. The temptation to buy that attractive new plant without first thinking about whether its compatible with your garden is difficult to avoid. Weve all been there. Wandering through the garden center, your eye is immediately drawn to that shrub with bright red flowers. On the way to the cash register to check out, that tall tree with star-shaped leaves calls out to you. Before you know it, that groundcover with the delicate foliage somehow finds its way into your shopping cart. You get everything home only to realize that all the plants youve just bought want full sun when all you have to offer is shade. Choosing native plants is one easy step toward knowing whether a plant will struggle or thrive in your garden, but its not the only step. Its reasonable to assume a native plant will be hardy enough to survive our winters, and that it is not invasive. Beyond that, gardeners must think about that ever-important principle: the right plant for the right place.

All plants, regardless of their origin, have specific cultural requirements, and if planted in the wrong place will struggle to survive. The key is to visit the garden center armed with a good understanding of what your garden has to offer, and to choose plants based not only on their looks, but also on their cultural needs. Cardinal flower ( Lobelia cardinalis ) is stunning, but plant one in a dry, shady site and it will never flower. On the other hand, plant bearberry ( Arctostaphylos uva-ursi ) in a wet spot and it will rot. When selecting plants for gardens, the goal should be to put plants where they will require no supplemental irrigation once established (a period of two to three years, depending on the plant and the situation). To understand what your garden has to offer, consider three important factors: light, soil type/moisture, and space availability.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48-1992