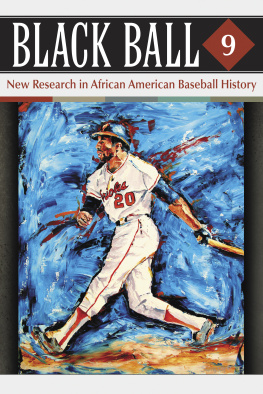

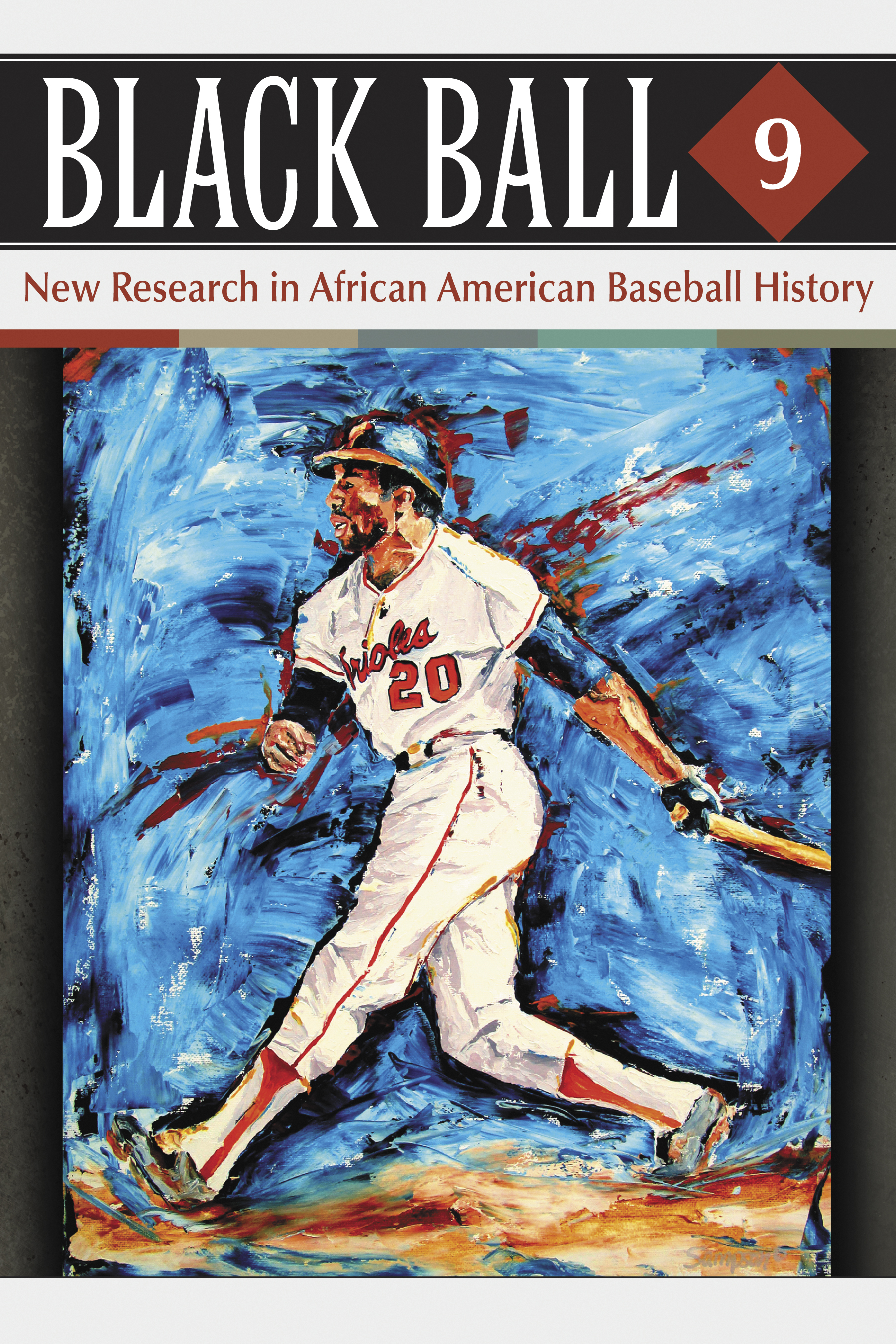

Black Ball 9

New Research in African American Baseball History

Edited by

Leslie A. Heaphy

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

Back issue requests to McFarland by mail at Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640, by phone at 800-253-2187, by fax at 336-246-5018, or online at www.mcfarlandpub.com

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2334-4

2017 McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

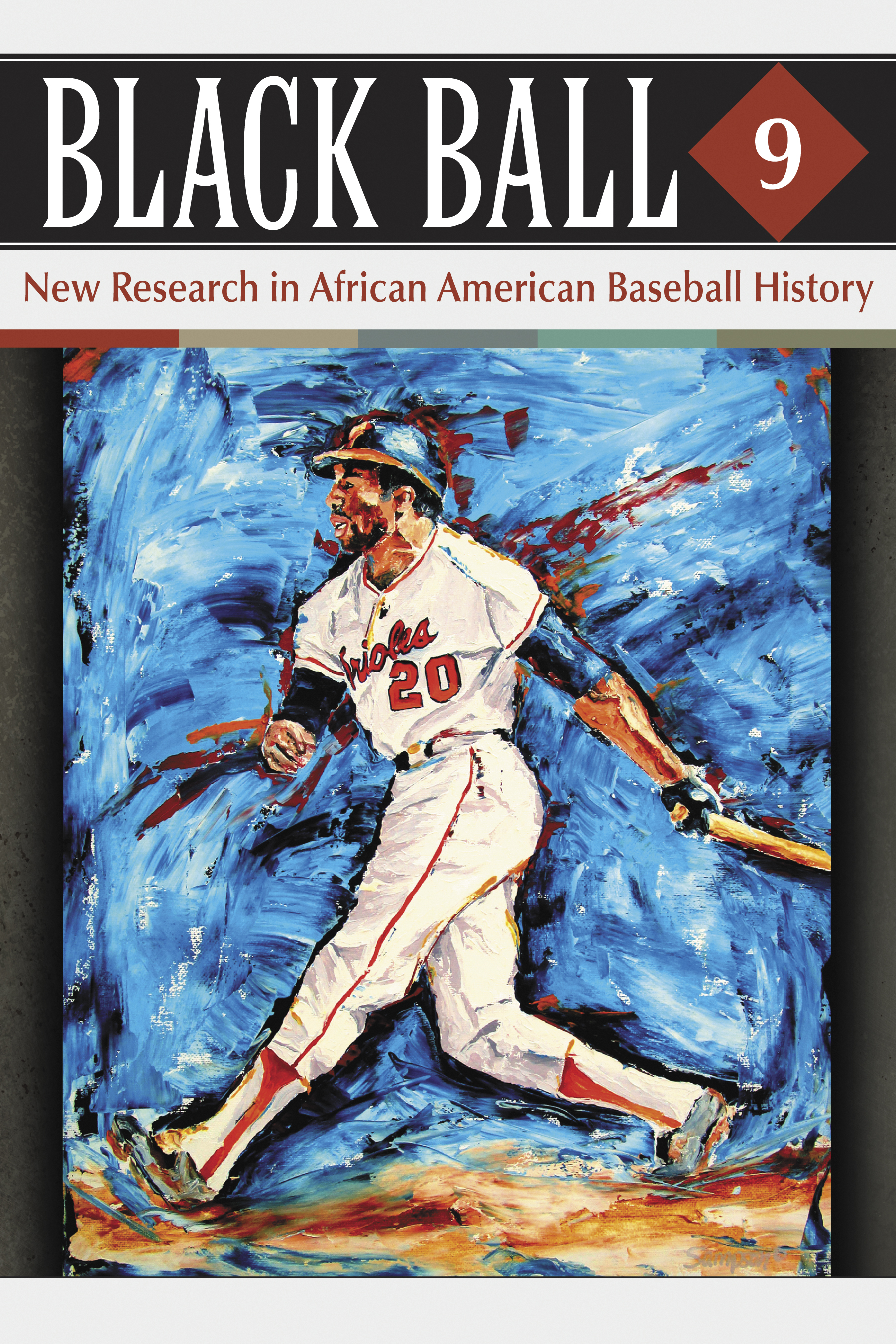

Frank Robinson by Debbie Sampson, oil on canvas, 16" 20", 2016.

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Editors Note

THE 2016 MAJOR LEAGUE SEASON ENDED with an event 108 years in the making. And that seven-game World Series, in which the Cubs downed the Indians to stand atop the big leagues for the first time in more than a century, was one of the most exciting in recent memory. While I am happy for the Cubs fans, who finally saw their team win, it seemed a little unjust that either team should have to lose. The Indians had themselves gone 68 years without a Series title, and the momentum changes throughout the series seemed like something, to quote Bart Giamatti, designed to break your heart, no matter the side you were on. So lets hope Indians fans soon see a celebration like the one we saw last November 2 on the North Side of Chicago. (Oh, and maybe hope, too, that my Mets will redeem themselves after losing to the Giants in the National League Wild Card Game.)

Another way of looking at that historic match-up last fall? It was the first time the Cubs had seen the World Series since Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. And for the Indians, it was as close as they had come to winning it all (perhaps along with their seven-game loss in 1997) since 1948, when Robinsons AL counterpart, Larry Doby, and the ageless Satchel Paige helped Cleveland to the championship.

This volume represents something noteworthy for Black Ball, too: After nine years (eight volumes) as a journal, it marks our first as an annual book. Apart from a few design changes, longtime readers may see little difference between old and new, but McFarland hopes that by better engaging its book-oriented production, sales, and marketing expertise, Black Ball will have a higher profile and reach a larger readership.

The articles included in this volume are as varied and interesting as ever. Among the first-time contributors to Black Ball is Zach Moser, who provides a fresh perspective on a familiar topic: Cap Ansons role in the segregation of baseball in the nineteenth century. Joining Moser among the first-timers is Tyler Evans, who explores the importance of Buck ONeil to his adopted home, Kansas City, detailing ONeils off-the-field contributions, which are lesser known than his on-field achievements. Also new to Black Ball is author Doug Branson, who recently published a book on the career of Larry Doby. In his article, Branson argues that Doby has lived too long in the shadow of others, even Robinson, and that its time to give him his due. Playwright Ruby Berryman takes an original approach to the long, peripatetic career of Satchel Paige, describing its parallels to the monomyth, or heros journey. She has even created her own visual representation of this journey which she highlights in her article. Doron Goldman also focuses on one of the players who helped integrate the majors, examining the early career of Monte Irvin. Goldman adds dimension to our portrait of the Hall of Famer by highlighting the lesser-known aspects of Irvins life. Finally, Keith Wood chronicles the rise of Dr. J.B. Martin, owner of the Memphis Red Sox and later the president of the Negro American League. Part of the story that Wood focuses on is the strained relationship between Martin and E.H. Boss Crump, who ruled Memphis politics.

Each of these articles adds in some meaningful way to the existing literature on the Negro Leagues. I learned a great deal, even about the topics that researchers have returned to time and again. I hope you will find these articles as enlightening, and even inspiring, as I did. What they demonstrate is that if the decades of research into the Negro Leagues have laid bare the contours of its history, there is still much that we can do to add texture and nuance to the picture now emerging.

Leslie Heaphy

Barnstorming as Theatre

Satchel Seizes the Elixir

RUBY C. BERRYMAN

This article places the life of baseball great Satchel Paige on the timeline of the myth structure of the theatre. It examines Satchel Paiges baseball journey through the Negro and Major Leagues, from his response to the initial call to adventure where he learned the game to his return with the elixir of Major League baseballs blessing. Satchels life moved from the ordinary continuum of its dramatic structure to the extraordinary timeline of myth structure. His dramatic manipulations on the baseball diamond created a meta-theatrical world that alleviated tensions in racially divided venues, heightened interest in the game and allowed himself and his Black teammates to continue to play the game they loved. By doing so, the journey continued and Satchel was able to stay on the path to greater glory. This article shows how, through this decades long dramatic process, Satchel arrives at the heros destination: the baseball Hall of Fame. Thus the new equilibrium of myth structure was established, and it gave future Negro players the ability to look forward to having their own call to adventure in the words, Play ball!

THIS ARTICLE AIMS TO SHOW how the life of baseball great Leroy Satchel Paiges life embodies the classic myth structure of storytelling. Myth structure has been used from the beginning of the first etchings on cave walls to the current storytelling channels of theatre, television, film, gaming, and social media. The simple, but potent, underlying form for all these mediums is the monomyth, Baseball lends itself to myth structure, as both have the same core objective and process for obtaining it. The objective is to journey away from home, then return with something of value to share with the whole community. A home run (or any run for that matter), RBIs and certainly a win benefits the whole tribe. As the hero travels through the mythical process, he experiences the rites of passage that Campbell describes: separation (from home)initiation (into the game by getting on first base)the return (back to home). Vogler confirms that:

Baseball can be read as another metaphor of life, with the base runner as the hero making his way around the stages of the journey. [When I] drew the heros goals in each movement as straight lines, vectors of intention rather than curves. I was amused to realize I had just drawn a baseball diamond (in reverse) Ive often felt the layout of game-playing fields produces patterns that overlap with the design of the Heros Journey.

By placing Satchels heros journey on a baseball diamond of myth structure, one can observe how he traveled from his Ordinary World through the Special World of baseball and home again. Satchel once quipped about himself that, the only change is that baseball has turned Paige from a second class citizen to a second class immortal. Satchels journey toward immortality plays out on the baseball diamond during a time in our nations history that was so segregated it garnered a proper name: Jim Crow, and would be the greatest foe of his time and that of all American blacks of that era. Many fight this great enemy with pen, sword, and sermon. Satchel will use a baseball. However, to beat Jim Crow, Satchel must depend not only on his game-winning pitching, but also on his dramatic manipulation of the spectators as he becomes a performer while maintaining his focus as gladiator. In his meta-theatrical world, simultaneous dramas play out between the lines of the baseball diamond and off the field as his athleticism constantly demands a review of the color line in baseball and Jim Crow in America. The worst time is the greatest moment for a legend to be born and when Satchel Paige accepts the call and goes on the Heros Journey, he clears the way for young black boys through the ages to dream of their own Call to Adventure in the words: Play ball!

Next page