Introduction

Graced by Grete

By David Willey, Editor-in-Chief, Runners World

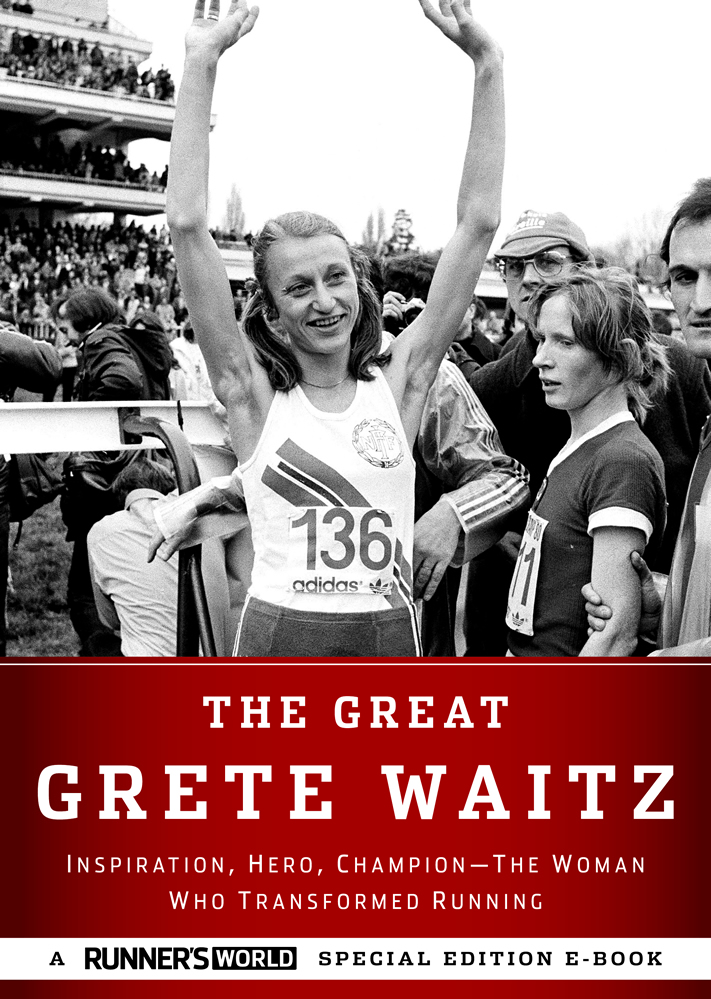

It can be unnerving to meet someone famous for the first time, especially someone youve admired for decades, someone who ran so fast but with such Zen-like, expressionless gracea Mona Lisa in pigtailsthat she made you, for the first time, want to run like a girl. But Grete Waitz always hated being famous, so when I introduced myself at our Heroes of Running awards in New York City in 2005, it wasnt the world-beating First Lady of the Marathon who shook my hand but the former schoolteacher who once declined an endorsement deal from a dairy because she didnt like milk. She wasGrete. Heroic and humble all at once.

We were honoring her with a Lifetime Achievement award, in recognition of her record- and boundary-breaking career: nine wins in New York; 19 world bests (road, track, and cross-country); the first woman to break 2:30 in the marathon. No one did more to inspire runners or transform our sport into what it is today.

We asked Deena Kastor, who, running in Gretes footsteps, had won Olympic bronze in the marathon the previous summer, to present her with the Heroes award. Grete had recently been diagnosed with cancer, and after Deenas remarks, there wasnt a dry eye in the house. When Grete came up to accept the award, she had cried the contact lenses out of her eyes. I told myself I wouldnt cry, she said a few moments later, but I cant hold my tears back. But they are happy tears.

And they were. The way she handled her cancer over the next six years proved it. She stayed active and encouraged others to do the same. She helped start a cancer-support foundation in her home country of Norway called Aktiv mot kreft (Active Against Cancer). And in this technology- and media-saturated age when we often know what our heroes and leaders had for breakfast (whether we want to know or not), Grete took a dignified approach, keeping the nature of her disease private and never letting it define her or transform her into a victim. She died in April, 2011, at age 57, but up until the end, hers was a life well-lived.

To remember and commemorate Gretes importance, weve assembled this special-edition e-book, The Great Grete Waitz, a compilation of the best stories about her from the Runners World archives. The entries date back to Grete, Amby Burfoots definitive profile from 1981, and include The Race of a Lifetime, which recounts the New York City Marathon Grete ran with Fred Lebow in 1992, two years before the race cofounder died of cancer, as well as From Out of Norway, Executive Editor Charles Butlers recent account of Gretes astonishing New York City Marathon debut in 1978.

For his piece, Butler took the oral history approach because, as many journalists can attest, quotes from Grete herself were few and far between. Im not very outspoken, she told RWs Dave Prokop in 1984. Im a very, very normal person. I just happen to run fast. So Butler brought Grete into full focus through the eyes of the people who knew her best. His first call was to Jack Waitz, Gretes husband of 36 years, who then connected him with Gretes brothers and former coaches. In all, Butler interviewed dozens of friends, family members, and rivals, uncovering new facts and anecdotes. As youll discover in his story, Grete entered late, on a lark, and ran in obscurity, wearing a hand-drawn 1173 bib number. But the race changed everythingfor her, for Jack, for all of us.

I hope you enjoy rereading these stories as much as I have. Incidentally, a portion of the books proceeds will go to Aktiv mot kreft. Its a small gesture with a simple message: Thank you, Grete.

Grete

By Amby Burfoot

Oslo provides the setting for the ultimate story of the worlds greatest female distance runner.

March 1981

A mile from downtown Oslo, Norway, I am runningor more accurately, slipping and slidingthrough Frogner Park, a favorite recreational ground of many Oslovians. This mid-December day is a complete gray-out. A steady snow falls and is turned immediately to slush by the unusually warm, 35-degree temperature. Even at my sightseers pace, about eight minutes per mile, I can barely stay on my feet, and I fall once on the slick pavement.

Oslo in winter is not terribly hospitable to the runner. The land of the midnight sun becomes the land of the midafternoon night. The sun rises at 8 a.m., sets at 3 p.m., and its rays are sickly and slanted. Even with a boost from the Gulf Stream, winter temperatures average about 20 degrees. The cover of snow grows deeper and deeper from November through March. For anyone, life is an effort; for the runner, life is a struggle.

Frogner Park provides ironic amplification of this point. It is Oslos best winter running area with walkways that are flat, straight, plowed, lighted, and 600 yards long. But to run in Frogner Park is to encounter the sculptures of Gustav Vigelandall 190 of themin granite, iron, and bronze, the result of a unique contract between Vigeland and the city of Oslo, signed in February 1921. Vigeland agreed to give the city all his works, past and future, in return for parkland in which to display them, a studio apartment, and all the supplies and assistants he would need. The theme of Vigelands sculptures is the struggle of life; it is embodied by his crowning achievement, The Monolith, a 60-foot-tall spire composed of the writhing figures of 121 men, women, and children. To run in Frogner Park is to sense the struggle and share in it.

As I jog out of Frogner Park, I pass a small childrens playground packed with 3- and 4-year-olds dressed in brightly colored snowsuits with contrasting mittens. They are on swings, pushing carriages, and sledding down a short incline on red plastic discs.

The children are representative of Norways outdoors people. A 1973 survey found that 42 percent of Norwegians train regularly for some sport while 65 percent consider themselves physically active. On a typical winter weekend, somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000 (out of a total of 460,000) of Oslos citizens ski in the forests surrounding their homes. In the summer as many as 15,000 Norwegians enter marches (walking contests) that cover up to 60 miles in a two-day period. They camp overnight on the hillsides, taking advantage of Norwegian law, which allows access to all.

The entire country1,100 miles long, only four miles wide at its narrowest point, including more than 150,000 islands, and with the lowest population density in continental Europebelongs to all Norwegians. Maintaining the land for recreational purposes is very, very important, said Arne Kvalheim, a former 3:56-plus miler who graduated from the University of Oregon in 1970 with a bachelors degree in political science and has been a full-time Oslo city councilor the past five years. Id say its one of the few things in life thats sacred to me.

Six hours after my first run through Frogner Park, I am headed there again, this time in a tan 1978 Peugeot sedan driven by Grete Waitz. After three years of getting used to the sound of the name (pronounced whites), the mind still boggles at the unparalleled running accomplishments. Three marathons. Three world records. Her present best time of 2:25:41 is almost nine minutes faster than the record stood before October 22, 1978, the day of her first New York City race. At that time people were saying the womens world record progression would have to slow because, after all, it had dropped so precipitously in reaching the mid-2:30s.