The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Dedicated to my mother,

Renee Miller,

who seldom told me

to get my nose out of a book

Foreword

When a young man, John Muir crafted intricate clocks and other clever devices from wood, and once even invented machinery to mass-produce rake and broom handles. But, a Muir legend claims, this gifted woodworker so loved trees that he could not himself cut into a living one.

While there must have been occasions when he had to chop down a tree, each time he did so he probably first gritted his teeth and apologized to God. A great mission of his life, after all, was to see to it that there were more live trees than dead ones to serve mankind, and to this end he influenced four United States presidents to think of living trees. Benjamin Harrison preserved 13 million acres; in 1897, Grover Cleveland set aside 21 million acres of sheltered forest lands; William McKinley contributed several million more; and Theodore Roosevelt signed bills to protect 148 million acres of forested wilderness.

(Muir even loved trees that had turned to stone and in 1906, owing largely to his influence, his friend President Roosevelt designated Arizonas Petrified Forest a national monument.)

Everything in nature seemed to fascinate him, boy and man, Rod Miller says of this valiant conservationist, and indeed, from his boyhood days on the wild and foggy North Sea coast of Scotland to his death in 1914, Muir saw a spirit-rejuvenating quality in the inventions of God. By this he meant all the inventions: Trees were a passion but he loved all plants, all animals, birds, fish, and insects, rivers, mountains, canyons, deserts, glaciersevery creature and feature of Mother Earthand he stood in awe and wrote poetically of rain, snow, wind, lightning, earthquake, avalanche, and all the grand, terrifying, and inexplicable forces of nature.

Nothing thrilled him more than witnessing, as he often did in his Alaskan journeys, a glacier violently birthing icebergs, or finding a rare flower, or standing alone and silently on a Sierra peak gazing at a valley below. He thus learned the redemptive value of the wilderness but not from armchair musings or deep readings in philosophy. He was invigorated by the natural world by traveling it, mostly on foot, a knapsack on his back, sleeping under the stars.

* * *

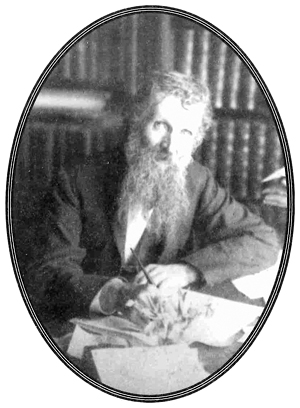

The romantic images of himas the sinewy man of the mountains with the flowing Old Testament beard, or the magnificent tramp walking a thousand miles from Kentucky to the Gulf Coast of Florida, or brewing tea in the High Sierras while studying a plant specimen with a magnifying glassare faithful concepts. But in this eloquent book, Rod Miller has ensured that we see all the other John Muirs, all of them fascinating.

There is the Muir who once said, No truant schoolboy is more free and disengaged from all the grave plans and purposes of ordinary orthodox life than is me, but who, because of the grave plans and purposes of others, was forced into the uncomfortable role of combatant. As he rose from obscurity to become a voice for the preservation of the wilderness, he had campaigns to wage, people to convince, and had to engage in national debates, often acrimonious, with politicians and industrialists. One of his finest, final, battleswhich he lostwas for the preservation of the Hetch Hetchy Valley, second only to Muirs beloved Yosemite in pristine beauty, against efforts to submerge it under a reservoir to supply water for San Francisco.

There is Muir the scientist, whose explorations of the Yosemite Valley, his uncanny ability to read the runes of canyon walls, convinced him that the valley was formed by glacial action and not by sudden cataclysmic upheaval, the theory accepted by the scientific establishment. For this idea, one opposing scientist called him an ignorant shepherd, but the shepherd was anything but ignorant and his idea prevailed.

There is Muir the reluctant author who found writing painful and a poor vehicle for describing real experience, but who wrote profoundly and poetically in ten books and in the nations most influential magazines and newspapers.

There is Muir the private, reclusive man who avoided crowds, speechmaking, and the public spotlight, yet who organized the powerful Sierra Club in 1892 and served as its founding president, and who became the father of the National Park System. (Only Yellowstone preceded his efforts.)

And there is Muir the lucky husband, married to an extraordinary woman who gave him two loving daughters and who encouraged his roamings, enabling him to declare his cosmic citizenship, his freedom to wander, and to identify himself as John Muir, Earth-planet, Universe.

* * *

Ralph Waldo Emerson kept a list of men who had influenced his life, a list that included the name John Muir. The two met only once, when Emerson visited Yosemite in 1871 with Muir as his guide, but corresponded until the New Englander died in 1882.

What did this sheltered philosopher and poetic genius see in the untamed, idealistic man of the mountains that was so influential? Emerson did not elaborate, but a safe answer is that he admired Muirs daring, courage, nobility of character, and his selflessnessall the essentials of heroism.

D ALE L. W ALKER

A Place in History

If American history were a bookshelf, the story of John Muirs productive life would tuck conveniently between the volumes on the Civil War and World War I.

He left home for his first trip of any significance as an independent adult in the fall of 1860 to exhibit his handcrafted wooden clocks and other inventions at the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society Fair in Madison. Within months of his departure, the Republican candidate for president, Abraham Lincoln, won election and Southern secessionists pulled the trigger on the Civil War.

Largely silent on the subject of the war years, Muir spent them as a student at the University of Wisconsin or tramping about and working in Canada. One of his younger brothers fled to Canada to dodge the military drafts sweeping Wisconsin, since the family lacked the means to buy a deferment or pay for a substitutethe customary means of draft avoidance at the time. Muir later followed him across the border, where he spent his time hiking and camping, identifying and studying plants in the forests near the Great Lakes. He later joined his brother and the pair worked together in a Canadian sawmill and wood products factory as they awaited the wars conclusion.

By todays standards, Muirs avoidance of military service might be judged a cowardly or unpatriotic act; at the time, however, it was neither unusual nor even necessarily frowned upon. The draft was unpopular and draft riots were widespread, and circumventing conscription, by legal means or otherwise, was commonplace. Moreover, service may not have been required of Muir as he was not a citizen of the United Stateshe did not apply for formal citizenship until many years later when, at age sixty-five, he needed a passport to travel outside the country. In any event, his name was never drawn for conscription.