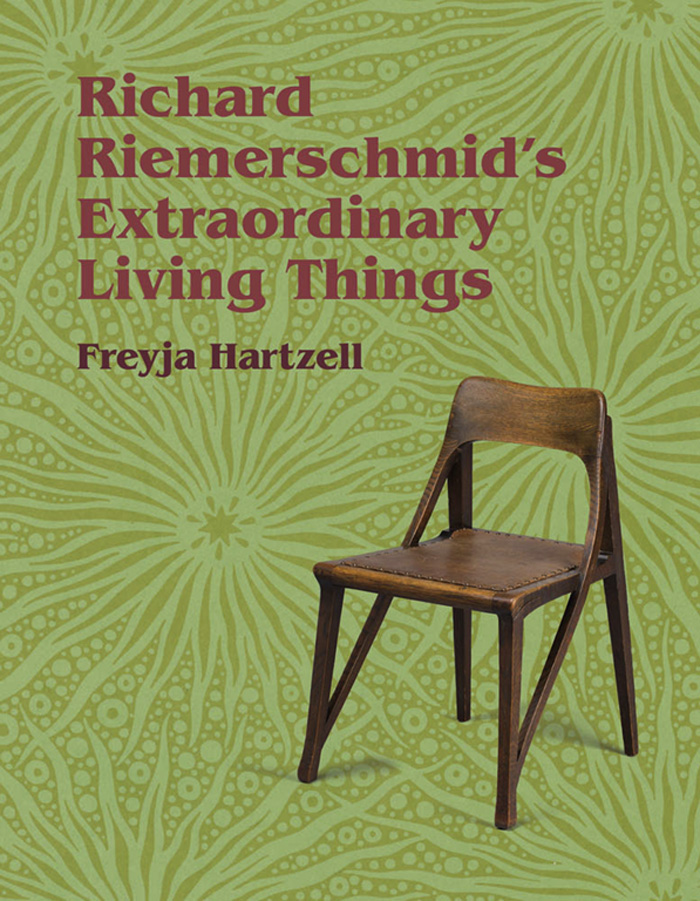

Richard Riemerschmids Extraordinary Living Things

Richard Riemerschmids Extraordinary Living Things

Freyja Hartzell

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

Published with assistance from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in Arnhem Pro and Frank New by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hartzell, Freyja Thorbjrn, author.

Title: Richard Riemerschmids extraordinary living things / Freyja Hartzell.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021049761 | ISBN 9780262047425 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Riemerschmid, Richard, 1868-1957Criticism and interpretation.

Classification: LCC NK1450.Z9 R5434 2022 | DDC 745.4dc23/eng/20220423

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021049761

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r0

For Sally and Jon

... with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.

William Wordsworth

Contents

Introduction

Extraordinary Living Things

It speaks, it talks in forms, it makes its personality visible.

Hermann Obrist

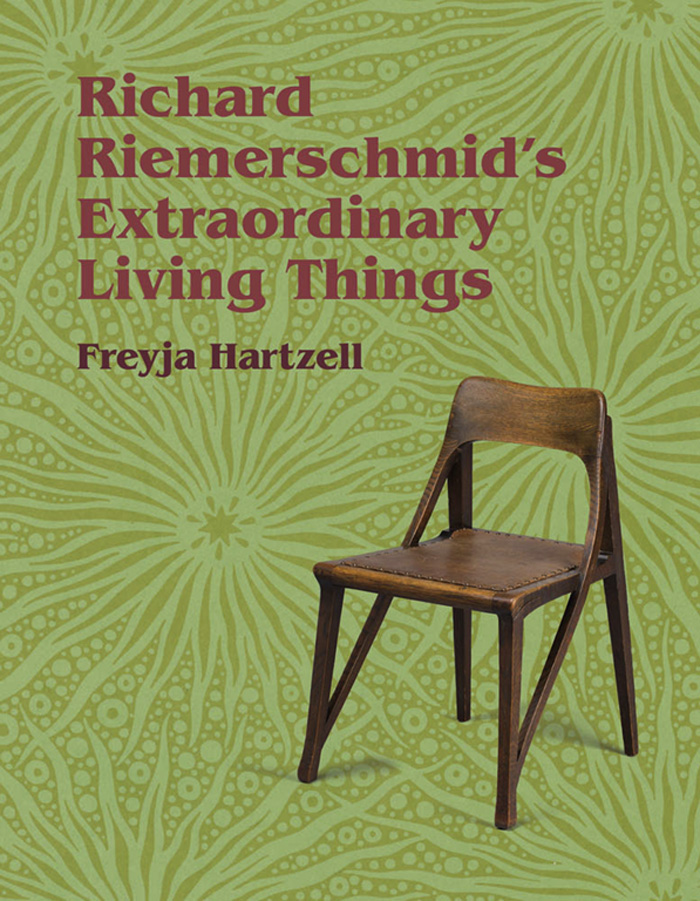

Munich sparkled, wrote Thomas Mann in 1902 of the Bavarian city he called home. And as Munich sparkled, Manns desk chair trembled (figure 0.1). Perhaps it trembled vicariously with the writers nerves; perhaps it trembled momentously on the brink of the modern century; or perhaps it trembled simply with joythat irrational, animal joy of the organism coursing with lifethe sheer joy of being alive. Or did it really tremble at all? Surely it seems unlikely that any chair should tremble, and especially that this small, unassuming, cherrywood desk chair would comport itself so shamelessly. So we look again. Yes, it still trembles. While its squared, splayed feet root it to the ground, and its generous seat and broadly curving backrest invite the writers body, the limbs that connect themthe slender legs and supple armscannot keep still.

Figure 0.1

Richard Riemerschmid, Desk Chair, designed 1898 (this example purchased by Thomas Mann 1902). 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Manns unruly desk chair was designed by his Munich compatriot, the artist, architect, and designer Richard Riemerschmid (18681957). It may come as something of a surprise, then, that when Riemerschmids name appears within the canon of modern design, it is often accompanied by words such as standardization, practicality, or Sachlichkeitthat core tenet of German modernism, typically rendered as objectivity in English. In fact, surveys of design history tend to hail Riemerschmid as a pioneer of functionalism. Riemerschmid has been understood as a transitional figure, conveniently bridging a stylistic gap between 1890s Art Nouveau and 1920s modernism. Unparalleled in their own time, Riemerschmids things are repeatedly seen as ahead of that time. And so they are valued for their anticipation of the better-known industrial design of the Bauhaus school, celebrated in twentieth-century design scholarship for its dissemination of a functional, reductive design aesthetic in postwar Europe, Britain, and the United States through products that have since become synonymous with the words modern design.

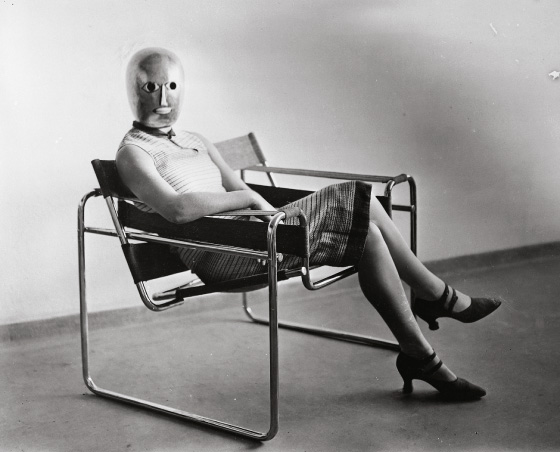

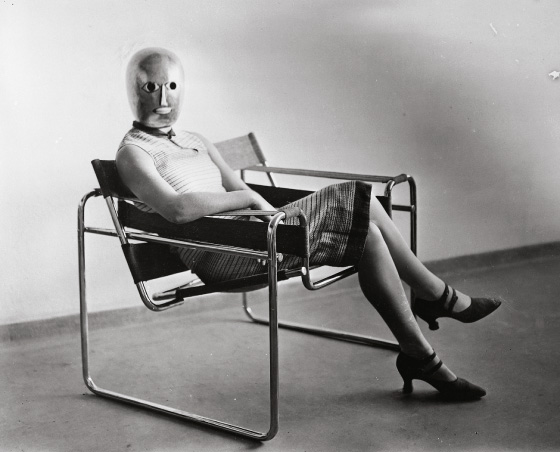

So perhaps Thomas Manns cherry chair trembled toward something; perhaps it shook in anticipation of its own future perfectionof a more definitively modern chair. Certainly, Bauhaus designer Marcel Breuers B3 club chair, designed in 1925 and known by its affectionate nickname Wassily (for Wassily Kandinsky, Breuers Bauhaus colleague at the time), has been seen as such a chair (figure 0.2). Design theorist Frederic J. Schwartz has written that Breuers now iconic tubular steel and black canvas chair distilled thousands of years of design into a few spare lines and was, in this sense, the final iteration of the image chair. And the forms of these two artists chairsManns and Kandinskysdo present both resemblance and evolution through their similarly sparse designs, their equally accommodating seats and embracing backrests, the upward springing of their legs, the lilting lines of their arms: Breuers canvas flexible by nature, Riemerschmids wood made so through design.

Figure 0.2

Erich Consemller, Untitled (Lis Beyer or Ise Gropius wearing mask by Oskar Schlemmer in Breuers Wassily chair), 1926. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin / Stephan Consemller.

But the Wassily chairs evolution also held a threat for the trembling Munich desk chair, and for all chairsfor the very presence of the chair as a concrete thing. For, as Schwartz has noted, Breuers tubular steel and fabric chair automatically reduced its material to a collection of abstract, floating lines and planes; even the reflections on the chromed surfaces, Schwartz observes, narrow the cylinders of steel into thin strokes of an imaginary pen. And so the most interesting image of this final iteration of the image chair features not Wassilys abstract geometry but a mysterious, masked sitter. With the Wassily chair, then, the dialectic of dwelling had come to a standstillor, in more comfortable terms, to a seat. In 1925, the human subject was framed by the subservient, inanimate object. But in 1902, Riemerschmids obstreperous armchair was yet in motionacting out. It contested the sitters claim to subjecthood. Rather than dematerializing, it asserted its materiality, shaking and destabilizing the very relation of subject to object. While Breuers chair may look more modern in the teleological terms of stylistic evolution, it is Riemerschmids chair that embodies the complexity of the conflicted modern self.

We can draw an even closer comparison between Breuers 1928 B32 side chair (figure 0.3) and Riemerschmids 1905 machine chair (figure 0.4). Both chairs are reduced in design, employ traditional caned seats, and were produced in multiples; Breuers chair was mass-produced by the Thonet bentwood and tubular steel manufacturers, and Riemerschmids was serially produced at the Dresden Workshops. An example of Riemerschmids bare-bones machine chair in the collection of Berlins Bauhaus Archive perpetuates the notion of Riemerschmids supporting role in a modernism destined for the Bauhaus. The chairs remarkably spare form, its lack of ornament, and its straightforward construction from standardized, serially produced parts fabricated with the aid of machines seem to herald the advent of what has since been termed Sachlichkeit

Next page