Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

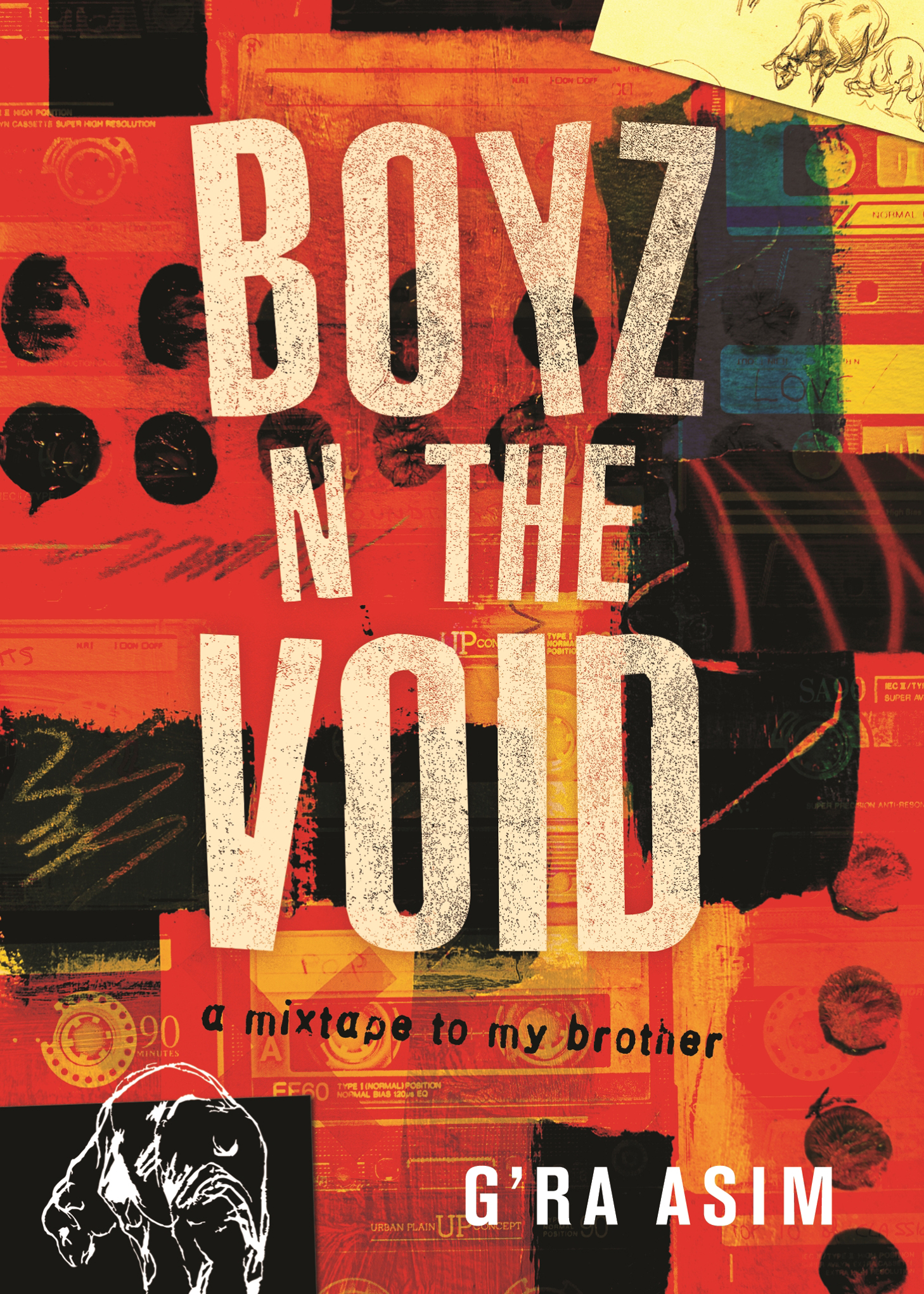

For the Asim team

To understand that you are black in a society where black is an extreme liability is one thing, but to understand that it is the society that is lacking and impossibly deformed, and not yourself, isolates you even more.

AMIRI BARAKA

Introduction

T heres a sullen and brooding six foot two, 240-pound presence in my parents house, and his shadow looms large over the otherwise placid nest. The presence is among the most timeless of American bogeymena black male in a state of rapid physical maturation. My folks regard the presence in a fashion that is heritage in their country of origin, which is to say, the presence is making them nervous. Having already reared three boys and one girl to satisfactory adulthood, my folks fancy their home as a factory of black excellence, and the lone remaining straggler on their well-trodden conveyor belt defies the troubleshooting best practices theyve developed over thirty-four years on the job. My youngest brother, Gyasi, is a capable but disinterested student. Where other teenage boys chase girls and alcohol, Gyasi predominantly lurks indoors like some Wi-Fiempowered Boo Radley. His communication with my parents is minimal, and when he does deign to acknowledge them, he alternates between withering sarcasm and charged silence. Gyasi teases my parents with glimpses of his intellectual and artistic potential but is recalcitrant when pushed to put his talents to use. Fourteen years apart in age, he and I are respectively the second- and fifth-born children of five and have always enjoyed a strong rapport, but even I have been of marginal help in allaying his malaise.

The familiar chorus of my mothers vexation is Im worried hell be living in my house until hes forty. In fairness, it was not long ago that my mother fretted over a similar prognosis about me. I, too, was an academically withdrawn malcontent with an allergy to authority. My angst was both formless and easy to explain. I dont presume that Gyasi and I are exactly the same per se, but I can imagine he might be suffering from a crisis similar to the one that afflicted me as a teenager: an inability to envision a future in which a person such as he can fit comfortably into a ruthlessly competitive, anti-intellectual, anti-black society.

He could not be blamed for sensing the jarring discontinuity between the climate beyond his front door and the one in which he has been carefully incubated. Our father is an author and writing professor and our mother is a playwright, actor, and homemaker. Being raised by artists has not only shaped my and Gyasis aesthetic leanings but also framed our perceptions of the American story. Our parents, both products of inner-city St. Louis, dropped out of Northwestern University in the late 1980s to return to the ghetto to raise my eldest brother and me. When not evading gunfire, Mom and Baba wrote and produced plays, organized poetry readings, and published literary magazines with their young sons playing at their feet. Our household was a fecund micro-bohemia situated incongruously within a warzone. As my parents creative triumphs accumulated, our circumstances improved enough to move to the comparatively posh suburbs of Silver Spring, Maryland. Gyasi was born there. Hes in some ways a beneficiary of a middle-class upbringing but is acutely aware of the Herculean feats it took for our family to produce such an environment and the precarity of sustaining it. After the economic downturn of the late aughts, our family relocated from Silver Spring to urban Baltimore. Gyasi briefly attended a public elementary school there until my parents grew so frustrated with the threadbare curriculum that they pulled him out in favor of homeschooling.

For the Asim children, living at the mercy of the economic peaks and valleys of my folks artistic lives yielded a kaleidoscopic view of excess and indigence, oppression and opportunity. As a result, a grasp of heterogeneity is seared into all of our makeups. Gyasi and I, especially, are native dwellers of liminal space, and our experiences have often involved the exposure of unlikely confluences between distinct traditions, cultures, or ideologies.

My youngest brother and I lean on each other as intellectual sparring partners, creative collaborators, and confidants. We cant really afford not to. Were a generation apart but identify more with one another than anyone in either of our respective peer groups. The Asims are not unlike a twenty-first-century edition of J. D. Salingers Glass family. Like the clan that starred in Nine Stories and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters, were a close-knit but contentious family of bookish eccentrics struggling to reconcile our bohemian sensibilities with the prevailing norms of our era. My mothers unease about Gyasis prospects for assimilation recalls Bessie Glasss concern for her youngest daughter in Franny and Zooey. When I reflected on Gyasis coming of age, I thought of the Glasses parallels and noted how the critical intervention of Frannys like-minded older brothers helps Franny to recover from an existential breakdown. In the books conclusion, Zooey comforts Franny by explaining that even if no one around her appreciates her attempts to defy the insensitivity and superficiality of 1950s Connecticut, Jesus notices, and she must continue to lead a virtuous life to maintain the smile on His holy countenance.

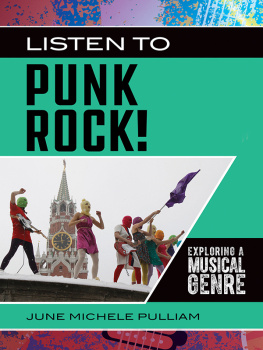

Cue record scratch. Thats not the kind of sentiment likely to galvanize my stringently empiricist baby brother. So what might our own version of the game-changing sibling-to-sibling pep talk look like? Even our parents seem to underestimate the vastness of the chasm between the value system of the house we grew up in and the broader culture in which we reside. Navigating that divide is no small task, but punk rock has been my unlikely lodestar.

I am not compiling a mixtape for the sake of indoctrinating my brother, of turning him into my mohawked spitting image. Im making the mixtape because punk is fun, because a robust engagement with counterculture can serve as a vital antidote to soul-sucking normalcy, because remembering that you have predecessors who wrestled with many of the same riddles that you may wrestle with can help you feel that a roadmap to self-actualization exists. The result is part Nick Hornsby, part Ntozake Shange: my All-Time, Top-10 Angst-Neutralizing Punk Songs Because the Rainbow Clearly Isnt Enuf, Bruh.

Africa Has No History

An Annotation of Anti-Flags A Start

Subject: The History of White People

Africa is not an historical continent; it shows neither change nor development, and whatever may have happened there belongs to the world of Asia and of Europe.... Nothing remotely human is to be found in the African character... their condition is capable of neither development nor education. As we see them today so they have always been.

GEORG WILHELM HEGEL ,

German philosopher, 1854

At present there is no African history: there is only history of the Europeans in Africa, the rest is darkness... and darkness is not a subject of history. Please do not misunderstand me. I do not deny that men existed even in dark countries and dark centuries, nor that they had political life and culture, and purposive movement too. It is not a mere phantasmagoria of changing shapes and costumes, of battles and conquests, dynasties and usurpations, social forms and social disintegration. If all history is equal, as some now believe, there is no reason why we should study one section of it rather than another; for certainly we cannot study it all. Then indeed we may neglect our own history and amuse ourselves with the unrewarding gyrations of barbarous tribes in picturesque but irrelevant corners of the globe: tribes whose chief function in history, in my opinion, is to show to the present an image of the past from which, by history, it has escaped.