VII: RICHARD J. EVANS Europe 18151914

TIM BLANNING

The Pursuit of Glory

Europe 16481815

VIKING

ISBN: 978-1-1012-0245-6

Copyright Tim Blanning, 2007

For Nicky, Tom, Lucy and Molly

List of Illustrations

Copy to follow

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Copy to follow

List of Tables

Table 1. Travel times from London 17001800

Table 2. Population of European countries 16501800

Table 3. Population of Europe

Table 4. Changes in Dutch urban population 16881815

Table 5. Total Russian foreign trade

Table 6. Increases in Bohemian textile-spinner numbers during the 1760s and 1770s

Table 7. Family average annual expenditure c. 1750

Table 8. European army numbers 16301786

Table 9. Army numbers during the eighteenth century

Table 10. The intensification of warfare 16481815

Table 11. Militarization of the German principalities during the 1700s

Table 12. French and British naval casualties during the Revolutionary-Napoleonic Wars

Preface

In the course of the many years it has taken to prepare and write this book, I have incurred many debts. Not the least of them is to my editor at Penguin, Simon Winder, who has always been as supportive as he has been patient. I owe a very great deal to the generations of students at Cambridge I have been fortunate enough to teach and learn from. This particular acknowledgement goes well beyond conventional courtesy, for it is only when thinking about what I might say to them, and then improvising it in the lecture-or seminar-room, and seeking to deal with their criticisms, that any worthwhile ideas have come my way. Another activity conducive to creative thought is walking the dog, from home to the Faculty in the morning, out into the fields west of Cambridge at lunchtime and back home in the evening. For that reason, I have included Molly the Dalmatian among the dedicatees of this book. Although usually dozing, she has been present on her favourite armchair in the window-alcove of my office while every word of this book has been written. The Faculty of History has provided me with the ideal working environment, not least because it contains the largest dedicated history library in the country, and is only a couple of minutes away from one of the great libraries of the world, in the shape of the University Library. To the staffs of both libraries, especially Dr Linda Washington of the Seeley Historical Library, I express my warm appreciation. Of the very numerous colleagues, in and outside Cambridge, who have helped me in all sorts of ways, I single out for special thanks Chris Clark, Brendan Simms, Heinz Duchhardt, Charles Blanning, Ivan Valdez Bubnov, Eirwen Nicholson, Emma Griffin, David Brading, Robert Tombs, Robert Evans, Jo Whaley, Roderick Swanston, Martin Randall, Peter Dickson, Simon Dixon, Uwe Puschner, Ulrike Paul, Hagen Schulze, Munro Price, Bill Doyle, Julian Swann, Peter Wilson, Maiken Umbach and Jonathan Steinberg. I owe a special debt to Derek Beales and Hamish Scott, who heroically read my typescript and saved me from many sins of omission and commission. Not long after I began writing, my son Tom was born, to be joined three years later by Lucy. Although their arrival slowed progress appreciably, they also provided the necessary impetus to get me through the sticky periods. I could not have finished at all if my wife, Nicky, had not shouldered most of the burdens of parenthood, leaving me with just the pleasures. So it is right that her name should appear first on the list of dedicatees, just as she is first in my heart.

Tim Blanning

Cambridge, July 2006

Introduction

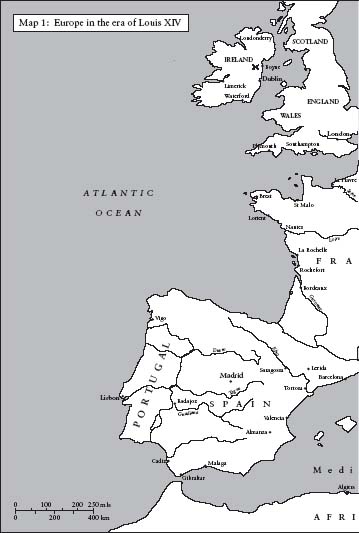

Every history of Europe has to start at some arbitrary date, unless of course an attempt is being made to cover everything since the emergence of Homo sapiens . But some dates are more arbitrary than others. Unfortunately, within the same period a date can mean something for one kind of human activity but very little for another. Seventeen eighty-nine, for example, has a thunderous resonance for politics but barely registers a bats squeak for music or the visual arts. Sixteen forty-eight is of that kind. It looks like a sensible starting point because it was in that year that the Peace of Westphalia was concluded, bringing to an end a war that had lasted thirty years and had inflicted more devastation on Europe than any previous conflict. Moreover, it settled at least two major issues, for the independence of the Dutch Republic from Spain was recognized, and the structure of German-speaking Europe was settled for a century, and a half. More important still was what lay behind those two settlements: the recognition that confessional pluralism had come to stay. Both Catholic and Protestant zealots would continue to dream dreams of the triumph of their true faiths, but the stalemate recognized in 1648 was never seriously threatened.

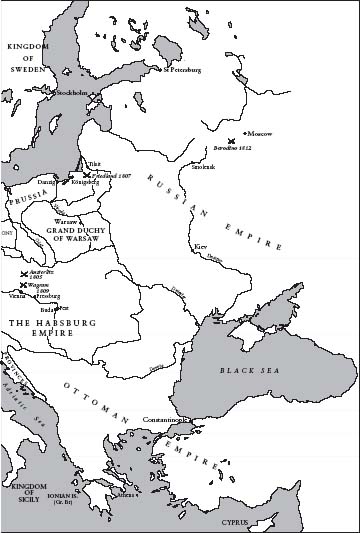

So this volumes initial date can be justified, but it must also be recognized that the Westphalian settlement left as much unfinished business as it concluded. The war between Spain and France sputtered on until the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659, and perhaps did not really end until the Bourbon inheritance of Spain was given international recognition in 1714. In the north and the east, the situation continued to be fluid, as Swedish supremacy was contested by first one power and then another in a confusing series of wars that did not end until the Peace of Nystad in 1721. What were to become the two dominant forces in international politics were the Second Hundred Years War between England and France, which did not begin until 1688, and the expansion of Russia, which did not begin until 1695. If anything, the direction being taken by domestic politics was even more uncertain. It was in 1648 that the French civil warsthe Frondes began and in 1649 that a republic was proclaimed in England, following the execution of Charles I. The very different resolutions of those conflicts had to await the beginning of Louis XIVs sole reign in 1661 and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 respectively.