Introduction

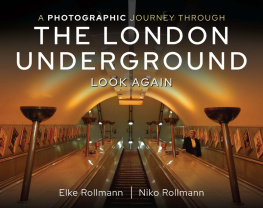

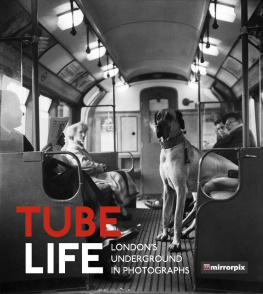

Fraud, liquidation, suicide and transportation for life: each of these occurred in the early history of Londons Underground Railway. If any author were to write a work of fiction which incorporated such bizarre chapters in its history it would be dismissed as beyond the world of fantasy. For the London Underground is not only the worlds oldest underground railway. It is also the one with the most extraordinary history. Its construction involved some of our most distinguished engineers though many of them are remembered for other reasons. John Fowler helped to design the Forth Bridge but he was a prominent contributor to the construction of the first underground railways. Isambard Kingdom Brunel built the Great Western Railway but he and his equally distinguished father, Marc Brunel, carried out pioneering work without which the deep level tubes could not have been built. Sir Joseph Bazalgette built Victorian Londons sewers but also made it possible for the District Line to run along the Embankment. Two prominent literary figures were also associated with the Underground Mark Twain and Sir John Betjeman. Sir Joseph Paxton, designer of the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851, put forward a proposal for a railway encased in glass to solve Londons transport problems which, though ingenious, was so expensive that it was rejected in favour of the Metropolitan Line which, on 9th January 1863, became the worlds first underground railway. The Times, which had condemned the Line as a utopian, hazardous proposition changed its tune and declared it the great engineering triumph of the day.

The London Underground has also made a major contribution to our artistic heritage. Celebrated twentieth century artists like Mabel Lucie Attwell, Rex Whistler and Graham Sutherland received their first commissions from the advertising department of the Underground. Bauhaus architecture was introduced to England through the design of stations on the Northern and Piccadilly Lines. The outstanding feature of Underground art, of course, is the tube map, now an instantly recognizable symbol of London throughout the world. Its designer, Harry Beck, who conceived it in a moment of idleness, received five guineas for his trouble!

Besides the distinguished artistic achievements there are also some bizarre entries in the record. Sir Edward Watkins Neasden Tower was designed to surpass the Eiffel Tower and to generate huge volumes of traffic for his Metropolitan Railway. Its sad remnant was blown up soon after his death to make way for Wembley stadium. Watkin also started to build the first Channel Tunnel so that his railway system, including the Metropolitan, could dispatch its passengers to Paris. Some oddities survive, including strange structures built alongside the Northern Line on the orders of Home Secretary Herbert Morrison to house the wartime government in an emergency. They are still there, odd relics of another age. The Underground even has its own unique species of mosquito!

And finally there are the crooks. Leopold Redpath was one of the last to be transported to Australia, for embezzling money intended to build the Metropolitan Line. Whitaker Wright perpetrated a number of swindles to raise money to build the Bakerloo Line and committed suicide in the Law Courts after being sentenced to seven years hard labour. Charles Tyson Yerkes, having earlier been gaoled in his native America for fraud, set about taking over the London Underground and left it on the verge of bankruptcy when he died in 1905. Without such people we wouldnt have the London Underground which, with all its faults, still makes life in London possible.

All these, and much else, are covered in the pages which follow.

The Pioneers

For more than two centuries before the development of the Underground, ideas had been put forward for dealing with Londons traffic problem. Most did not progress beyond the proposal stage. One, the forerunner of todays black cabs, was successful. The basic principles of another was incorporated into the Metropolitan Railway, the first Underground service to open, although the idea itself was never actually developed. This chapter covers some of the pioneering spirits behind these early ideas.

THE FAILURES

George Shillibeers Omnibus

On a visit to Paris in 1828 George Shillibeer, a coachbuilder, admired the Omnibus service which had been introduced there by Stanislas Baudry after trials in his native Nantes. Shillibeer launched a similar service in London on 4th July 1829, using his specially designed vehicle, along the New Road, between Paddington Green and the Angel. He offered five services daily in each direction, charging the considerable sum of one shilling and sixpence for passengers inside the coach and one shilling for those outside. His newspaper advertisements emphasized that, a person of great respectability attends his Vehicle as Conductor; and every possible attention will be paid to the accommodation of ladies and children. Such reassurances were necessary for this novel form of transport as gentry were not accustomed to sharing conveyances with strangers. Sadly, the fares were too high for most and, having deposited his passengers at the Angel, Shillibeer was still leaving them to find their way into the City. Within a year Stanislas Baudry, faced with financial ruin, drowned himself in the Seine while George Shillibeer, more prudently, fled to France to escape his creditors. He later returned to England and, after a short spell in a debtors prison, emerged to redesign his omnibus as a funeral carriage (which it always resembled) and thereby recover his fortunes.

Moseleys Crystal Way

In 1855 William Moseley, an architect, put forward a scheme to the Parliamentary Select Committee on Metropolitan Communications. He proposed to build a railway below street level between St Pauls Cathedral and Oxford Circus, with a branch to Piccadilly Circus. It would be covered by a wrought-iron grid, free of traffic, along which pedestrians could walk for one penny and watch the trains beneath them. Tolls for bridges across the Thames were at this time commonplace so the idea of charging a penny to use such a footway was not outrageous. The footway itself would be enclosed within a glass canopy (hence the Crystal title) with shops, flats and hotels on either side. It would have been the original Victorian shopping mall. The trains would be pneumatic railways, driven by atmospheric pressure, thus generating neither steam nor smoke. The cost was estimated at 2 million. The Committee felt that this scheme, though ingenious, was not value for money and it had the additional and fatal flaw of not connecting with any of the main-line stations.

Paxtons Great Victorian Way

A more ambitious scheme came from Sir Joseph Paxton, the creator of the Crystal Palace. In 1855 he proposed a railway 12 miles long, linking all of Londons mainline termini and crossing the Thames three times. It would be built above ground and, like Moseleys, be encased by a glass arcade with shops and houses on either side. The arcade would protect residents and shoppers from the smells of smoking chimneys and the stench of sewage flowing into the reeking Thames. It would for that reason alone have been a desirable area for pedestrians and, by linking all the main termini, would have removed a great deal of traffic from the streets. Paxton argued that for the fortunate residents the atmosphere would be almost equal to going to a foreign climate [and] would prevent many infirm persons being obliged to go into foreign countries in the winter! Once again a pneumatic railway was proposed and Paxton suggested that the staggering cost of 34 million for the patriotically named Great Victorian Way should be underwritten by the Treasury. The MPs, while noting its many features of remarkable novelty, felt that the scheme was rather too costly.