CHAPTER I.

Table of Contents

A REVOLUTION must occur in the condition and sentiments ofmankind more decided than we have any reason to expect that thelapse of ages will produce, before the mighty events whichdistinguished the spring of 1814 shall be spoken of in otherterms than those of unqualified admiration. It was then thatEurope, which during so many years had groaned beneath themiseries of war, found herself at once, and to her remotestrecesses, blessed with the prospect of a sure and permanentpeace. Princes, who had dwelt in exile till the very hope ofrestoration to power began to depart from them, beheld themselvesunexpectedly replaced on the thrones of their ancestors;dynasties, which the will of one man had erected, disappearedwith the same abruptness with which they had arisen; and theinfluence of changes which a quarter of a century of rapine andconquest had produced in the arrangements of general society,ceased, as if by magic, to be felt, or at least to be acknowledged.It seemed, indeed, as if all which had been passing during thelast twenty or thirty years, had passed not in reality,but in a dream; so perfectly unlooked for were the issues ofa struggle, to which, whatever light we may regard it,the history of the whole world presents no parallel.

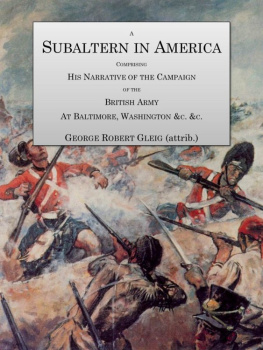

At the period above alluded to, it was the writer's fortune toform one of a body of persons in whom the unexpected cessation ofhostilities may be supposed to have excited sensations morepowerful and more mixed than those to which the commonoccurrences of life are accustomed to give birth. He was thenattached to that portion of the Peninsular army to which thesiege of Bayonne had been intrusted; and on the 28th of Aprilbeheld, in common with his comrades, the tri-coloured flag,which, for upwards of two months, had waved defiance from thebattlements, give place to the ancient drapeau blanc of theBourbons. That such a spectacle could be regarded by anyBritish soldier without stirring up in him strong feelings ofnational pride and exultation, is not to be imagined. I believe,indeed, that there was not a man in our ranks, however humble hisstation, to whose bosom these feelings were a stranger. But theexcitation of the moment having passed away, other and no lesspowerful feelings succeeded; and they were painful, or thereverse, according as they ran in one or other of the channelsinto which the situations and prospects of individuals notunnaturally guided them. By such as had been long absent fromtheir homes, the idea of enjoying once more the society offriends and relatives, was hailed with a degree of delight tooengrossing to afford room for the occurrence of any otheranticipations; to those who had either no homes to look to, orhad quitted them only a short time ago, the thoughts ofrevisiting England came mixed with other thoughts, littlegratifying, because at variance with all their dreams ofadvancement and renown. For my own part I candidly confess, thatthough I had just cause to look forward to a return to the bosomof my family with as much satisfaction as most men, therestoration of peace excited in me sensations of a very equivocalnature. At the age of eighteen, and still enthusiasticallyattached to my profession, neither the prospect of a reduction tohalf-pay, nor the expectation of a long continuance in asubaltern situation, were to me productive of any pleasurableemotions; and hence, though I entered heartily into all thearrangements by which those about me strove to evince theirgratification at the glorious termination of the war, it must beacknowledged that I did so, without experiencing much of thesatisfaction with the semblance of which my outward behaviourmight be marked.

EXPECTED EMBARKATION FOR AMERICA.

Such being my own feelings, and the feelings of the greatmajority of those immediately around me, it was but natural thatwe should turn our views to the only remaining quarter of theglobe in which the flame of war still continued to burn. Thoughat peace with France, England, we remembered; was not yet atpeace with the United States; and reasoning, not as statesmen butas soldiers, we concluded that she was not now likely to makepeace with that nation till she should be able to do so upon herown terms. Having such an army on foot, what line of policycould appear so natural or so judicious as that she shouldemploy, if not the whole, at all events a large proportion of it,in chastising an enemy, than whom none had ever proved morevindictive or more ungenerous? Our view of the matter accordinglywas, that some fifteen or twenty thousand men would be forthwithembarked on board of ship and transported to the other side ofthe Atlantic; that the war would there be carried on with avigour conformable to the dignity and resources of the countrywhich waged it; and that no mention of peace would be made tillour general should be in a situation to dictate its conditions inthe enemy's capital.

Whether any design of the kind was ever seriously entertained, orwhether men merely asserted as a truth what they earnestlydesired to be such, I know not; but the white flag had hardlybeen hoisted on the citadel of Bayonne, when a rumour becameprevalent that an extensive encampment of troops, destined forthe American war, was actually forming in the vicinity ofBordeaux. A variety of causes led me to anticipate that thecorps to which I was attached would certainly be employed uponthat service. In the progress of the war which had been justbrought to a conclusion, we had not suffered so severely as manyother corps; and though not excelling in numbers, it is butjustice to affirm that a more effective or better organizedbattalion could not be found in the whole army. We were all,moreover, from our commanding officer down to the youngestensign, anxious to gather a few more laurels, even in America;and we had good reason to believe that those in power were notindisposed to gratify our inclinations. Under thesecircumstances we clung with fondness to the hope that our martialcareer had not yet come to a close; and employed the space whichintervened between the eventful 28th of April and the 8th of thefollowing month, chiefly in forming guesses as to the point ofattack towards which it was likely that we should be turned.

ENCAMPMENT NEAR PASSAGES.

Though there was peace between the French and British nations,the form of hostilities was so far kept up between the garrisonof Bayonne and the army encamped around it, that it was only byan especial treaty that the former were allowed to send outparties for the purpose of collecting forage and provisions fromthe adjacent country. The foraging parties, however, beingpermitted to proceed in any direction most convenient tothemselves, the supplies of corn and grass, which had heretoforeproved barely sufficient for our own horses and cattle, soonbegan to fail, and it was found necessary to move more than onebrigade to a distance from the city. Among others, the brigade ofwhich my regiment formed a part, received orders on the 7th ofMay to fall back on the road towards Passages. These orders weobeyed on the following morning; and after an agreeable march offifteen or sixteen miles, pitched our tents in a thick wood,about half-way between the village of Bedart and the town ofSt. Jean de Luz. In this position we remained for nearly a week,our expectations of employment on the other side of the Atlanticbecoming daily less and less sanguine, till at length all doubtson the subject were put an end to by the sudden arrival of adispatch, which commanded us to set out with as little delay aspossible towards Bordeaux.