PREFACE

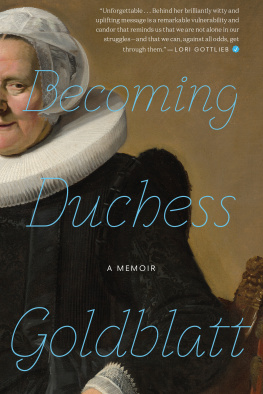

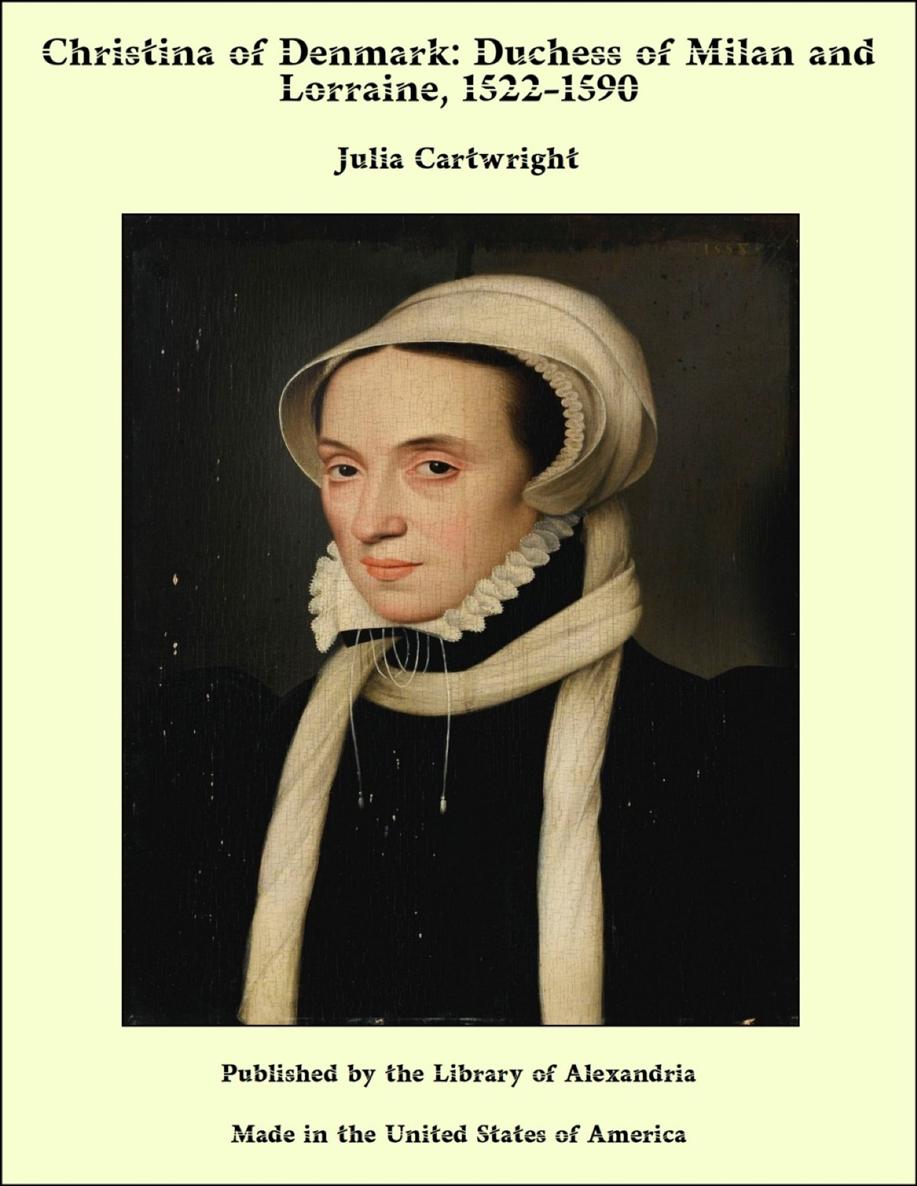

Christina of Denmark is known to the world by Holbein's famous portrait in the National Gallery. The great Court painter, who was sent to Brussels by Henry VIII. to take the likeness of the Emperor's niece, did his work well. With unerring skill he has rendered the "singular good countenance," the clear brown eyes with their frank, honest gaze, the smile hovering about "the faire red lips," the slender fingers of the nervously clasped hands, which Brantme and his royal mistress, Catherine de' Medici, thought "the most beautiful hands in the world." And in a wonderful way he has caught the subtle charm of the young Duchess's personality, and made it live on his canvas. What wonder that Henry fell in love with the picture, and vowed that he would have the Duchess, if she came to him without a farthing! But for all these brave words the masterful King's wooing failed. The ghost of his wronged wife, Katherine of Aragon, the smoke of plundered abbeys, and the blood of martyred friars, came between him and his destined bride, and Christina was never numbered in the roll of Henry VIII.'s wives. This splendid, if perilous, adventure was denied her. But many strange experiences marked the course of her chequered life, and neither beauty nor virtue could save her from the shafts of envious Fortune. Her troubles began from the cradle. When she was little more than a year old, her father, King Christian II., was deposed by his subjects, and her mother, the gentle Isabella of Austria, died in exile of a broken heart. She lost her first husband, Francesco Sforza, at the end of eighteen months. Her second husband, Francis Duke of Lorraine, died in 1545, leaving her once more a widow at the age of twenty-three. Her only son was torn from her arms while still a boy by a foreign invader, Henry II., and she herself was driven into exile. Seven years later she was deprived of the regency of the Netherlands, just when the coveted prize seemed within her grasp, and the last days of her existence were embittered by the greed and injustice of her cousin, Philip II.

Yet, in spite of hard blows and cruel losses, Christina's life was not all unhappy. The blue birdthe symbol of perpetual happiness in the faery lore of her own Lorrainemay have eluded her grasp, but she filled a great position nobly, and tasted some of the deepest and truest of human joys. Men and women of all descriptions adored her, and she had a genius for friendship which survived the charms of youth and endured to her dying day. A woman of strong affections and resolute will, she inherited a considerable share of the aptitude for government that distinguished the women of the Habsburg race. Her relationship with Charles V. and residence at the Court of Brussels brought her into close connection with political events during the long struggle with France, and it was in a great measure due to her exertions that the peace which ended this Sixty Years' War was finally concluded at Cteau-Cambrsis in 1559.

Holbein's Duchess, it is evident, was a striking figure, and her life deserves more attention than it has hitherto received. Brantme honoured her with a place in his gallery of fair ladies, and the sketch which he has drawn, although inaccurate in many details, remains true in its main outlines. But with this exception Christina's history has never yet been written. The chief sources from which her biography is drawn are the State Archives of Milan and Brussels, supplemented by documents in the Record Office, the Bibliothque Nationale, the Biblioteca Zelada near Pavia, and the extremely interesting collection of Guise letters in the Balcarres Manuscripts, which has been preserved in the Advocates' Library at Edinburgh. A considerable amount of information, as will be seen from the Bibliography at the end of this volume, has been collected from contemporary memoirs, from the histories of Bucholtz and Henne, and the voluminous correspondence of Cardinal Granvelle and Philip II., as well as from Tudor, Spanish, and Venetian State Papers.

In conclusion, I have to acknowledge the kind help which I have received in my researches from Monsignor Rodolfo Maiocchi, Rector of the Borromeo College at Pavia, from Signor O. F. Tencajoli, and from the keepers of English and foreign archives, among whom I must especially name Signor Achille Giussani, of the Archivio di Stato at Milan, Monsieur Gaillard, Director of the Brussels Archives, and Mr. Hubert Hall. My sincere thanks are due to Count Antonio Cavagna Sangiuliani for giving me permission to make use of manuscripts in his library at Zelada; to Monsieur Leon Cardon for leave to reproduce four of the Habsburg portraits in his fine collection at Brussels; and to Mr. Henry Oppenheimer for allowing me to publish his beautiful and unique medal of the Duchess of Milan. I must also thank Sir Kenneth Mackenzie and the Trustees of the Advocates' Library for permission to print a selection from the Balcarres Manuscripts, and Mr. Campbell Dodgson and Mr. G. F. Hill for the kindness with which they have placed the treasures of the British Museum at my disposal. Lastly, a debt of gratitude, which I can never sufficiently express, is due to Dr. Hagberg-Wright and the staff of the London Library for the invaluable help which they have given me in this, as in all my other works.

JULIA CARTWRIGHT.

Ockham ,

Midsummer Day, 1913.