This edition first published in 2008 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 1984 by Victor Gollancz Ltd

Copyright the Estate of David Kerr Cameron 1984

Introduction copyright Jack Webster 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN13: 978 1 84158 710 3

ISBN10: 1 84158 710 9

eISBN: 978 0 85790 909 1

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Hewer Text (UK) Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman Ltd, Reading

Acknowledgements

This is a book of many voices. So intertwined is the culture of the North-East Lowlands with its countryside that it would have been inconceivable to omit the work of its poets and writers. Wittingly and unwittingly, they were the observers of the scenes, moods and seasons of the older landscape, earlier recorders of that ceaseless conflict of men with the soil. I have acknowledged the sources of their words wherever I have used them; I am deeply indebted to all of them. In particular, for generously allowing the use of copyright material, I should like to thank Flora Garry (for permitting me to quote from her work); the Aberdeen University Press and the Charles Murray Memorial Trust (for allowing the inclusion of work by John C. Milne and Charles Murray respectively); the Bailies of Bennachie; John Stewart Collis; Mr Gavin Muir and Chatto and Windus; and publishers Paul Harris, Faber and Faber, Oxford University Press, Thomas Nelson, Century and Robert Hale. Excerpts from the work of Lewis Grassic Gibbon are reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown Ltd, London, on behalf of the estate of James Leslie Mitchell Ray Mitchell 1967.

Henry Stephens The Book of the Farm, first published in 1844, ran to later editions. The two outstanding sources of the old bothy balladry are John Ords Bothy Songs and Ballads and Gavin Greigs Folk-Song of the North-East.

The photographs have been gathered from several sources, individually acknowledged. My thanks are due to all those who helped me to locate them, and in particular to John A. Fraser, secretary of The Clydesdale Horse Society, and Douglas M. Spence of D.C. Thomson.

D.K.C.

Introduction

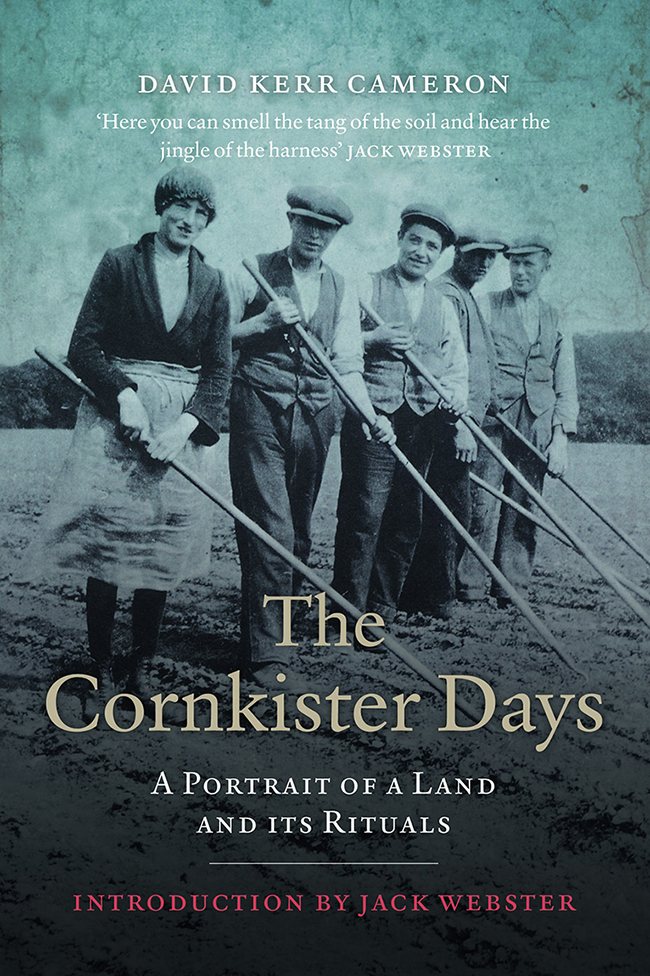

The cornkister is the ballad of farming life, much in evidence in the North-East Lowlands of Scotland during those years when the countryside was populated with a vibrant, hard working, good-humoured people. Although these folk have long since vanished, by good fortune the broader canvas of their bygone age is captured in The Cornkister Days, a literary masterpiece by a man who caught the tail-end of an era and was blessed with the talent to observe and express it as few others could have done. The book completes a trilogy that begins with The Ballad and the Plough and is preceded by Willie Gavin, Crofter Man. Like its companions it both entertains and informs the reader about rural life in Scotland from the mid 1800s to modern times.

For a variety of reasons, David Kerr Cameron has yet to gain his rightful literary recognition in Scotland, but this new edition will hopefully go some way to put this right. The author was an Aberdonian who did not publish his first work until he was fifty and, sadly, left us in 2003, at the age of seventy-four. His own story makes interesting reading. Cameron was brought up in a cottar house at Tarves in Aberdeenshire, where his father was a typical horseman of his day. His paternal grandfather was grieve to Lord Aberdeen at the nearby Haddo House estate while his maternal grandfather was a neighbouring crofter, Willie Porter, on whom his character Willie Gavin is based.

Camerons own childhood of the 1930s saw the last years of the old farming traditions in which his own roots were firmly planted. He was called up for National Service in the RAF after the war, then went into agricultural engineering, for which he had a natural bent.

But he never forgot the school essays which had prompted his headmaster to suggest that he should consider a career in journalism, and eventually he went that way, first working on the Kirriemuir Herald and then the Aberdeen Press and Journal. Even when he joined the Daily Telegraph in London, however, it was as a sub-editor, not a writer. The novelist Graham Greene was among those who maintained that all writers should first become sub-editors, a discipline that teaches about cutting the waffle and getting to the point. So over time he quietly honed his craft.

Perhaps it was his London experience that prompted Cameron to re-examine his own roots and apply himself to the task of writing about them. Travelling into the metropolis on the Underground, frozen looks greeted his attempts at conversation, and at his office desk he may well have reminisced about a better way of life, the way of the old Scots folk he remembered from the days of his own youth

Cameron was one of a band of Scottish writers who looked back on their heritage from a distance. Lewis Grassic Gibbon, for example, lived in Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire and Jessie Kesson made her home in Muswell Hill. Further afield, the Doric poet Charles Murray settled in South Africa, and of course the great Robert Louis Stevenson was based in Samoa. Despite the hardships of living away from Scotland, this experience of exile gave them a freedom to look at their own lives and roots in a wider perspective.

After The Ballad and the Plough and Willie Gavin, Cameron realised there was yet another book to be written if he was to complete the picture of the old North-East farming landscape. It would tell of life in the fields, the work routines, the hardships, the simple joys, the humour and quiet dignity of a race that was the salt of the earth. He would sprinkle it liberally with the work of other North-East writers and poets like J.C. Milne and Flora Garry, a lady who joins that band of Aberdonians, like David Toulmin and Cameron himself, who displayed their talents late in life.

All was set down in perfectly crafted prose that characterizes all his writing. His poignant description of the rhythm of the seasons, whilst showing the influence of that North-Easts greatest writer, Lewis Grassic Gibbon, is unmistakably his own: It was a land above all where life moved against the tapestry of the year, the immutability of the seasons, absorbing their rhythms and immemorial rituals: ploughing, harrowing, sowing, reaping, threshing and the tending of livestock. It had a soul and a pulse-beat, a dreichness that was not unlovely. Sometimes it stole the heart.