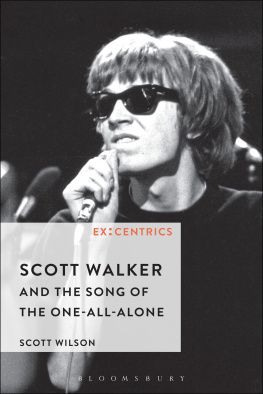

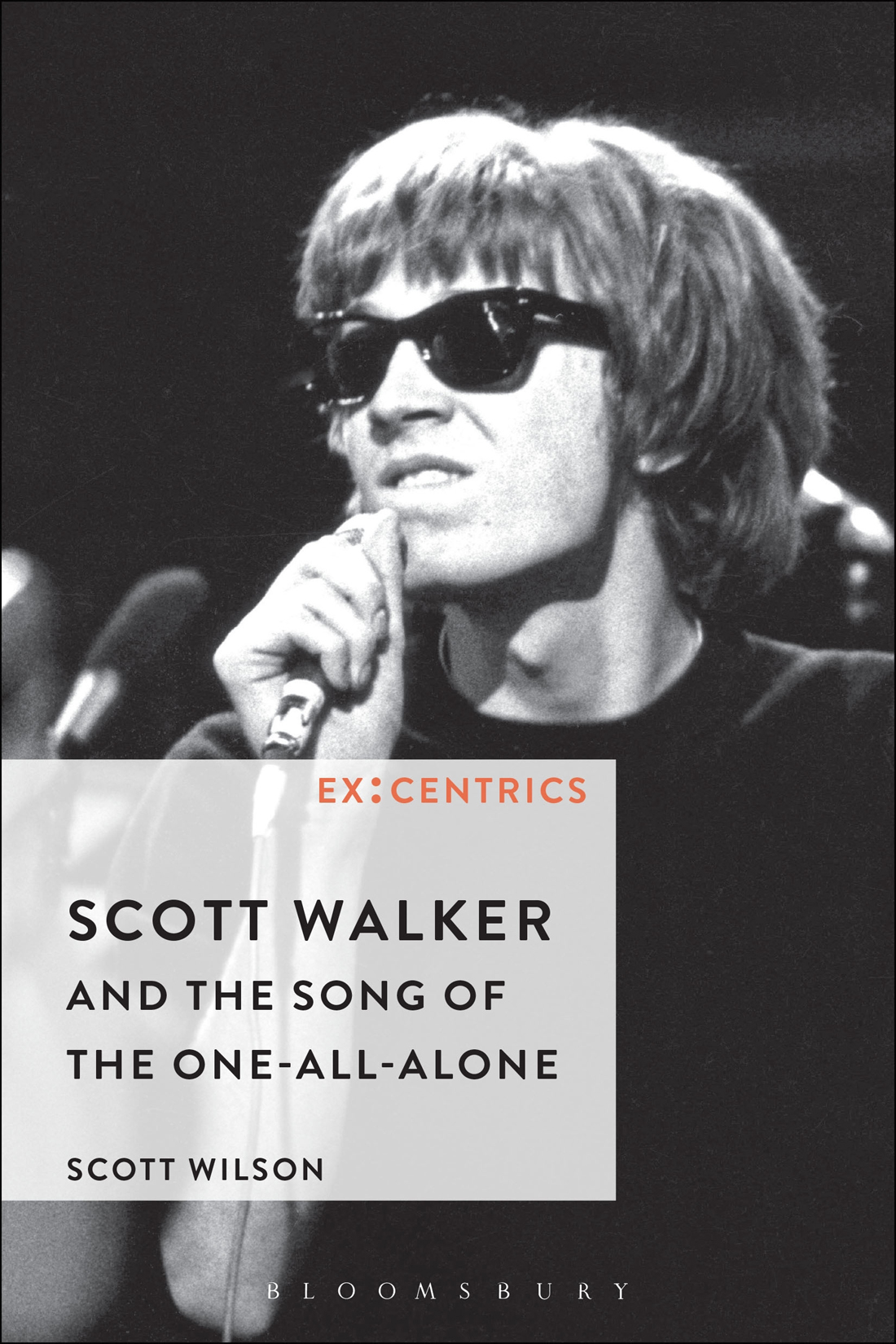

Scott Walker and the Song of the One-All-Alone

ex:centrics

Series Editors

Greg Hainge and Paul Hegarty

Books in the Series

Philippe Grandrieux: Sonic Cinema by Greg Hainge

Gallery Sound by Caleb Kelly

For Jacqueline

Scott Walker and the Song of the One-All-Alone

Scott Wilson

Contents

The existentialist pop star

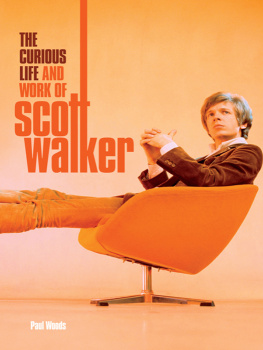

Scott Walker, experimental pop hero, dies, announced the headline in The Guardian on March 26 2019. Though not front page, the piece heralded a number of tribute-pieces from Alex Petrides, Rob Young and Eimear MacBride, alongside soundbites from a range of mainstream and avant-garde figures such as Thom Yorke, Damon Albarn, Cosey Fanni Tutti and Agnes Obel. Super fan Marc Almonds Instagram account was quoted, hailing Walker as an absolute musical genius, existential and intellectual and a star right from the days of the Walker Brothers (). While at first sight Scott Walker might seem a perfect artist to fit the brief of the Ex:Centrics series that sets out to examine non-mainstream artists, he has not been overlooked. Walker remains a significant if perplexing figure in the UK and elsewhere in Europe. Indeed, his death was reported by all the mainstream newspapers in the UK. Every rare new album over the last 20 years of his life was widely reviewed and generated online comment.

But as The Guardian headline suggests, with its contradictory conjunction of pop and the experimental, Walkers career is difficult if not impossible for many commentators to fathom. Andy Williams re-inventing himself as Stockhausen ().

While any hint of pretention in a pop or rock star immediately brings out the violence in a critic, the problem is also that people are still discovering and falling in love with Walkers sublime quasi-orchestral pop, particularly the four solo albums of the late 1960s. These were celebrated on 2017 at the Royal Albert Hall when Prom 15 was dedicated to The Songs of Scott Walker (1967-70) (25.07.17). While the Heritage Orchestra did justice to Walkers imagination, Wally Stotts arrangements and John Frantzs production of the originals, the vocal efforts of Jarvis Cocker, John Grant, Suzanne Sandfr and Richard Hawley more than demonstrated the unsurpassed quality and skill of Walkers singing. With this embrace from the heart of the musical establishment, fifty years after the fact, and now following his death, Scott Walker seems set to become a kind of national treasure or at least in the shape of a particular romantic image, a cameo from the 1960s set in amber. It seems a strange circuitous route that closes off the journey that Walker actually takes throughout the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, producing songs that I would wager may take at least another fifty years to return in tribute to the Royal Albert Hall.

The 22-year-old Scott Walker arrived in the UK as the bass player of the Walker Brothers in February 1965; the bands calling-card a new single called Love Her produced by Jack Nitzsche. Nitzsche was at the time Phil Spectors arranger and co-creator of the famous wall of sound associated : 12).

After college in LA, Walker gigged with various bands playing bass until hooking up with John Maus. Renaming themselves Walker Brothers, John and Scott played the Sunset Strip, bringing beat music to the supper clubs: young lounge lizards among the go-go girls and film stars, visually if not musically at this time aping the swinging sophistication of Jack Jones and Frank Sinatra. They would achieve a six months residency at the famous Whisky A Go Go club, preceding the Doors occupancy as house band by two years. Both LA groups eschewed the burgeoning LA jingle-jangle folk-rock associated with the Byrds, and the Walker Brothers development paralleled the Doors use of jazz-inflected motifs. When Scott took on lead vocal duties, both bands were fronted by the two greatest baritone voices in pop and rock. It was at the Whisky that Gary Leeds, who had been drumming for P.J. Proby, joined the band and suggested they seek their fortune in London.

In the UK the Walker Brothers produced three hit albums, Take It Easy With The Walker Brothers (1965), Portrait (1966) and Images (1967), alongside a series of unforgettable pop songs such as Take It Easy on Yourself, My Ship Is Coming In and The Sun Aint Gonna Shine Anymore that rank among the best recordings of the 1960s. : 25). For Walker, however, existentialism was not simply a stylistic, lifestyle aspiration and a set of fashion clichs (Roberts: 24); it remained throughout his life a touchstone of his commitment to his art. This first flourished in the series of eponymous, numbered solo albums that Walker produced from 1967 to 1970. European bohemianism and the dramatic appeal of youthful angst provides the mise-en-scene for the startling ambition of these existentialist pop records. The inspired use of orchestral arrangements and lyrical themes drawn from the European avant-garde, Chanson franaise , the cinema of Ingmar Bergman, French New Wave cinema and British social realism make these albums unique. Significantly, Walkers distinctive cover versions of Jacques Brels songs were partly responsible for introducing the Belgian chanteur to the English-speaking world.

According to Sarah Bakewells best-selling re-evaluation of the philosophical movement, At the Existentialist Caf (Romanticism, existentialism poses the question of existence and how one might take up the responsibility and burden of freedom: in particular the freedom to become who you are in the paradoxical formulation of Nietzsche. Accordingly, the vicissitudes of everyday life and the death that defines it for the one living took on for these writers more significance than abstract concepts and mathematical formulae. The philosophy thus leant itself to forms of expression found in novels, plays, film and music rather than to academic theses. The struggle to take up the challenge of becoming oneself in contradistinction to an identity that is socially expected and conventional or even successful provides the animating focus of much of the literature. The importance of the for-itself, however, is for Sartre not at all the basis for hedonistic pleasures or solipsistic self-regard. It is the basis for an engagement , a commitment that calls upon ones very life. To give up on the desire to commit oneself in this way constitutes for Sartre mauvaise foi or bad faith. In the 1950s Sartre sought to evade the tentacles of bad faith by becoming fully committed to Marxism. While Scott Walker retained a strong interest in politics, the goal to become for-himself meant a Camusian revolt against the pop spotlight and a renewed commitment to his art that eventually produced work of an extraordinary, uncompromising quality.

But not before his own collapse into what he has described as his years of bad faith (order to discover his own cavernous and disturbing sound world. The mining of this world would take a long time: new albums came along on average only every ten years. But when they did they were like nothing else in the world of rock and pop, even as they drew from that world in combination with other elements from classical music to modern jazz, musique concrte and industrial noise.

As I have suggested, there is an ethic in existentialism that one should not take the conventional or popular path, an ethic that was transformed into a style that informed pop and rock rebellion, the desire for authenticity and the demand to keep it real. It is a style that has been indelibly associated with both artistic and commercial success, the imbalance between the two often marking degrees of sell out. I am going to argue that this familiar logic does not apply to Scott Walker. Certainly, Walker has not followed either the mainstream or alternative path, with the result that he has frequently produced work that is a commercial failure. Neither pop nor punk, Walker has implacably followed his own path, gone his own way there being, as Nietzsche insists, no correct or right way. As such, it is difficult, if not impossible, to judge whether such uncompromising work is an artistic success; there are no significant comparators. In that regard the existentialism of the works for-itself is profound. The unfamiliarity of the work means that unpopularity is guaranteed, the rule rather than the exception. Consequently, his fans and listeners are required to show the same commitment to his art as he does; many do not. Yet, in following the ethical path of the unpopular, Walker has arrived at a unique sound according to his own method that has produced a genuinely new form of song. In the phrase of Devin William Daniels, an online enthusiast, he may be not only one of the truly strangest musicians of our time, but one of the truly incommensurable (). If you are strange and incommensurable then you are neither mainstream nor extreme, nor are you anywhere in between. You are one all alone.