Copyright 2005 by Lynn Freed

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

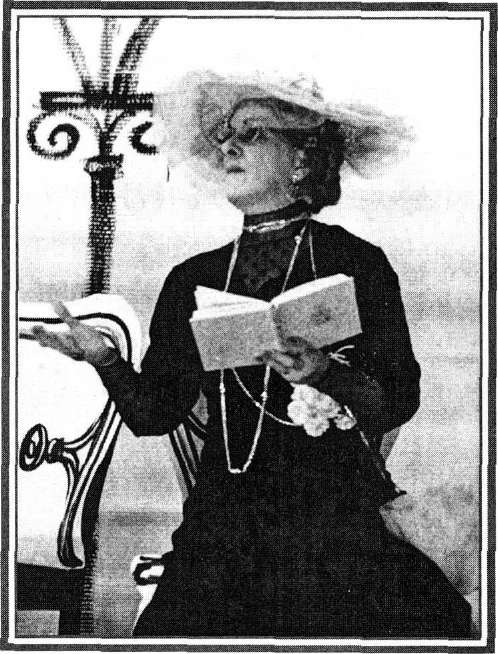

The photos accompanying the stories Doing Time and Home on the Range are by Mary Pitts and are reproduced with her kind permission. The photo for Taming the Gorgon is by Vicky Cass and is reproduced with her kind permission.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Freed, Lynn.

Reading, writing, and leaving home: a life on the page/

Lynn Freed.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Freed, Lynn. 2. Authors, South African20th centuryBiography. 3. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. 4. English teachersUnited StatesBiography. 5. South African AmericansBiography. 6. FictionAuthorship. I. Title.

PR9369.3.F68Z47 2005

823'.914dc22 2005002397

ISBN -13: 978-0-15-101132-2 ISBN -10: 0-15-101132-X ISBN -13: 978-0-15-603034-2 (pbk) ISBN -10: 0-15-603034-9 (pbk)

e ISBN 978-0-547-94064-9

v2.0816

for Rosemary

A Childs Reading

O NLY LONG AFTER I WAS OLD ENOUGH to read for myself, did I really make the connection between literature and the printed word. My mother, whose first and abiding love was for the theatre, preferred to tell her own versions of the stories other parents read to their children from books. This way she could add characters at will, eliminate others, change the plot around, and thus string out the story into a series of episodic cliff-hangers that would last over a period of weeks or even months. The books themselves remained on our shelves, mouldy and full of bookworm in the hot, damp region of South Africa in which we lived.

The first story I remember her delivering was Charles Kingsleys Water-Babies, one of those strange English tales for children, in which bad people with money and foul tempers bully small, poor, helpless, good people, often children. Good does triumph in the end, of course, but not before lessons have been learned and the wicked punished. In this particular story, Tom is a very young chimney sweep, who is employed by the evil Mr. Grimes. Tom runs away, falls into a river, and meets there the water-babies of the title, with whom he takes up residence.

My mother, falling into an old literary trap, managed to make the evil characters, both above and below the water, far more appealing than Tom. As she came forth with yet another demon lying in wait for him, and hetoo good to be true and a bit stupidaccomplished another narrow escape, I lay shivering with delight. When I finally came to read the book itself, with its angelic illustrations of the water-babies and even the rather predictably grumpy Mr. Grimes, I felt terribly let down. Not only was my mothers version better, but it seemed truer as well.

What I did take on faith in this story, howeverand in so many other stories fed to South African children when I was growing upwas that, contrary to what was true in my world, small white boys could be made to work for a living (girls, tooto wit the many tales of English waifs dressed in rags, who skivvied all day and were then consigned to freezing London attics to pray and shiver through the night). Also that snow fell at Christmastime, that there were fires rather than flower arrangements in fireplaces, and that hedgehogs, toads, foxes, and molesnot monkeys, snakes, and iguanas, the urban animals of my childhoodwere the sorts of creatures which, in fiction, would stand up on their hind legs, don clothing, and sally forth into a story.

More than this, I believed that these strange customs and creatures were more real than those of the world I lived in, and far more worthy of fiction. The real world of my childhooda large subtropical port on the Indian Ocean, with beaches and bush and sugarcane and steaming heat, a strict Anglican girls school, massive family gatherings on Friday nights and Jewish holidays, and then my parents theatre world, the plays my mother directed, my father learning his lines every evening in the bath, both of them off to rehearsal night after night, leaving the next episode of her story for me to listen to on a huge reel-to-reel tape recorderthis world did not exist, not even peripherally, in the literature available to me. Nor did I think that it should.

What I did encounter of indigenous South African literature came later, much later, at school. There, the odd poem or book (Roy Campbell, Laurens van der Post) would be included in an otherwise watertight English syllabus: Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Thackeray, Dickens, Hardy, and, of course, the King James Bible. There wasnt even any venturing into Bloomsbury or, across the Atlantic, to America, absolutely not. Our history teacher, who, like most of the teachers in the school was English, stopped short of teaching the First World War, which, said she in 1960, was still controversial.

The Africa of popular imagination came to us via the radio. Until the midseventies, there was no television in South Africa, and so it was radio that offered programs like Tarzan of the Apes, to which I listened every evening in the kitchen with the servants. There we stood in rapt silence next to the fridge, on top of which the wireless sat in a place of honour.

Meanwhile, the fact that I was learning to read did not bring my mothers nightly episodes to an end, far from it. She moved on to the Brothers Grimm, to Rudyard Kiplings Just So Stories (a world much more familiar to me than Tarzans jungle), to The Wind in the Willows, which never engaged me, not even her version of it, and then to the plays of J. M. Barrie Quality Street; Peter Pan; and my favourite, The Admirable Crichton. These she told from the point of view of whichever character she herself happened to have played on the stage.

The books I was beginning to read for myselfby English childrens author, Enid Blytonwere considered lower than comics by the local cognoscenti, chief among whom was one of my fathers sisters, a psychologist. My mother, a natural foe to my fathers family, to the whole idea of psychology, and, indeed, to censorship itself (except for Disney, which she would not countenance), lifted her ample nose in scorn. Blytons books might trespass upon the rudimentary borders of correctitude being laid down, even then, by the likes of my aunt, but they had me reading for once, lying quietly on the verandah swing seat or down in the summerhouse, and then rushing back into the house to ask my mother to take a few more out of the library for me the next day.

What Blyton understood very well, even in her Noddy books for the very young, was the universal desire of children to escape from the sovereignty of adults. And so, the fact that Noddy had his own car, which, like him, was an animated toy, and that he made off in it with Big Ears, his friend, or that later, in Blytons preadolescent novels, Five Go Off in a Caravan, Hollow Tree House, The Naughtiest Girl in the School, there were rebels and runaways and naughty children finding adventure beyond the palethis freedom was a wonderful thing for a girl living at the bottom of Africa and dreaming of leaving herself one day, somehow, for the real world.

Unlike my mother, I was not a natural reader. I read slowly and quite haphazardly. As the youngest child in a large household of family and servants, I spent most of my time unsupervised, much of it outdoors. It was here that I was most alive to adventure and fantasy, creating grandiose scenarios from the top of the mango tree or taking off on my bicycle to explore. With books it was different. I read when it was dark, when it rained, when I was sick, or when I felt like company.

Next page