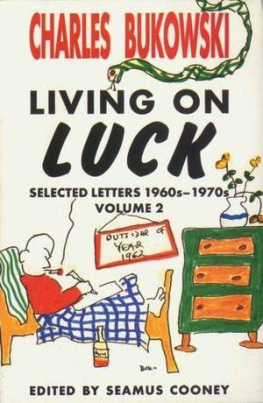

Charles Bukowski - Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s

Here you can read online Charles Bukowski - Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2007, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2007

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

SELECTED LETTERS 1960s1970s VOLUME 2

This second volume of Bukowskis letters begins, like volume 1, in the 1960s, thanks to the recovery of additional interesting letters from that decade. As that decade ends, Bukowski is liberated from the drudgery of his post office job and embarks with some trepidation on his career as a professional writer, encouraged by a small regular stipend from his publisher John Martin, who undertook to pay him $100 a month to enable him to write fulltime. Throughout the 1970s, as royalties begin to overtake the stipend and he gradually gains confidence that he will be able not merely to survive but to prosper in this new career, the letters return again and again with wonder to his sense of how lucky he is to enjoy being able to live by writing. By the end of the decade, hes the owner of a comfortable house and a new BMW . His worries now are how to protect his fruit trees from frost, how to lower his tax liability, and how to deal with Hollywood directors and stars.

As in volume 1, the letters have been selected and transcribed from photocopies furnished by libraries and individuals. Bukowskis correspondence was astonishingly voluminous, and only selections are given from most letters. Editorial omissions are indicated by asterisks in square brackets, thus: [***]. Ellipses in the original letters are indicated by three dots. Bukowski often typed in CAPITALS for emphasis or for titles. Here, book titles are printed in italics , poem titles in quotes, and emphatic capitals in SMALL CAPS .

Dates are regularized and sometimes supplied from postmarks or guessed at from other evidence. A few spelling errors have been silently corrected. Salutations and signatures are for the most part omitted, except for a few examples that give the characteristic flavor. Some attempt is made to preserve Bukowskis layout, which at times includes multiple margins, but a printed book cannot reproduce such effects unaltered. As in the previous volume, a few letters have been printed verbatim to give the flavor of a completely unedited letter.

References to Hank in the editorial matter are to Neeli Cherkovskys biography of Bukowski, published by Random House in 1991.

[To John William Corrington]

January 17, 1961

Hello Mr. Corrington:

Well, it helps sometimes to receive a letter such as yours. This makes two. A young man out of San Francisco wrote me that someday they would write books about me, if that would be any help. Well, Im not looking for help, or praise either, and Im not trying to play tough. But I had a game I used to play with myself, a game called Desert Island and while I was laying around in jail or art class or walking toward the ten dollar window at the track, Id ask myself, Bukowski, if you were on a desert island by yourself, never to be found, except by the birds and the maggots, would you take a stick and scratch words in the sand? I had to say no, and for a while this solved a lot of things and let me go ahead and do a lot of things I didnt want to do, and it got me away from the typewriter and it put me in the charity ward of the county hospital, the blood charging out of my ears and my mouth and my ass, and they waited for me to die but nothing happened. And when I got out I asked myself again, Bukowski, if you were on a desert island and etc.; and do you know, I guess it was because the blood had left my brain or something, I said, YES , yes, I would. I would take a stick and I would scratch words in the sand. Well, this solved a lot of things because it allowed me to go ahead and do the things, all the things I didnt want to do, and it let me have the typewriter too; and since they told me another drink would kill me, I now hold it down to 2 gallons of beer a day.

But writing, of course, like marriage or snowfall or automobile tires, does not always last. You can go to bed on Wednesday night being a writer and wake up on Thursday morning being something else altogether. Or you can go to bed on Wednesday night being a plumber and wake up on Thursday morning being a writer. This is the best kind of writer.

Most of them die, of course, because they try too hard; or, on the other hand, they get famous, and everything they write is published and they dont have to try at all. Death works a lot of avenues, and although you say you like my stuff, I want to let you know that if it turns to rot, it was not because I tried too hard or too little but because I either ran out of beer or blood. [***]

For what its worth, I can afford to wait: I have my stick and I have my sand.

The mention of Frost below alludes to his reciting of his poem The Gift Outright (The land was ours before we were the lands. /(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)) at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy on January 20, 1961 .

[To John William Corrington]

[ca. February 1,] 1961

I am listening to Belly up to the bar, boys! and I took the ponies for $150 today, so what the hell, Cor, I will answer, tho this letter-writing is not my meat, except to maybe gently laugh at the cliffs coming down. And it has to end sometimes, even though it has just begun. Id rather you were the one who finally didnt answer. And Id never kick a man out because he was drunk, although Ive kicked out a few women for it, and the wives-to-pinch, they are gone, mental cruelty, they say; at least the last one, the editoress of Harlequin said that, and I said, ok. my mind was cruel to yours

I think it is perfectly ok to write short short stories and think theyre poems, mostly because short stories waste so many words. So we violate the so-called poem form with the non-false short story word and we violate the story form by saying a lot in the little time of the poem form. We may be in between by borrowing from each BUT BECAUSE WE CANNOT ANSWER A PRECONCEIVED FORMULA OF EITHER STORY OR POEM , does this mean we are necessarily wrong? When Picasso stuck pinches of cardboard and extensions of space upon the flat surface of his paper

did we accuse him of

being a sculptor

or an architect?

A mans either an artist or a flat tire and what he does need not answer to anything, Id say, except the energy of his creation.

Id say that a lot of abstract poetry lets a man off the hook with a can of polish. Now being subtle (which might be another word for original) and being abstract is the difference between knowing and saying it in a different way and not knowing and saying it as if you sounded like you might possibly know. This is what most poetry classes are for: the teaching of the application of the polish, the rubbing out of dirty doubt between writer and reader as to any flaws between the understanding of what a poem ought to be.

Culture and knowledge are too often taken as things that please or do not disturb or say it in a way that sounds kindly. Its time to end this bullshit. I am thinking now of Frost slavering over his poems, blind, the old rabbit hair in his eyes, everybody smiling kindly, and Frost grateful, saying some lie, part of it: the deed of gift was the deed of many warsAn abstract way of saying something kind about something that was not kind at all.

Christ, I dont call for cranks or misanthropes or people who knock knock knock because their spleen has a burr in it or because their grandmother once fucked the iceman, but lets try to use just a little bit of sense. And I dont expect too much; but when a blind blubbering poet in his white years is USED I dont know by WHAT OR WHO himself, they, somethingit ills me even to drink a glass of water and I guess that makes me the greatest crank of all time. [***]

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s»

Look at similar books to Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Living on Luck: Selected letters: 1960s-1970s and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.