The Creator of Oz

by Rebecca Loncraine

Before L. Frank Baum wrote the tale of Dorothys journey from Kansas to Oz, America didnt have a modern fairy tale of its own.

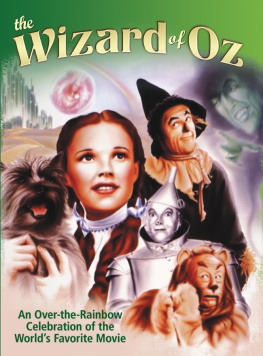

T he movie The Wizard of Oz is so much a part of American culture that we take the storys existence for granted. The twisting tornado that carries Dorothy and Toto from the arid Kansas prairie to the colorful Land of Oz, the clever but brainless Scarecrow, the kind but heartless Tin Man, the brave Cowardly Lion, the Wicked Witch of the West, the humbug Wizard, the Munchkins, the Yellow Brick Road and the Emerald City are all iconic permanently in our collective memories to reference at any relevant moment.

This powerful story seems so old, so universal and so alive that it feels like it must have always been there, rolling around like a shiny, colorful marble at the bottom of our minds.

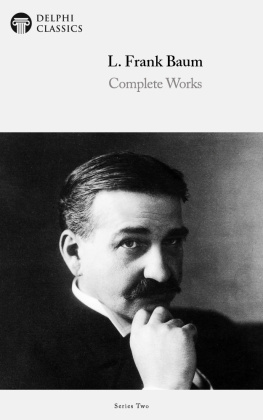

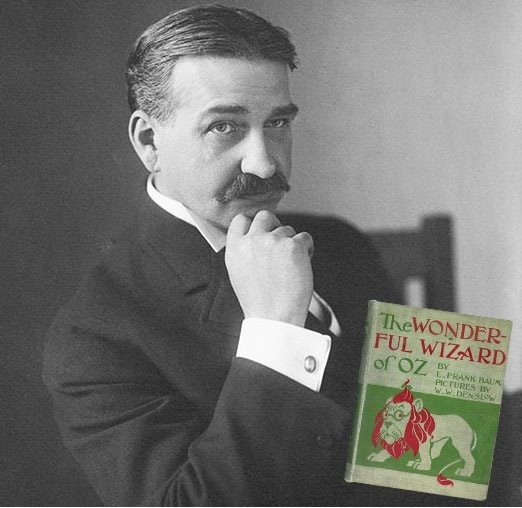

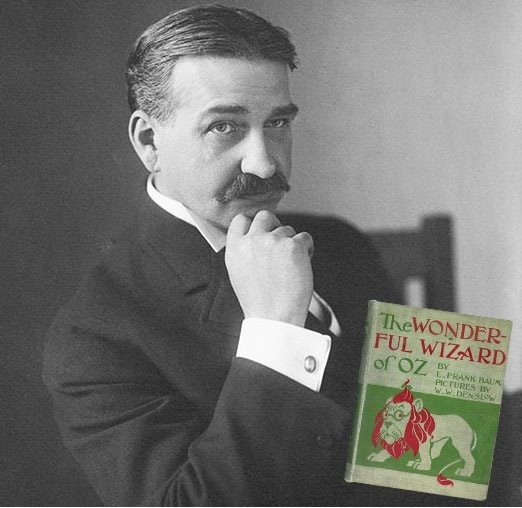

However, the Land of Oz did in fact have a creator. His name was Lyman Frank Baum born in America in 1856. Between the spring of 1898 and the fall of 1899 the story of Dorothy and her friends was conjured from Baums imagination, and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was first published in 1900. Accompanied by bright and beautiful illustrations by William Denslow the book was an immediate hit.

Baum began writing for children later in life, in his 40s, after many years of frustration and dead ends. In the 1890s, before he started writing books, he had tried his hand as a chicken breeder, actor, theater company manager, trinket shop owner, newspaperman, axle grease and china salesman, and designer of elaborate, theatrical department store window displays. Baum was surprised when The Wonderful Wizard of Oz became a bestseller. The books success transformed his life and enabled him to write full time. He went on to write 13 sequels to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz , as well as 50 or so other childrens books under various pen names.

From the successful publication of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900 to Baums death in Hollywood, Calif., in 1919, journalists and readers, bewildered by the creative process of making up stories, would often ask Baum where Oz had come from (child fans, in contrast, wrote to him asking where Oz was located and how they could get there). Baum responded to these questions, characteristically, by making up further stories. Oz had come to him, he said, one day when he looked down at his filing cabinet and saw the drawers marked A-N and O-Z. Humbug. It was easier for Baum to make something up than to admit to probing journalists that he didnt know where the Land of Oz came from.

Baum was right to make up tales about the origins of Oz; we never really know where stories come from. But many of the ideas and themes at work in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz were present in Baums life. Taking a peek behind the curtain to look at the world Baum inhabited in late 19th-century America sheds some light on where Oz came from.

The Writer as Medium

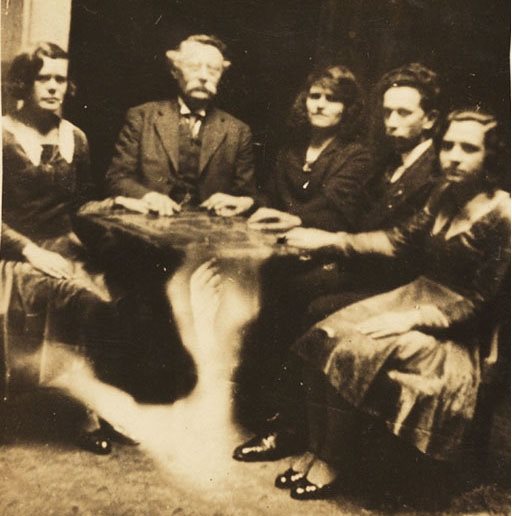

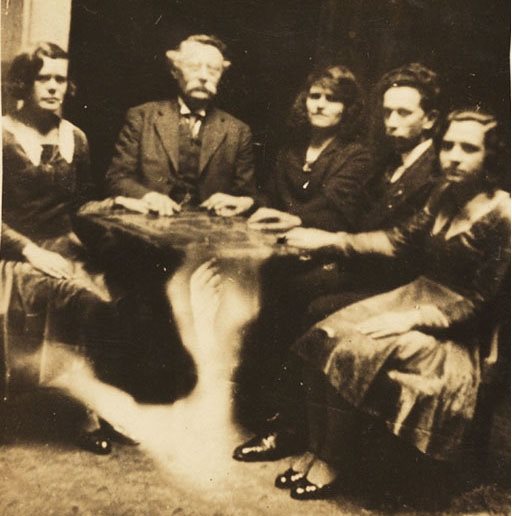

Writing and spirit mediums were very connected in the late 19th century. Spirits were sometimes thought to communicate with the living through writing materials, like the alphabet on a Ouija board. Sisters Margaret, Kate and Leah Fox (pictured at right), famous mediums of the 19th century, communicated with spirits through what were called spirit rappings, much like the language of clicks of the then-new telegraph.

L. Frank Baum took part in a culture of spiritualism that was alive with the knocks, rappings and scribblings of the dead. His wife and mother-in-law sometimes held sances at home. The image of the medium shaped Baums relationship with his own imagination in subtle ways.

When he first began publishing childrens books in 1897, Baum saw himself as a failure. His childrens books were evidence, he wrote to his sister, Mary Louise, of his inability to do anything great. He had tried to make it as a businessman, like his father, but was ill-suited to that world. He found it hard to take himself seriously, either intellectually or creatively, and described himself as a rather stubborn illiterate.

Baum said that the story of Dorothys adventures in Oz simply moved right in and took possession of him. The characters were a sort of inspiration that struck him suddenly; the story really seemed to write itself.

Because Baum saw himself as a medium channeling tales from Oz to America, his characters were absolutely real to him. Frank Jr., Baums eldest son, recalls his father saying that he enjoyed telling stories, because I, too, like to hear about my funny creatures. These characters seem to develop a life of their own. Baum also would say, They often surprise me by what they do.

Baum would sometimes fall into black moods and move about the house restlessly, unable to write, explaining to his wife that my characters just wont do what I want them to.

Baum believed in his characters in the same way that he believed in ghosts. The idea of author as medium served an important psychological function that enabled Baum to write. In understanding his creativity as a form of spirit possession, Baum didnt feel responsible for his stories and therefore he could let his imagination breathe, making space for his intuitive storytelling talent to surface and take hold of his pen.

Child Ghosts

The sunny story of Oz has a dark and gothic dimension. The majority of people in the 1800s, Baum included, believed in ghosts. Tragically, many of these supposed ghosts were of children. One of the influences on Baums young imagination was the deaths of his siblings in infancy. In mid-19th-century America, children under the age of 5 accounted for as many as 40 percent of all deaths.

The infant mortality rate in Baums extended family was unusually high due to a series of diphtheria epidemics across upstate New York that stole hundreds of children away. Four of Baums eight siblings died in infancy, as did at least 10 of his cousins; as a child Baum would have attended numerous funerals of children, usually with the body displayed in an open coffin. These children lived on in the collective imagination of the Baum family, were spoken of often, and continued a kind of shadow life alongside their living siblings.

Baum married Maud Gage and became a father toward the end of the century, when infant mortality had thankfully declined. All four of his sons survived into adulthood, but three of his nieces did not, including Dorothy Gage, who died in 1898 while Baum was writing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz . Maud and Baum longed for a daughter, and his wife was acutely distraught when baby Dorothy died.

Baum was a religious radical, rejecting his Methodist upbringing and following the new cults of Theosophy and Spiritualism. He and Maud joined the Chicago Theosophical Society in 1892. He attended sances, and Maud even hosted some at their home. Spiritualists rejected the Christian idea of heaven and believed in an afterlife they called the Summerland, a place where the souls of the departed could dwell in peace and continue to communicate with the living. Oz was inspired by this reassuring vision; that the Summerland could be imagined as a kind of magical childrens heaven a place where the spirits of children whose lives on Earth had been cut short could have exciting adventures.

Baum and his wife believed in spirits and even hosted sances in their home.

Technological Wizardry

Baum lived in an era of mind-boggling technological invention. He experienced the entrance of electricity into everyday life, the replacement of horses with the horseless carriage and the birth of manned flight. It was truly amazing, frightening and disorienting to be able to switch on an electric light, speak into a telephone, ride in a motor car at a roaring 30 miles per hour and, of all things, fly through the clouds in an airplane. These shocking and exciting novelties transformed the way people understood their world and their bodies. Baum was fascinated by all of the new technologies around him and filled his books with fantastic inventions. But he also wrote into Oz some of his anxieties about the age of invention and what it might be doing to the experience of being human.

Next page