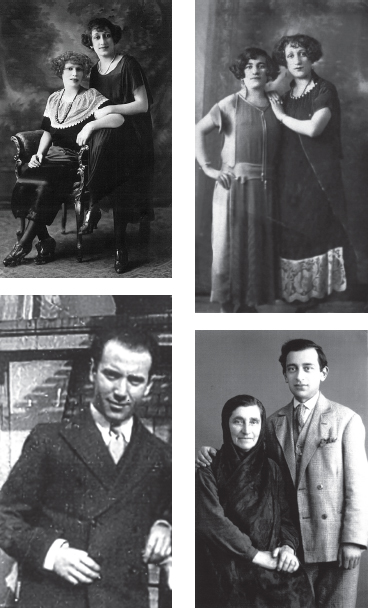

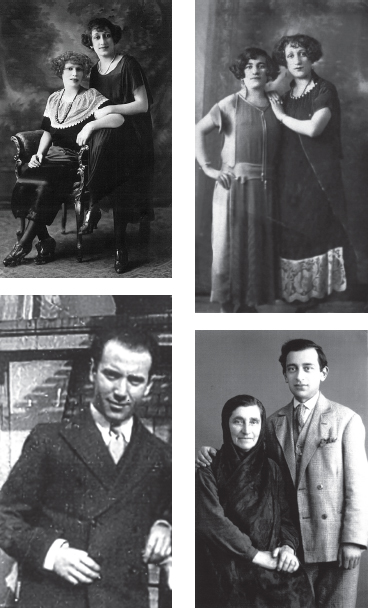

Clockwise from upper left: Mary and Goldie (seated), c. 1917; Mary (on right) and Ray, c. 1926; Hirschel and his mother, c. 1935; Moishe, c. 1938

To my son Avrom:

Here is your grandmother.

Preface

My mother kept no secrets from me about her strange and difficult life before I was born. For most of my growing-up years, she and I lived together in a single furnished room, by a missus, as such living arrangements used to be called. I think our symbiosis was probably much more powerful than the usual between mother and child because most of the time there was no one but the two of us, no other presence to distract or divert. The intensity of my focus on her was compounded, I imagine, because our daily life was played out in the space of no more than ninety square feet. In that tight proximity, she told me things because she had no one else to tell them to. I saw things because she had nowhere else to go and hide. I struggled to understand things because she was my constant care and study and love.

But the older I got, the less I understood. In the glorious hope and brashness of my young womanhood I knew only that the choices shed made, which had brought her, and me along with her, to that lonely, airless furnished room of my childhood, had been incomprehensibly foolish, and that her mistakes would never be mine.

Thirty years after my mothers death, my young-womanhood long gone, a sadness suddenly came upon me with the thought that though Id known all her secrets, I hadnt known her. I think that sadness was triggered because Id been trying to relearn Yiddish, the language I usually spoke with her before I started going to school; and in a book Id bought in order to practice reading in Yiddish, I came upon a lullaby by the writer Sholem Aleichem; it was one I remembered her singing when I was a child.

Bay dayn vigl zitst dayn mameh,

Zingt a lid un veynt.

Vest amol farshteyn mistame

Vos zi hot gemeynt.

I translate it this way:

Near your cradle sits your mother,

Singing a song and weeping.

Perhaps someday youll understand

What her tears meant.

My Mothers Wars is my attempt to understand.

My motherwho was not yet my motherwas kicked out of the home of her half sister Sarah and her brother-in-law Sam several months after she came to America. She was seventeen, and she didnt mind very much being kicked out because by then there was somewhere else shed much rather be living. Of course she couldnt know in 1914 that she would pay dearly, even to the day she died, for Sarah and Sams anger with her. And though I wouldnt be born for many years yet, I would pay, too: I think its fair to say that I grew up in the shadow of my mothers tragedy, which, as things happened, had been made inevitable by what shed failed to do before she was thrown out.

In her shtetl in Latvia, shed seen them only once. That was when Sarah, already a grown woman, came to say goodbye to their father before she and Sam left for America. Mereleh, as my mother was called, was five years old then, and she hid behind der tatehs legs because she felt bashful when the stranger, who looked like a rich gentile lady in a big feathered hat and long white gloves, called her shvesterl, little sister. She was scared too of the man they said was her brother-in-law, though he ignored her as though she were a piece of the scant furniture. He was stiff and thin like a clothespin, with a scraggly pointed beard that wriggled like the one on the goat that had followed her down the street, pulled her little babushka right off her head, and started to eat it. In the next years, whenever der tateh got a letter from his eldest daughter and her husband in America, Mereleh remembered about them only that Sam had frightened her and that Sarah had dragged her from behind der tatehs legs and hugged her to her big bosom so hard that even after their carriage drove away Merelehs cheek bore the indentation of a knob-like coat button.

Yet there she was, twelve years later, living with them in America, sleeping on a Murphy bed in their front room. It had happened because in Latvia, even before Mereleh got her first period, shed been sent out to be an apprentice, first to a milliner and then to a dressmaker, and with loathing shed believed the needle would be her whole life. Then one of the girls with whom she worked at the dressmakers told her about a sister whod gone to New York and was already an actress on the Yiddish stage and getting paid good money for it. That was when Mereleh began to dream. Why not? Shed danced at the Purim festivals in Rezhitse for several years, and every single time, the other dancers stopped to watch her and applaud. Though no one had ever taught her dancing, she knew exactly how to make her movements copy the clarinets moan, the accordions chortle, what to do with her hands, shoulders, legs, hips. After she danced at one Purim festival, a bunch of boys came up to her to tell her she was as graceful as a swan. It was ecstasy for her when she was dancing, like she was in a magical trance. When the dressmaker for whom she worked sent her on an errand and she had to walk through the forest, she even danced there, all alone, humming her own tunes and bowing extravagantly to the tree throngs as though theyd applauded. Why shouldnt she go to America and become a dancer on the stage?

How she convinced der tateh to go along with her plan she could never remember, or at least thats what she told me: she only knew that he begged his oldest daughter and her husband to help her; and that Sam kindly sent money for her passage and gave an affidavit saying that if the authorities would allow her into the country, as her male relative he would take responsibility for her.

Young as she was, my mother realized it was no small thing for Sarah and Sam to bring her to America and give her a place to live and food to eat, and she tried to show she was grateful. Every evening after she ate supper with them at the little table in the kitchen, she carried all the dishes to the sink and washed and dried them and put everything away in the cupboard. On Sunday mornings she gathered up all the dirty sheets, towels, Sams shirts and pants, everyones nightclothes, and she brought them down to the basement where she scrubbed them in the big tub and then carried them up to the rooftop and hung them on clotheslines, and when they were dry she ironed everything that needed ironing. She swept and dusted and washed the kitchen floor, too. No, sister, I really like to, she insisted when Sarah tried to take the mop from her hands and said she didnt have to do so much around the house.

But in truth, she felt awkward with Sarah and Samnot shy as shed been when she was small and they came to say goodbye, but never at ease. It jolted her in the beginning when Sarah introduced her to the neighbors as my sister, because Sarah seemed so old, more like an aunt than a sister, and thered been no chance for sisterly feelings to develop between them. With Sam she was the most uncomfortable. He barely glanced at her and hardly ever said more than good morning to her. She worried that he resented having had to give the affidavit swearing he would be responsible for her. She felt she must get a job right away and start paying him back for all the expense shed been to him.