Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

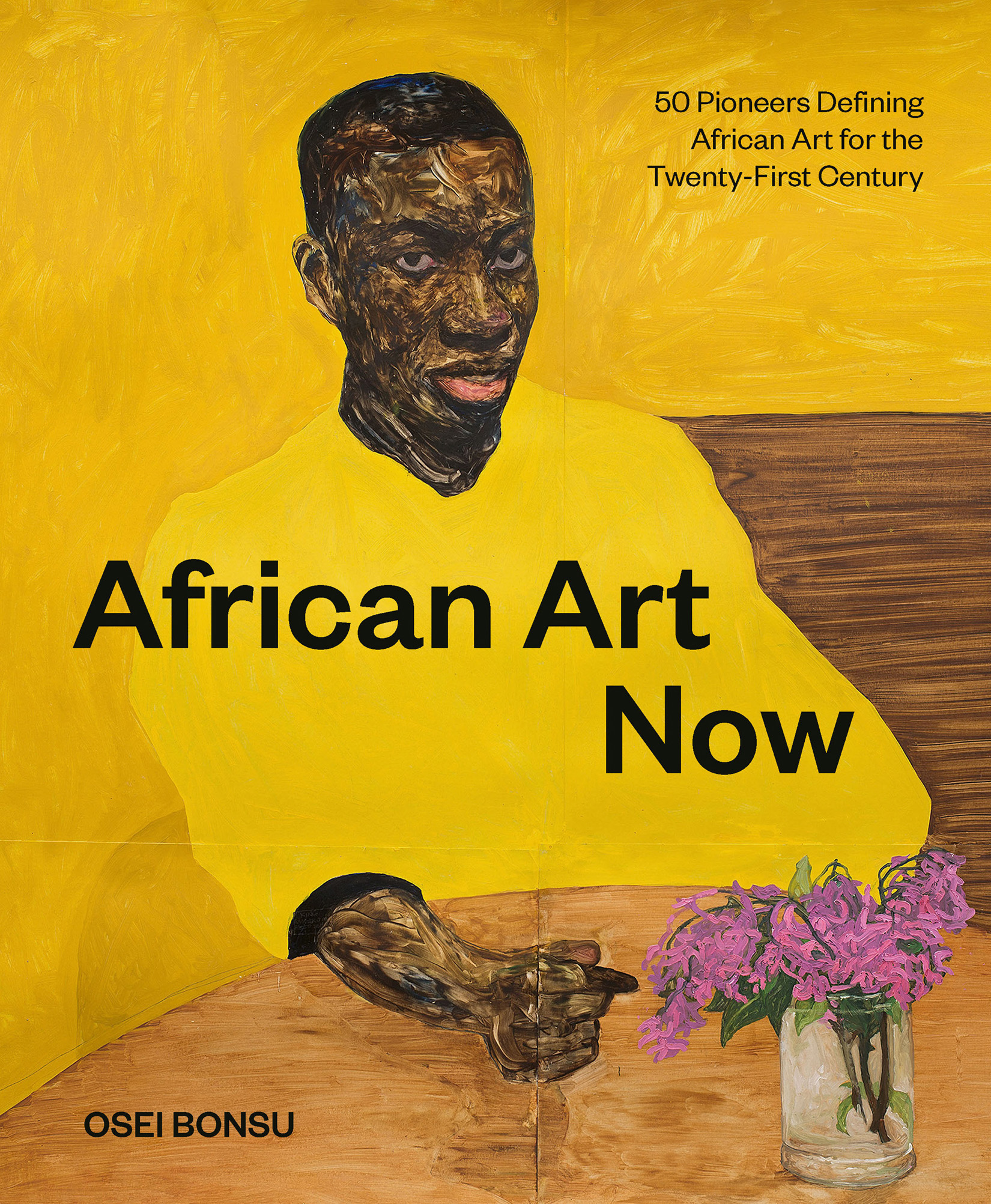

First published in the United States of America in 2022 by Chronicle Books LLC.

First published in the UK in 2022 by

ILEX, an imprint of Octopus Publishing Group Ltd

Octopus Publishing Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DZ

www.octopusbooks.co.uk

An Hachette UK Company

www.hachette.co.uk

Text copyright Osei Bonsu 2022

Publisher: Alison Starling

Commissioning Editor: Ellie Corbett

Managing Editor: Rachel Silverlight

Editorial Assistant: Jeannie Stanley

Art Director: Ben Gardiner

Design: Leonardo Collina

Picture Research: Claire Hamilton

Picture Research Manager: Giulia Hetherington

Senior Production Manager: Katherine Hockley

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Osei Bonsu asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

ISBN 978-1-7972-2101-4 (epub, mobi)

ISBN 978-1-7972-1720-8 (hardcover)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Contents

Foreword Interview: Maro Itoje

Born in 1994 in London, UK, Oghenemaro Maro Miles Itoje is an English professional rugby union player who is championing African art and highlighting the need for a balanced curriculum that teaches students about Black history. In 2021 he co-curated the exhibition A History Untold , celebrating the contributions of Black artists and thinkers throughout history.

Osei Bonsu: Growing up between British and African cultures, as we both did, you became distinctly aware of the importance of being rooted in your identity and how it ultimately shapes the person you become. You grew up in a Nigerian household, where Im sure you were exposed to West Africas rich visual culture, but what was that first encounter with art?

Maro Itoje: For me, it really came alive around about 2015, when I was moving into my first apartment and I wanted to design it with some African art. I was looking around to see where I could go in London, and I couldnt really find anywhere, and the very few places I did find at that time were way out of my budget. I brought this dilemma to my mom, who told me, dont worry, when we go back to Nigeria, well go to the art market there and then youll be able to get what you need.

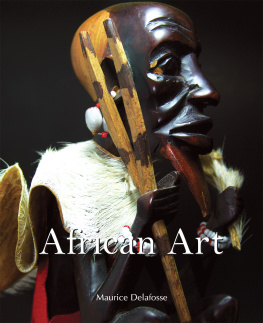

When the time came, I went back to Nigeria and I was taken aback by all the different forms, styles, the colour, the dynamism, the texture, the vibrancy of all the art pieces. This might be born of being a child of the British-Nigerian, or Nigerian-British diaspora, but I felt a connection to the art pieces that I didnt feel with European pieces Id seen more commonly growing up. I felt as if I had a connection to it with my soul and that it better reflected me as an individual. Ever since then, my passion for African art has grown and grown.

OB: Your career in rugby meant you ended up attending different schools and engaging with people from different cultural and social backgrounds. The history of how Black people came to be part of British society, from the transatlantic slave trade to modern migration, is rarely taught in schools here in England. Youre passionate about increasing the awareness of Black history in education when did this become a priority for you as a public figure?

MI: I was probably conscious of it during sixth form, but it became more obvious to me when I moved to university. I had an English lecturer and tutor who was an expert in African studies and African politics. I was listening to him talk about Nigeria and I found it a little bit weird that this English guy knows way more about Nigeria than me. Obviously Im not going to know more about Nigeria than everyone, but I found it a little bit uncomfortable in that I dont actually know much about the history of the place that Im from.

It took conscious learning for me to pick up on some of those issues. While I cant complain about my education in a lot of respects, it does paint a single narrative with regard to Black history or African history; it paints a picture which doesnt encapsulate the whole story.

OB: Im sure there was a pantheon of sports stars you admired and followed in your youth, but, growing up, were there any particular cultural or artistic figures that you followed?

MI: Especially when I started looking into history a bit more, one of the figures that to this day I incredibly admire is Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana.

OB: As a Nigerian, it must be hard to say that one of your biggest heroes is a Ghanaian [laughs] .

MI: [laughs] No, no, I think he was brilliant. I thought the way he fought for Ghanaian independence, his values, his morals, the way he stood for a united Africa, the self-empowerment, I think hes a phenomenal man. Even the people I look up to in sports, the ones I truly admire, they always stand for something which is greater than the sport that they compete in.

One of the best examples of that is Muhammad Ali. Not only was he arguably the best boxer to have ever lived, but he also was a champion of equality, of Black rights; he was pivotal to the civil rights movement and Black empowerment and being an example of Black excellence.

OB: One of the enduring legacies of Ghanas first president Kwame Nkrumah today is still this idea of pan-Africanism, as an ideology that embraces unity across the continent and African peoples around the world. In many ways, this book seeks to represent a broad image of African art today, one which embraces multiple African identities, histories and cultures. As a collector, I wondered if you were starting to see certain connections between artists you admire. How would you define your interest when it comes to art?

MI: Good question. Initially when I first started collecting art, it was purely from an aesthetic point of view. As the first couple of years went by, I realised that there was a trend in the art that I was buying: all these pieces were of strong African women. For me, there is something in particular with African art, especially Nigerian art, with the way they depict women. They depict them as proud, striking, vibrant figures and I think subconsciously that was something that really connected with me.

After a while, I was like, my house cant be full of all women [laughs] , I need to balance it out a little bit. I started to get into more abstract work, plus some more pencil drawings. From my experience of African art, there is a real 3D dimension to it: there are objects that flow off the canvas, or you can feel the roughness and the edge to the pieces in comparison to what Ive seen in other forms of art.

OB: Since you presented the exhibition A History Untold at the Signature Art Gallery in Londons Mayfair in 2021, Im sure youve been asked about your impressions of the art world. What excites you about the African art scene today?

MI: I feel as if African art is the category of art that has the most room to grow. Until the last couple of years, I dont think African art has been fully appreciated on a global scale. Were now seeing more and more, both in popular culture and also in art institutions, art auction houses, art galleries, that the value in African art is being seen. Galleries are beginning to represent more African artists, have more of their pieces and sell more of their pieces. Ultimately thats a good thing for the artists, a good thing for Africa and a good thing for the whole art scene.