INTRODUCTION

Cinema is not set in stone. No aspect of the medium is completely immutable, least of all color. Dialogue can be bleeped or re-dubbed, and soundtracks can be swapped in or out to accommodate music licensing rights. Plot can be chopped up by the almighty rewind and fast-forward buttons, or by the hordes of autodidact video editors cutting together fan tributes on YouTube and social media. Reformatting a film for broadcast on TV, home-video release, or aeroplane seatback screens can stretch the aspect-ratio rectangle to haunted-house-mirror proportions. But the change in color is all but inevitable, a function of times onward march rather than deliberate creative intervention.

If not properly tended, a filmstrip will fade or be subject to other discoloration, as its blacks turn maroon or a wash of red tints the frame. In the movie theaters designed to set the standard for technical presentation, incorrect lensing on the projector can dim the brightness, not so differently from the warming and cooling color settings on a TV. Computerized storage doesnt guarantee fidelity eitherthe processes of screenshotting and jpeg-pasting as susceptible to deterioration as physical preservation. Digital projection will not produce the same texture and hue as its analogue forebears on 35mm reels or the bigger and bolder 70mm; which of them can be said to be the true color of the work at hand?

Type any search for a specific shot into Googledoor scene Titanic provides a shared frame of reference for us alland youll find an array of color-warped versions of the same image. Jack clings to Rose as he sinks into the icy Atlantic, a navy blue filter overlaid to communicate the sub-zero temperatures. In another, the light levels on the dark blues have been turned up so that we might luxuriate in every last detail of a young Leonardo DiCaprios face. Another result does away with the blue entirely, highlighting the off-white and cream tones in Jacks shirt and Roses lifejacket. Keep scrolling, and a saturated version plays up the red of Roses hair, a storybook luster to go with the impossible romance. After no more than a few minutes, it gets harder to recall which one is right: the one you remember from the endless theatrical run or the two-cassette VHS set you had in your youth. With enough distance from experience, memory becomes the final stage of recoloring.

A fickle, indefinite thing, color, and yet a crucial one. A well-placed red or green can dictate tone or plant symbolic meaning, establish a location or time (both for the setting and the period of its real-world production), identify characters as heroes or villains. We can chart shifting social mores in the gradually purpling hue of prop blood, or the contrast of light on Black actors skin. The book in your hands proffers an incomplete survey of all that color can do and be in cinema, approaching the topic both as a concept deployed in the artistic process and as a tangible quantity fabricated by professionals at the forefront of their fields. Tackling such a broad subject requires a combination of technical explication to break down the nitty-gritty answers to the question of how, deep-tissue criticism to get to the heart of why, and cohesive history to put it all together in the context of an ongoing narrative. The evolution of color is the evolution of cinema itselfan equipment-forward business, an art form, and an extension of the society creating it.

Color lends itself to an uncommonly linear story in the way each revolutionary advance supplants the last one. This books four sections have been divided up along these lines, with the first part taking us from the inception of moving pictures to the heyday of Technicolor, the second running up to Technicolors demise, the third addressing the videotape era, and the fourth sifting through the mass digitization that brings us to the present. We can see other global developments playing out within this framework, as cheapening film stock brought color cinematography to emergent national movements, while competition between consumer-grade giants Kodak and Fujifilm gave amateurs state-of-the-art tools. Color provides a ready bellwether for change on the macrocosmic level, each new breakthrough of brilliance reflected in a look unique to its moment.

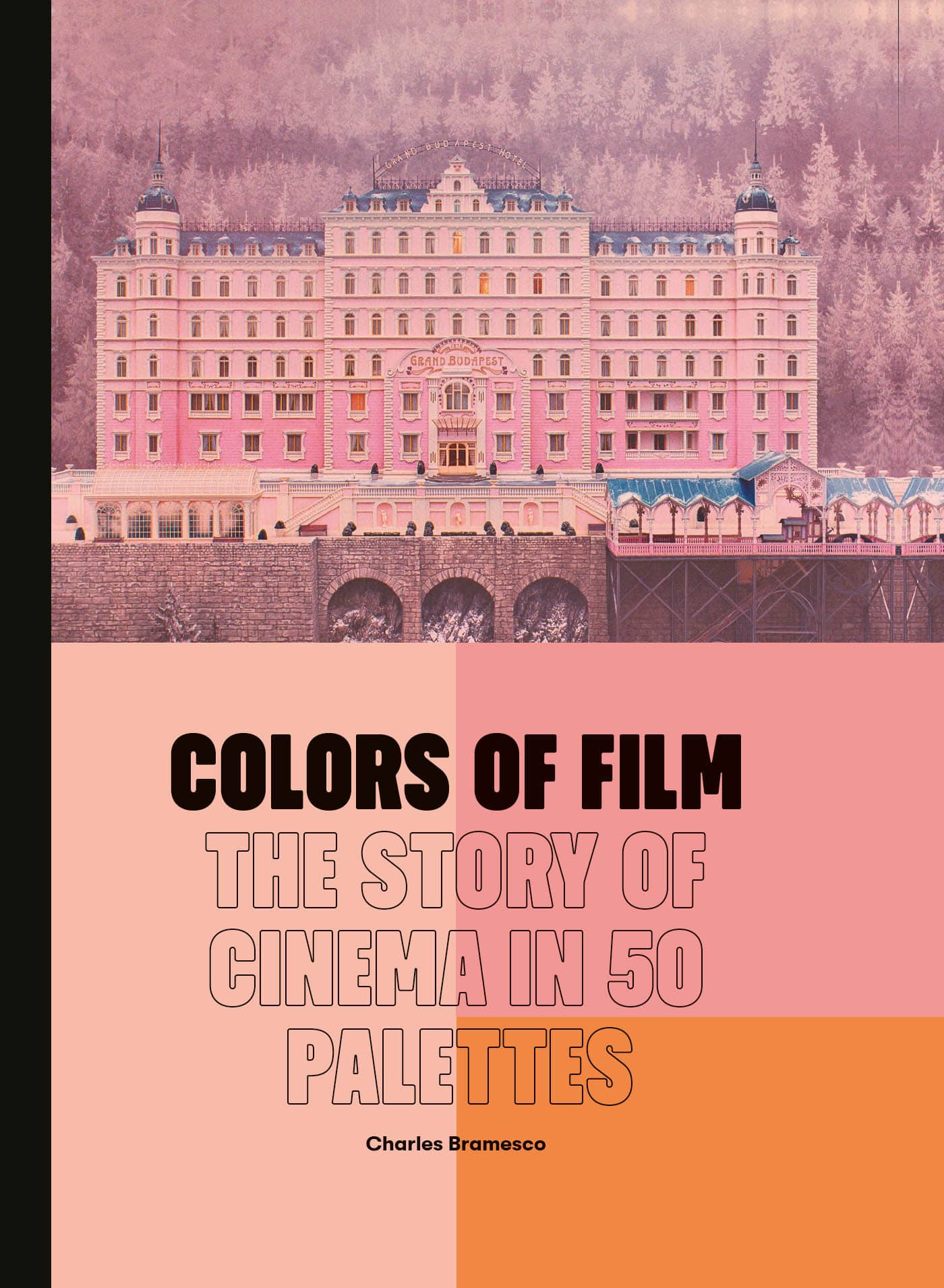

Even within something as subtle and aesthetically pure as color, theres still an embedded politics, sometimes explicit and sometimes buried in subtext. A genius in his final days adopts blue as a figurative and literal way of seeing the world, as well as an act of protest; a queer satire mocks retro notions of femininity by turning up the pink until its garish enough to serve as a parody of itself; in a developing Senegal, the tension between local heritage and colonialist interference plays out in the contrast between organic and manmade colors. Cinema deals in visual information, with reams of commentary and subjectivity encoded in curtains, a shirt, or other unobtrusive detritus of the everyday. Color is the perfect hiding place for significance, most powerful when left unstated.

But for all its versatility as metaphor, color can also be a presence unto itself, as expressive and tactile as any actor. Avant-garde cinema and the mainstream relatives sampling its hallucinatory un-logic may place swirls of abstract color in place of character and dialogue, overriding storytelling and going straight to visceral building of a mood. For this, we may have Walt Disney to partially thank, his finest hour being a feature-length tribute to the raw magnificence of color and sound in its most unadulterated form. He saw that color wasnt just one more way to make the light dancing on the silver screen closer to reproducing our sense of sight, but an infinitely malleable force that can be translated to violence, disorientation, or love.

On relevance over bottom-line quotient of genius, weve compiled a curriculum of fifty films that attempt to explore the full potential of color, both in spectrum and application. Although I personally must cop to a somewhat Hollywood-centric mindset as an American, the titles selected for this book were chosen for variety, straining to cover the full breadth of the medium across nations, eras, genres, industry scale, and subject matter. With one notable exception, black and white films have been excluded for lack of pertinence and the sake of organization, although another book could be written on the painterly interplay of light and shadow that makes up a monochrome composition. To this same effect, we could easily have rounded up fifty documentaries raising an entirely different set of philosophical enquiries, a conversation too rich and dense to be confined to one or two picks.

Within this curriculum, groups of films may be cognitively lumped together to form miniature lesson plans. A trio of clown-colored musicals spanning the Atlantic Ocean and the better part of a century collectively illustrate how influence begets homage and deconstruction. The digital age section can be boiled down to three action epicsone favoring practical effects, one all computerized, and one an innovative mix of bothin which heroes zip around futuristic landscapes at breakneck speeds in souped-up vehicles too rad to be real. An essential 1950s melodrama gains a companion piece in a loose remake twenty years later. Two portraits of tormented womanhood use radically dissimilar palettes to make comparable statements about the hardships of compulsory heterosexuality. Ideally, the chronological arrangement of the entries will build an expanding bank of knowledge that primes cinephiles and lay readers alike to digest each successive chapter, and with time, each new film they watch.