THERE was a wall. It did not look important. It was built of uncut rocks roughly mortared. An adult could look right over it, and even a child could climb it. Where it crossed the roadway, instead of having a gate it degenerated into mere geometry, a line, an idea of boundary. But the idea was real. It was important. For seven generations there had been nothing in the world more important than that wall.

Like all walls it was ambiguous, two-faced. What was inside it and what was outside it depended upon which side of it you were on.

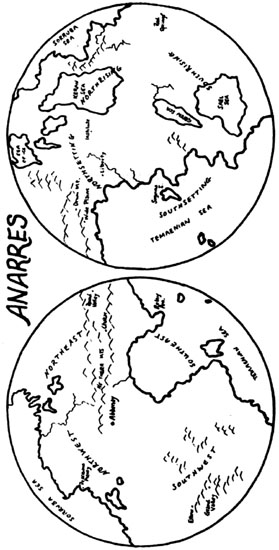

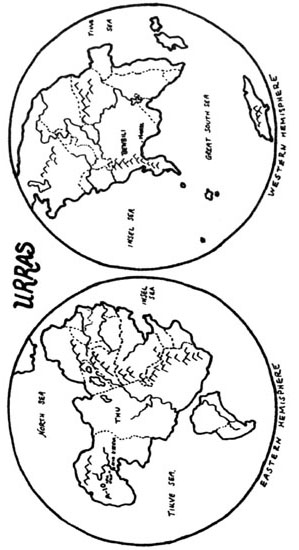

Looked at from one side, the wall enclosed a barren sixty-acre field called the Port of Anarres. On the field there were a couple of large gantry cranes, a rocket pad, three warehouses, a truck garage, and a dormitory. The dormitory looked durable, grimy, and mournful; it had no gardens, no children; plainly nobody lived there or was even meant to stay there long. It was in fact a quarantine. The wall shut in not only the landing field but also the ships that came down out of space, and the men that came on the ships, and the worlds they came from, and the rest of the universe. It enclosed the universe, leaving Anarres outside, free.

Looked at from the other side, the wall enclosed Anarres: the whole planet was inside it, a great prison camp, cut off from other worlds and other men, in quarantine.

A number of people were coming along the road towards the landing field, or standing around where the road cut through the wall.

People often came out from the nearby city of Abbenay in hopes of seeing a spaceship, or simply to see the wall. After all, it was the only boundary wall on their world. Nowhere else could they see a sign that said No Trespassing. Adolescents, particularly, were drawn to it. They came up to the wall; they sat on it. There might be a gang to watch, offloading crates from track trucks at the warehouses. There might even be a freighter on the pad. Freighters came down only eight times a year, unannounced except to syndics actually working at the Port, so when the spectators were lucky enough to see one they were excited, at first. But there they sat, and there it sat, a squat black tower in a mess of movable cranes, away off across the field. And then a woman came over from one of the warehouse crews and said, Were shutting down for today, brothers. She was wearing the Defense armband, a sight almost as rare as a spaceship. That was a bit of a thrill. But though her tone was mild, it was final. She was the foreman of this gang, and if provoked would be backed up by her syndics. And anyhow there wasnt anything to see. The aliens, the offworlders, stayed hiding in their ship. No show.

It was a dull show for the Defense crew, too. Sometimes the foreman wished that somebody would just try to cross the wall, an alien crewman jumping ship, or a kid from Abbenay trying to sneak in for a closer look at the freighter. But it never happened. Nothing ever happened. When something did happen she wasnt ready for it.

The captain of the freighter Mindful said to her, Is that mob after my ship?

The foreman looked and saw that in fact there was a real crowd around the gate, a hundred or more people. They were standing around, just standing, the way people had stood at produce-train stations during the Famine. It gave the foreman a scare.

No. They, ah, protest, she said in her slow and limited Iotic. Protest the, ah, you know. Passenger?

You mean theyre after this bastard were supposed to take? Are they going to try to stop him, or us?

The word bastard, untranslatable in the foremans language, meant nothing to her except some kind of foreign term for her people, but she had never liked the sound of it, or the captains tone, or the captain. Can you look after you? she asked briefly.

Hell, yes. You just get the rest of this cargo unloaded, quick. And get this passenger bastard on board. No mob of Oddies is about to give us any trouble. He patted the thing he wore on his belt, a metal object like a deformed penis, and looked patronizingly at the unarmed woman.

She gave the phallic object, which she knew was a weapon, a cold glance. Ship will be loaded by fourteen hours, she said. Keep crew on board safe. Lift off at fourteen hours forty. If you need help, leave message on tape at Ground Control. She strode off before the captain could one-up her. Anger made her more forceful with her crew and the crowd. Clear the road there! she ordered as she neared the wall. Trucks are coming through, somebodys going to get hurt. Clear aside!

The men and women in the crowd argued with her and with one another. They kept crossing the road, and some came inside the wall. Yet they did more or less clear the way. If the foreman had no experience in bossing a mob, they had no experience in being one. Members of a community, not elements of a collectivity, they were not moved by mass feeling; there were as many emotions there as there were people. And they did not expect commands to be arbitrary, so they had no practice in disobeying them. Their inexperience saved the passengers life.

Some of them had come there to kill a traitor. Others had come to prevent him from leaving, or to yell insults at him, or just to look at him; and all these others obstructed the sheer brief path of the assassins. None of them had firearms, though a couple had knives. Assault to them meant bodily assault; they wanted to take the traitor into their own hands. They expected him to come guarded, in a vehicle. While they were trying to inspect a goods truck and arguing with its outraged driver, the man they wanted came walking up the road, alone. When they recognized him he was already halfway across the field, with five Defense syndics following him. Those who had wanted to kill him resorted to pursuit, too late, and to rock throwing, not quite too late. They barely winged the man they wanted, just as he got to the ship, but a two-pound flint caught one of the Defense crew on the side of the head and killed him on the spot.