Sometimes, I feel the past and the future pressing so hard on either side that theres no room for the present at all.

Obviously Im into myself, but Im not walking around just saying, Oh, everybody look at me. I wear make-up and dress this way because it makes me look better. Im not doing it to get people to stare at me. If I wanted to do that, I could just put a pot on my head, wear a wedding dress and scream down the high street. Its easy just to get attention. People also think if you look like this, youre running away from something Im not hiding. Its a long way from hiding.

BOY GEORGE

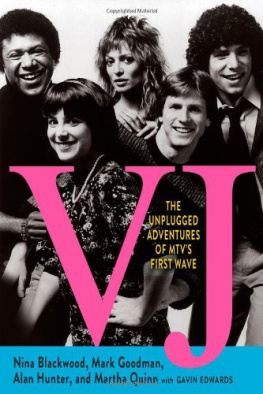

Who were all these people?

It was late March 1979, a Tuesday night, around ten thirty, and Covent Garden was dark, wet and ominously quiet. The street lights were off, there were no cars, no bodies. It was springtime, but still cold and empty, looking not unlike the set of some fifties spy movie one of the austere black-and-white ones, before James Bond and Harry Palmer came bounding in with their smirks and their colourful ironic cool. The Winter of Discontent may have just drawn to a close, with the dustmen finally going back to work, but the central London streets were still full of rotting rubbish, with food scraps spilling out of the sodden cardboard boxes, cracked plastic containers and torn black bin liners dumped by the neighbourhood restaurants. Five years ago, the famous fruit and vegetable market had moved south, over the Thames to Nine Elms, taking any hustle and bustle along with it, and the new shopping centre in the Covent Garden piazza was still over a year away (the new arcade development would have quaint, old-fashioned gas lamps at the request of the architect). So Covent Garden still felt very much like a postcode in limbo.

Tonight, though, at the eastern end of Great Queen Street, near Kingsway, a crowd of extravagantly attired night owls was gathering outside a small, nondescript wine bar, some of them clogging up the pavement in their shawls and funny-looking capes, their hairstyles making several appear far taller than they actually were, rivalling the unlit street lamps for attention in the moonlight. Their stilettos and brogues may have been wet from the puddles, but they all looked polished. There was someone who looked a little like a young Clark Gable, another wearing black leggings and a skirt under his black Lewis Leathers jacket. Others were sporting metallics and neon.

Squeezed next to a tiny secretarial agency, from the outside the Blitz looked completely unprepossessing, almost as though it was daring you to ignore it. A small sign inside asked you to keep the noise down as you left, out of respect to the local residents, although it was difficult to see where they might have lived.

To the uninitiated the place just looked like any other wine bar.

It was the people, though, who appeared to make the Blitz what it was. One by one, they slowly filed into the club, passing by the concertinaed metal grille across the front and nodding to the doorman, who appeared to be just as extravagantly dressed as they were. Actually, he seemed far more important than a doorman often acknowledging someone he knew, and even occasionally asking someone to step aside, usually the least extravagantly dressed. Tonight, he was dressed in some weird leather jodhpurs and a massive German overcoat. Im strict on the door because once people are inside I dont want them to feel they are in a goldfish bowl, he would say, when asked by the papers. I want them to feel they are in their own place, amongst friends.

And there were so-called friends everywhere. Covent Garden might have been desolate and badly lit, but then you walked into the club and it was suddenly, Ta-da!

The reason they were all here was because Steve Strange the abundantly attired doorman and Rusty Egan the DJ had decided to move their regular Bowie night at Billys a club way over in Soho to a more hospitable venue. The Blitzs manager, Brendan Connolly, had apparently been struggling to fill the club towards the start of the week, and so took a gamble on the Billys crowd. But they were all here tonight, as they were every week, as were the press, who had started to take notice too, calling them the Peacock Punks, the Cult with No Name or worse New Romantics.

Once inside, the Blitz actually looked a bit seedy, almost as though it hadnt been decorated since well, since the Blitz. The Second World War-style austerity echoed the flatlining seventies: bare floorboards, gingham tablecloths, old film posters, a bit of wood panelling, an overhead fan, pendant lights with dusty enamel shades, and the obligatory framed pictures of Churchill. There was a small blackboard All Blitz cocktails 1.95 with a hastily drawn martini glass, complete with its own olive. There were even some old gas masks.

The people were glamorous, though. A lot of them and there was almost no one over the age of twenty-five looked like theyd come straight from Central Casting, extras in their very own movie. There was a girl over there with cascading copper-red hair, dressed up to look like Rita Hayworth if Rita Hayworth had been wearing a silver spray-on cocktail dress and S&M stilettos, that is. Indeed, some of the girls were in such tight dresses they looked like egg timers. One had such defined cheekbones they appeared to be almost swollen.

Chatting over by the bar were Steve Dagger, the super-slick manager of Spandau Ballet (who would soon become the Blitzs in-house band); Robert Elms, who was the scenes most reliable Boswell; Fiona Dealey, a St Martins fashion student and generally regarded as one of the queens of the Blitz; Chris Sullivan, soon to form a short-lived jazzsalsa band called Blue Rondo la Turk; milliner Stephen Jones; fashion student Michele Clapton, who would one day become an Emmy-winning costume designer, working on Game of Thrones; and Cerith Wyn Evans, another St Martins boy, who would go on to win the Hepworth Prize for Sculpture. So many people in this room would go on to become something or other, but for now they seemed content to pose about in their satin and tat.

Over in the corner was the society photographer Richard Young, who had descended into Covent Garden tonight, forsaking the bold-face names at Tramp, the Embassy and the Dorchester. For him, there were rich pickings here. Everyone was dressed up as though their lives depended on being photographed, swishing and pouting and looking almost like mobile sculptures. They smiled, they glowered, they knew they were in exactly the right place at the right time.

As you passed the cloakroom, youd see a seventeen-year-old George ODowd, who in a few years would be known as Boy George. Ostensibly he was here to check coats, although there was always a suspicion he rifled through the pockets when everyone was on the dancefloor. He already had the razor-blade wit that would stand him in good stead when he was being besieged by the worlds press in a few years time: Doing that one to death, arent you, darling? he would say, if he thought you hadnt been adventurous enough with what you were wearing. People tried to avoid the cloakroom as much as possible.

Sitting in a huddle at one of the small, rickety, gingham-covered tables around the edge of the club were a couple of them, the small nucleus of London archy-farties who until the Blitz Kids arrived were the crowd who populated the paparazzi pages in Ritz magazine: Andrew Logan, Duggie Fields, Zandra Rhodes and Peter York, one of the greatest social chroniclers of our time, and someone who