Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

We pressed against

The limits of the sea:

I saw there were no oceans left

For scavengers like me.

I made it to the forward deck

I blessed our remnant fleet

And then consented to be wrecked

A thousand kisses deep.

Leonard Cohen, A Thousand Kisses Deep

Now fisheries experts speculate on the possibility and the probability of literally farming the ocean. These experts talk of huge undersea fish ranches where fish are herded like cattle and fenced in by curtains of air-bubbles, and of artificial water-circulation techniques being used to increase plankton productivity. It takes only a lively imagination to envision whole cities under the sea.

From the U.S. Department of the Interior Annual Report, 1970, quoted in From Abundance to Scarcity: A History of U.S. Marine Fisheries Policy by Michael L. Weber

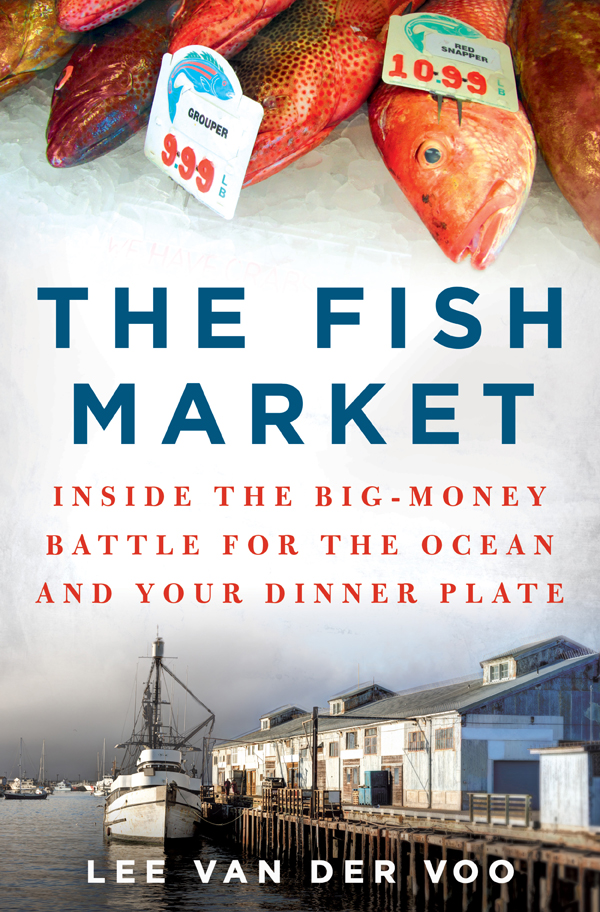

T HIS BOOK IS THE PRODUCT of a lost bet. Thats the truth. In winter 2011, I had just written a story for a regional magazine about salmon fishing. And I was in a bar in Portland, Oregon, a wood-paneled place downtown called Cassidys, loudly proclaiming that I was never going to do it again. Fish stories are boring, I said. Nobody reads them. Theres nothing in them but a bunch of fishermen haggling over who gets to catch what.

I was with a small group of writers, most of whom agreed by glazing over. See what I mean? I thought. But there was one exception. A colleague had just taken a job with the nonprofit group Ecotrust and bet me on the spot that he could get me to write another fish story. Then he started telling me that the United States was privatizing its oceans through a policy called catch shares. And that, while the work was dovetailing with a lot of foodie-centric and eco-conscious buzzwords, it was also creating class warfare on the seas, upending fishing families and unmooring fishing towns all over the nation. His was one of a handful of groups brewing antidotes to the fallout. The more he talked, the more I knew Id lose the bet.

I was doing a lot of food and sustainability writing at the time, so the idea of goofy policy hiding behind eco-friendly jargon wasnt exactly new. To a journalist, greenwashing was the consumer plague of the millennium, amping up while organic food shifted from back-to-the-land hippies to the mainstream. By then, organics were a $25 billion industry in the United States, one in which fair-trade and environmentally conscious brands were garnering a premium from people dining on a do-no-harm ethos. Consumers who didnt want their eggs laid by caged chickens or their beef culled from penned cows were easy marks. I was already covering an enormous number of bunk-but-presumably-green-leaning food and product schemes. And given that the seafood counter was the place inside the grocery store where people looked the most lost, it seemed like a reasonable venue for a hoodwinking.

I was lucky the wager was only beer. A few months later I was on a plane to Alaska with loose orders from an editor to go sniff around. In between, Id managed to get a handle on what catch shares were. The quick way to describe them is to say theyre like cap-and-trade for fish; they deploy caps on the amount of fish that can be caught, then dole out the rights to fish them among qualifying entities. Those who qualify can be fishermen, boats, corporationsthe design varies. It takes some history in the industry to get a piece. But once those rights are awarded by the government, whoever holds that slice of the pie holds exclusive access to a corresponding percentage of fish. Those rights are privately controlled after that. By law, the government can take them back at any time. But it hasnt. Every catch share in America has remained steadily in private hands since 1992. Now the rights to catch fish are private market assets that trade hotter in places like Alaska than brick-and-mortar real estate.

Promoters of catch shares are always quick to say that theyre not privatizing the fish in the ocean, just the rights to catch them. Its a small distinction that translates, in practice, to the same thing. But the delicate public relations dance that attends that particular point has been whirling for the better part of a decade in America. For good reason, Ive surmised. There is a strange marriage at the heart of this policy: one between the environmental lobby and privatization interests. And the effort, though well intentioned by many within organizations like the Environmental Defense Fund, has been substantially funded by conservatives and property-rights promoters, chiefly the founders of Walmart, facts that would give anybody with enviro cred pause if they were better known.

Before I went to Alaska, I spent two days in Oregons Rogue Valley with a man named John Enge, a fisheries expert who ran a seafood-politics blog called Alaska Cafe. He was a saint of a person who is no longer with us. He sat me at his kitchen table and patiently brain-dumped at me until I understood three things: First, the private property rights attending catch shares had locked many fishermen and even whole communities out of the oceans. Second, catch shares had created powerful landlords on water. And third, as those landlords grew more powerful, catch shares were converting fishermen from proud family-business sorts into sharecroppers who were leasing their access to the sea from wealthy and increasingly corporate power brokers.

That was in 2012. What Id envisioned was a quick jaunt to Alaska and a handful of stories. Instead, my trip turned into a four-year reporting odyssey that ended, back in Alaska, in the bunks of a fishing boat with a couple of twenty-something dudes. In between, I learned that I do indeed get seasick. And that a careful regimen of non-drowsy Dramamine, vanilla yogurt, and green-yellow Gatorade keeps it to a no-fuss affair. I also traveled to every catch share in America to walk the docks and talk to fishermen about how catch shares had changed their world. Some were kind enough to take me fishing and show me how that world worked. For context, I spent countless days in the fluorescent-lit meetings of US fishery management councils, the regulatory bodies that control commercial fishing in America. And I talked to chefs and fishermen, seafood buyers and suppliers, conservation groups, lobbyists, and political sorts, many of whom believed very deeply in catch shares. I learned there is a decent business case for privatizing the oceans. And that, while it can conflict with the social-equity ideas that many eco-conscious eaters go in for, it may be one that consumers find quite valid.

After years of staring at it, Ive come to think of this as a David-and-Goliath kind of tale. Its about the fight between seafarersthose who held out against privatizationand powerful conservationists who were willing to trade privatization for both environmental gain and the most sustainable, traceable seafood in the world. It is a story full of grizzled, off-beat characters; action and adventure on the vast oceans off Americas shores; good food; and big, big money. It caused me to see fishermen as just a particularly colorful brand of organic farmer. And catch-share holdouts as the only resisters to the denationalization of a natural resource most Americans believe they still own.