The Bee People

by

Margaret Warner Morley

Yesterday's Classics

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Cover and Arrangement 2010 Yesterday's Classics, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

This edition, first published in 2010 by Yesterday's Classics, an imprint of Yesterday's Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by A. C. McClurg & Company in 1914. This title is available in a print edition (ISBN 978-1-59915-318-6).

Yesterday's Classics, LLC

PO Box 3418

Chapel Hill, NC 27515

Yesterday's Classics

Yesterday's Classics republishes classic books for children from the golden age of children's literature, the era from 1880 to 1920. Many of our titles are offered in high-quality paperback editions, with text cast in modern easy-to-read type for today's readers. The illustrations from the original volumes are included except in those few cases where the quality of the original images is too low to make their reproduction feasible. Unless specified otherwise, color illustrations in the original volumes are rendered in black and white in our print editions.

Introduction

Bees and flowers belong together. We cannot understand the one without the other. For, you see, bees get their food from the flowers, and the flowers need the bees to enable them to form their seeds.

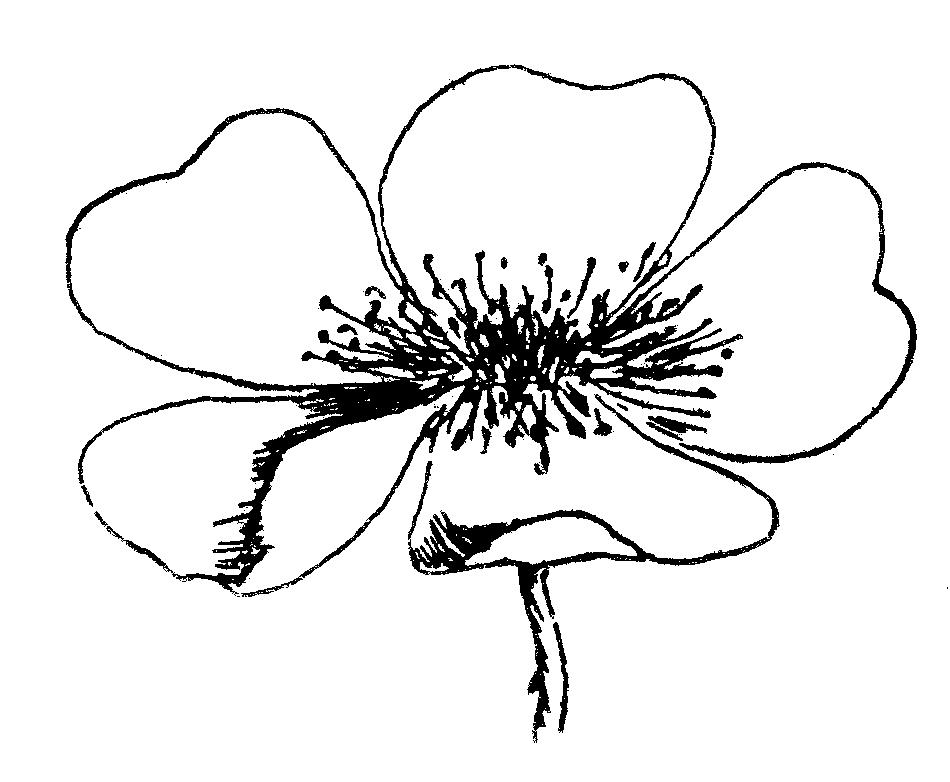

The flowers that we like best have bright-colored petals. The petals of a rose are pink or white or yellow. The petals of a violet are purple, and those of a forget-me-not are blue.

Sometimes the petals are separate, as in a rose or a buttercup, and you can pull them off one by one.

THE WILD ROSE WITH FIVE SEPARATE PETALS

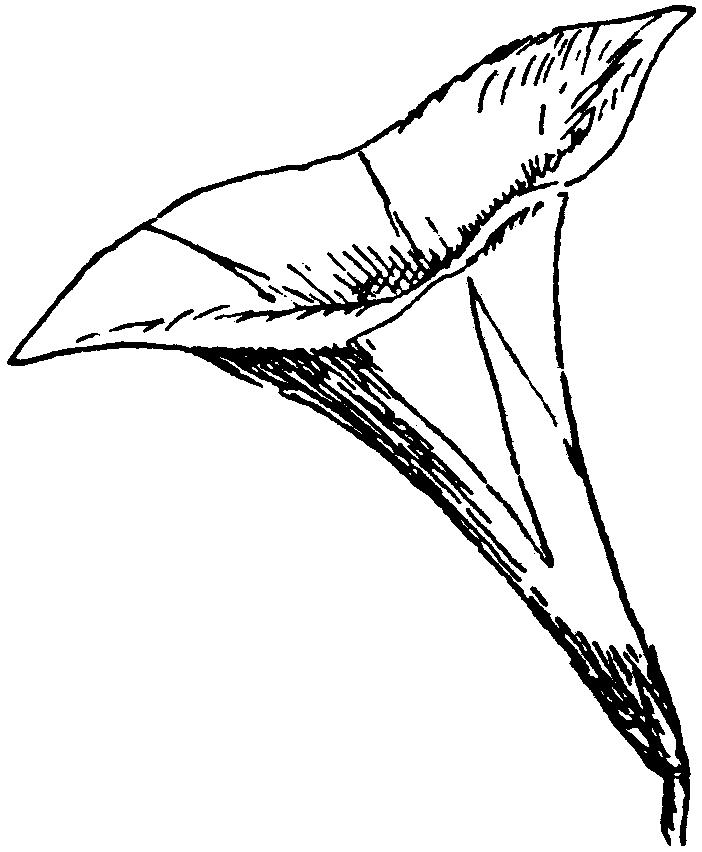

Sometimes they are all grown into one piece, like the funnel-shaped flower of the morning-glory.

THE MORNING-GLORY WITH THE PETALS GROWN TOGETHER INTO A FUNNEL

The bees can see the bright colors of the flowers a long way off. The can also smell them, for bright flowers are generally fragrant.

Flowers make a sweet juice on purpose to feed bees and other insects. We call this sweet juice nectar, and the bees take it home and make honey of it.

The flowers like to have the bees come and take the nectar. Why, do you suppose? If you have studied flowers, you will know; if you have not, I must try to tell you.

You know there is a yellow dust in some flowers. It gets on your face when you smell of them. Sometimes flower dust is brown and sometimes it is white. If you shake a golden-rod in the fall, a cloud of yellow golden-rod dust will fly out. This dust is called pollen.

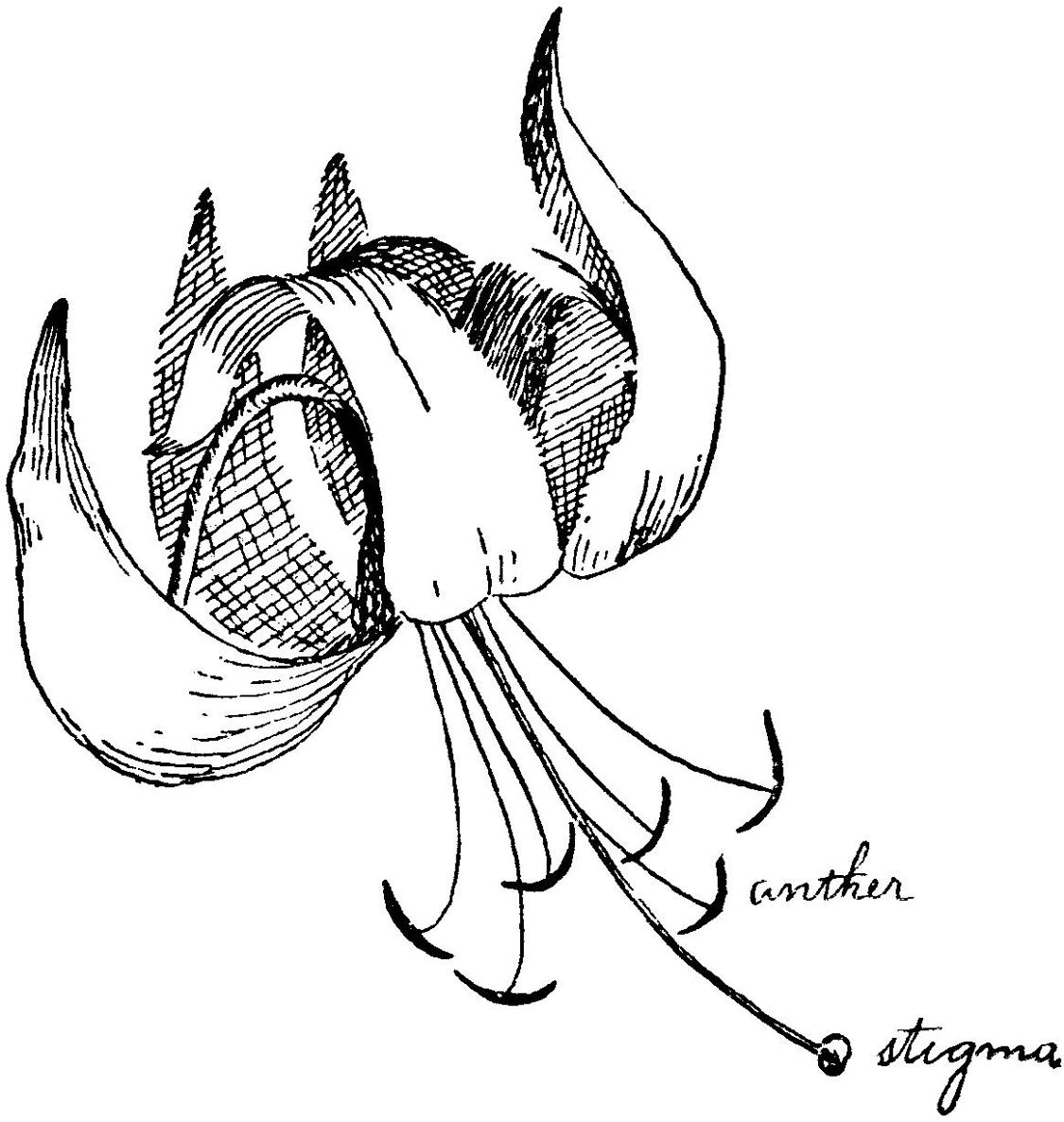

Nearly all flowers have it. It grows in little boxes called anthers; and when the anthers are ripe; they burst open and let out the pollen.

You know how the anthers in a lily look. They swing on the ends of the six long slender stems that stick out of the lily flower.

Nearly all flowers have anthers, but some do not have stems to the anthers. Sometimes the anthers grow right against the inside of the flowers, but wherever they may be they always contain pollen.

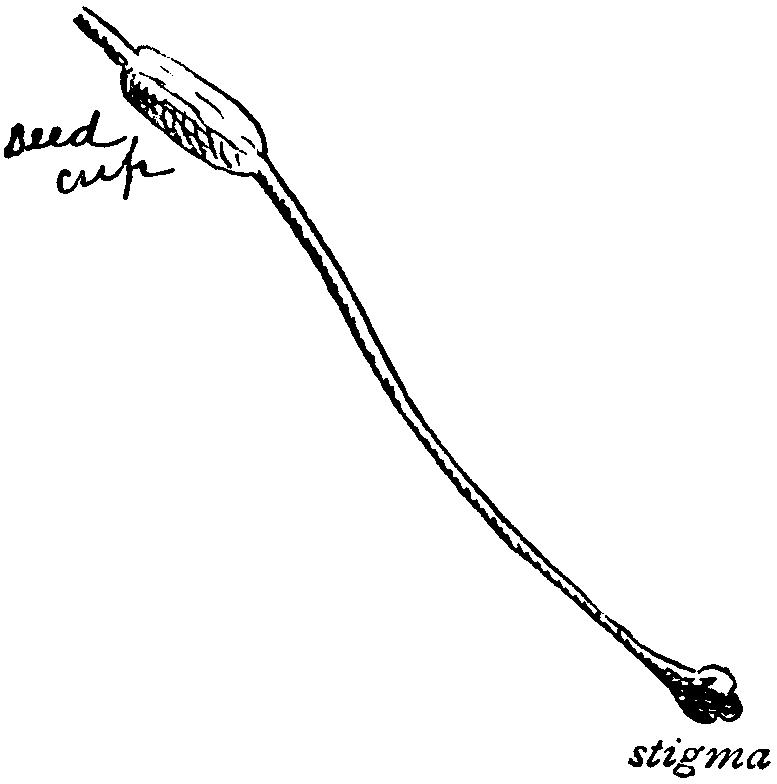

In the centre of the flower is another part that looks a little like an anther; its stem is long, and it is marked stigma in the picture. This stigma is not filled with pollen. It is just a sticky knob

When it gets ripe it gets sticky. If any pollen touches it, the pollen sticks fast. If you take away the petals and the anthers and their stems from the lily, this is what you will have left.

You see it is the stigma and its long stem, and there is another knob at the other end of the stem opposite the stigma. This other knob is hollow. It is a seed-cup and is filled with seeds. The seeds cannot grow without pollen.

If the pollen gets on the stigma, then all goes well. The sticky stigma holds it fast. It finds its way down through the long stem to the little seeds. It nourishes them, and they grow. But if the pollen does not come, the seeds die.

Flowers do not like their own pollen. One lily prefers the pollen from another lily.

It is better for the seeds. But how to get this pollen?

Why, the hairy-coated bees bring it, to be sure.

And now you see why the flower makes nectar.

It wishes to coax the bees to come. When the bees go down to the bottom of the flower after nectar, they will be sure to get their coats dusty with pollen. Then they fly to anther flower, and some of the pollen on their coats is rubbed against the stigma and stuck fast there.

The nectar is always placed so that the bees have to touch the anthers and the stigma of the flower on their way to the feast.

Many flowers have bright lines or spots leading to the nectar that the bee may lose no time in finding it. These are called nectar guides, and you can see them very plainly in the morning-glory.

Many other insects besides bees visit flowers. Butterflies and moths and flies and even some beetles are fond of nectar and pollen, and they all carry pollen about from plant to plant.

When insects carry pollen to the stigmas, we say they fertilize the flowers. Unless a flower is fertilized, it will bear no seed.

Bees eat pollen as well as honey, and while gathering it from different flowers they are sure to dust the stigmas.

Flowers can be fertilized only by pollen from other flowers of their own kind. Lilies can be fertilized only by pollen from other lilies, and roses by the pollen of other roses. Lily pollen cannot fertilize a rose, nor can any pollen fertilize any flower but one of its own particular kind. The three chief parts of a bee are the head, the thorax, and the abdomen.

The head bears the antenn, tongue, and eyes.

The thorax has attached to it the wings and legs. In the abdomen are the sting and the honey-sac.

Contents

Apis Mellifica, or the Honey-Bee

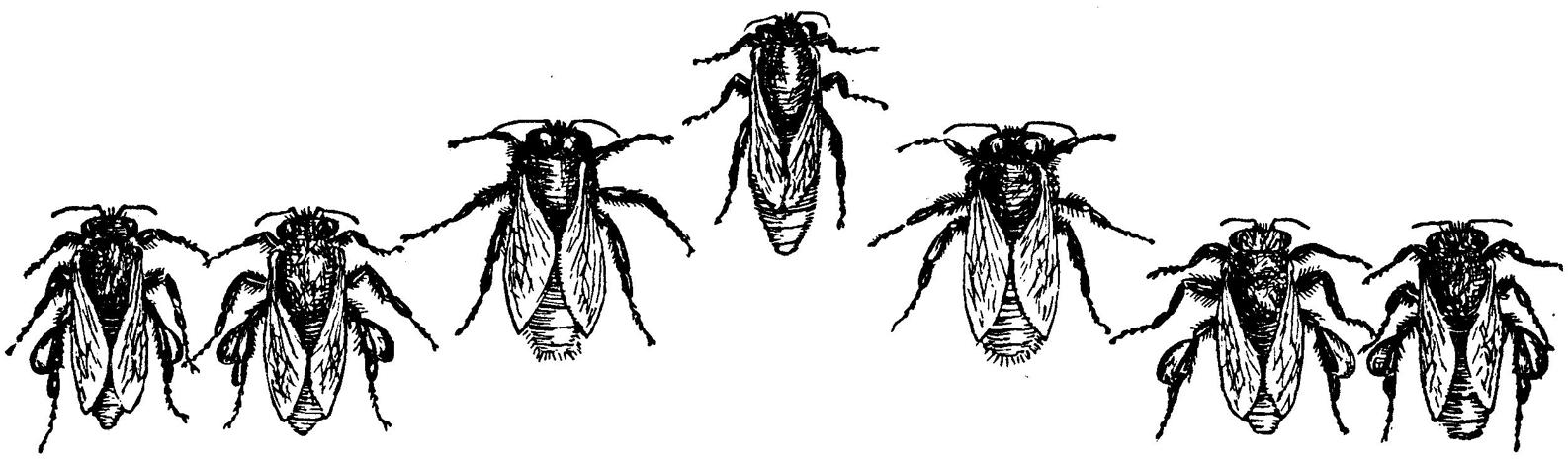

T HE honey-bees are buzzy, fuzzy little pepper-pots.

They have pretty, shining wings, but if you so much as touch one of them you will see what happens!

You cannot wonder that they do not like to have you come too near, for they are such little creatures that even a small child must seem to them a tremendous giant.

How would you like to see a great warm creature as large as a hill come lumbering up and try to put a finger the size of a church steeple upon you?

I am sure you would do anything to keep it away, and if you had a good sharp sting you would use it. So we must not blame the Bee People for stinging us.

It is the only way they have of telling us to keep away and let them alone.

They are friendly enough to their own relations, as you will agree when you learn that there are sometimes as many as sixty thousand of them living happily together in one family.