PENGUIN BOOKS

ON READING

THE GRAPES OF WRATH

SUSAN SHILLINGLAW is a professor of English at San Jose State University and scholar in residence at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California. For eighteen years she was director of the Center for Steinbeck Studies at SJSU, and she received the 20122013 SJSU Presidents Scholar Award. She is the author of Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage and A Journey into Steinbecks California, and has edited several Steinbeck volumes. For Penguin Classics, she has written introductions to The Portable Steinbeck, OfMice and Men, Cannery Row, A Russian Journal, The Winter ofOur Discontent, and America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction, which she also coedited.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published in Penguin Books 2014

Copyright 2014 by Susan Shillinglaw

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Shillinglaw, Susan, author.

On Reading the Grapes of Wrath / Susan Shillinglaw.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-14-312550-1 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-698-14609-9 (eBook)

1. Steinbeck, John, 19021968. Grapes of wrath. 2. Steinbeck, John, 19021968Influence. I. Title.

PS3537.T3234G888 2014

813'.52dc23 2013042937

Version_1

For the phalanx of Steinbeck critics who have loved The Grapes of Wrath and inspired my thinking, especially Jack Benson and Bob DeMott, mentors; Louis Owens and Warren French, in memoriam; John Seelye, beacon; and Bill Gilly, always.

CONTENTS

P REFACE

A NNIVERSARIES HELP US reconsider. When The Grapes of Wrath marked its golden year, in 1989, the television program Sunday Morning, gracefully moderated by Charles Kuralt, aired a segment on the novel. It begins with the authors son John IV reading the opening paragraph, the camera cutting between his reading, clips of the Dust Bowl, and rain falling on Steinbecks statue in front of the John Steinbeck Library in Salinas, California, the authors hometown. While the opening segment is intimate and familial, the closing scene of this program is broad and urgent. It ends with Tom Joads final speech to Ma, Henry Fondas words (from the 1940 film of Grapes) laid over clips of the homeless in New York City, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the angry student protesters in Tiananmen Square. I have replayed this many times for classes. Each time I tear up because it makes Steinbecks words so urgent and essential for a compassionate world.

Steinbeck wanted that kind of reaction, Im sure, since its only when we feel deeply about somethinghuman rights, immigration reform, gun controlthat things finally happen. Tom Joads single paragraph exit from the novel is an impassioned plea for connection with other humans and participation in an agitated world. Care about the woe of others, as Tom promises to do, and then, perhaps, something will happen.

Tom isnt a reformer. He has no answers, no solutions to any one social problem. His speech unrolls as a series of pictures, rough outlines whose details are to be filled in fifty and seventy-five and one hundred years after the books publication: Wherever theys a fight so hungry people can eat, Ill be there. Wherever theys a cop beatin up a guy, Ill be there. The reader supplies the particulars, and our history since the 1939 publication of The Grapes of Wrath has given us many scenes that are sadly appropriate: the public space of Chinas Tiananmen Square has become Egypts Tahrir or Turkeys Taksim; the fall of the Berlin Wall has become the Arab Spring. And 1989s repossessed farms have become repossessed homes a quarter century later. Reviewing the fiftieth anniversary edition of the novel, the author William Kennedy said that this book is a vivid 50-year-old parallel to the American homeless: a story of people at the bottom of the world, bereft and drifting outcasts in a hostile society. And while migrant housing has steadily improved throughout California and elsewhere, the homeless remain on the streets of cities and towns, camping in forest retreats.

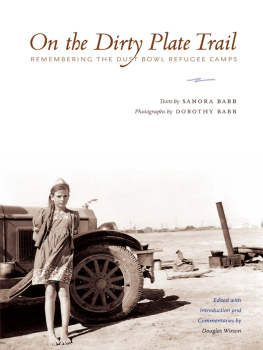

Another picture, replicated throughout history. On May 19, 2013, the New York Times ran an article on Syria by Thomas Friedman, Without Water, Revolution. The mix of contributing factors in Syrias conflict is eerily familiar: starting in 2000, big farmers were allowed to buy up land and drill for unlimited water, thus diminishing the water table; small farmers started abandoning their dry land for the towns and cities (in some towns, populations swelled from 2,000 to 400,000 people in a decade); and an extreme weather event, drought, between 2006 and 2011 accelerated the exodus. And that lethal ecological mix helped to fuel a rebellion. In effect, the Syrian picture seems not unlike the story of 1930s croppers in Dust Bowl Oklahoma at the mercy of California agribusiness, but without a sympathetic government (in Syria).

The Grapes of Wrath is a novel that wont be contained by its setting, the 1930s. Certainly its about a particular time and place and peoplethe Oklahoma migrants who made their way ever so slowly to California, imagining a new start in the state of orange groves and verdant fields. And there is urgency in the particularity of that moment. Steinbeck is at his best in helping us see clearly the diaspora of Dust Bowl migrants in the 1930s: the pork they salt and clothes they wear; the dust that covers the houses they leave and the rules that govern the camps they create along the way; and the steady, crawling movement along U.S. Highway 66. But everywhere in this book, starting with the biblical cadence of the opening chapter, Steinbeck nudges readers out of the 1930s into the timeless and the mythic. The Joads themselves would not have seen their flight from Oklahoma to California as an Exodus to a promised land. They would not have seen themselves as latter-day everymen, trudging to a world of possibility, or on an odyssey to find home. Tom Joad would not have compared himself to Joe Hill, labor organizer, or to Christ, committed to the meek. But Steinbeck did. He suggests all these parallels, and in so doing lifts dispossession and yearning for a decent life from one time to all time. The Joads become the Syrians huddling near Turkish or Lebanese borders, or Mexicans reaching hands through fences at Americas border, or the hungry, the jobless, and the exiled everywhere.

Let me suggest the power of this book by quoting from Steinbecks next, a kind of intertextual urgency that is, I think, appropriate when reading