Looking for Harper Lee

Two essays

Mark Childress

Smashwords edition. Copyright 2015 by Mark Childress.

No part of this document or the related files may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 9781476069739 (ePUB)

I wrote the essay Looking for Harper Lee, in 1993, when Miss Lee was still hiding from the public. This changed gradually over time.

The second essay, Something in the water, is adapted from remarks I made upon accepting the Harper Lee Award in 2014.

Contents

Looking for Harper Lee

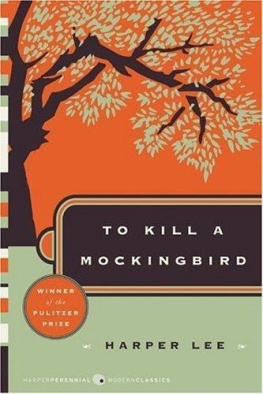

With a sad smile I close the cover of To Kill A Mockingbird, a book I hold close to my heart. Every year or so I read it again, to see if its as good as I remember, and to remind myself why I wanted to become a writer. This is the book that did it for me, the first grown-up book I ever read, the one that has stayed with me longest.

Ill never forget where I was that first time: on Miss Wanda Biggs front porch in Monroeville, Alabama, my hometown, a few doors down from the house where Nelle Harper Lee grew up. It was my particular luck to enter the world of Jean Louise Finch (better known as Scout), her brother Jem, father Atticus, the peculiar boy Dill from next door, and all the good and bad people of Maycomb, Alabama, while I reclined in a porch swing on the street where it all happened.

My family had moved away from Monroeville by that time, but we came back in the summers to visit Miss Wanda and Mister Fred and their dog Whizzy. The Biggses lived in a big old rambly house with rooms on both sides of a long dogtrot hallway, and a deep, shady porch on the front.

Over supper, I heard the grownups talking about Nelle Harper Lee, who was by far the biggest celebrity Monroeville had ever produced. Her book spent eighty weeks on bestseller lists, won the Pulitzer Prize, and went on to become a first-rate Hollywood movie, which led to the biggest event in the history of Monroeville: the day Gregory Peck came to town.

Everyone thought Miss Nelles success was wonderful, but some in town were already pondering her well-known tendency toward reclusiveness. Nothing provokes the sociable Southerner like someone who wants to be left alone, and from the time of her enormous success Harper Lee had shown absolutely no interest in acting like a celebrity. These southern people are southern people, she said in 1961, and if they know you are working at home, they think nothing of walking in for coffee.

I asked Miss Wanda if she had a copy of the book I could read. She led me gravely to the glass-fronted case in the hall and handed over her copy of J.B. Lippincotts first 1960 edition, inscribed in an open, ladylike hand: To Wanda, love, Nelle.

Tucked in the front cover was a black-and-white snapshot of Miss Wanda cheek-to-cheek with Gregory Peck at the LaSalle Hotel on Monroevilles courthouse square. She asked me to take special care with the book, as it would be worth a lot of money someday.

I stretched out on the swing, my bare feet on the chain, rocking sideways, and read the opening sentence: When he was nearly thirteen, my brother Jem got his arm badly broken at the elbow.

Some hours later, I stumbled out of the swing, the closing lines ringing in my head: He turned out the light and went into Jems room. He would be there all night, and he would be there when Jem waked up in the morning.

In those hours, I was transformed. Books had always been magical objects to me, but distant from my own experience. Authors were invisible wizards who swept me off to far places to work their magic on me. To Kill A Mockingbird was fiction, but it was real. It came from this place where I sat. It was written by a lady my parents actually knew, a lady who had signed her name in this book I held in my hands. It told a story about a childhood lived on this very street, in these houses, in these side-yards, in the schoolyard back yonder.

And not just a story -- the most wonderful story Id ever read. Certainly it seemed so to me at the time, and Im not sure that Ive changed my mind. The book moved me as no book had ever done. It made me want to learn how to make that kind of magic, to tell that kind of truth.

Thirty-seven years after its publication, the book moves me still. Many Americans consider it their favorite novel -- a certified classic, seventeen million copies in print, translated into forty languages, assigned reading in nearly every high school in our land. What no one could have predicted was that To Kill A Mockingbird would become for the South of the 1960s what Uncle Toms Cabin was to the North, a hundred years earlier: a novel to change the minds and arouse the consciences of a whole country. I believe that Harper Lees charming story was in fact a work of subversive literature, a popular book that did more to change white Southern attitudes about issues of race than any other work of art in this century.

How did the author work this miracle? She begins gracefully, easily, with that ominous glancing reference to Jems broken arm, a quick geneaology of the Finch family and a tour of Maycomb, a tired old town when I first knew it. Then were out in the yard with Scout and Jem and Dill, telling spooky stories about the house where Boo Radley lives.

Scout is the perfect narrator, a funny little girl with a tart sense of injustice, as sublimely pure and smart-mouthed an innocent as any since Huckleberry Finn. Boo Radley is the boogeyman up the street, the recluse who never leaves his creepy shabby house, the man who wants only to be left alone.

Atticus Finch, widower attorney, treats his children with courteous detachment. He is raising them with the help of Calpurnia, our cook, actually the mother figure in the household, a source of wisdom and strength. Scout gives us a lovely, affectionate picture of growing up in the vanished world of smalltown Alabama in the 1930s, where everyone seems loving and lovable, eccentric but good-hearted, poor but happy. Life feels almost painfully sweet.

Only after the author has meticulously built this fond portrait does she proceed to undermine it, revealing the rottenness at the core of all that polite gentility. Atticus takes a case that he knows will mean trouble. A black man called Tom Robinson is accused of raping and beating a white girl, Mayella Ewell. Normally this would be an open-and-shut case, but Tom is a good Negro, and Mayella comes, literally, from trash -- the Ewells live in a shack beside the town dump.

The white people of Maycomb are roused from their summertime torpor to side against Atticus, simply because he dares to defend a black man against the charges of a white girl. The facts of the case do not matter. Trapped in the elaborate system of oppression they have helped to construct, the people of Maycomb have no choice: they must side with white against black, or risk destroying the illusion that supports their way of life.

The trial of Tom Robinson strikes Maycomb like a bolt of lightning, revealing layers of hidden bigotry along with glimmers of occasional humanity. In the bravura courtroom scene at the heart of the novel, Atticus proves Toms innocence beyond doubt. In the end, though, the jury must find him guilty, because the need to preserve the whites-only system is stronger than any notion of justice.

Jem says hes got it all figured out. Theres four kinds of folks in the world. Theres the ordinary kind like us and the neighbors, theres the kind like the Cunninghams out in the woods, the kind like the Ewells down at the dump, and the Negroes.

Scout contradicts him: Naw, Jem, I think theres just one kind of folks. Folks.

Then Jem asks the unanswerable question: If theres just one kind of folks, why cant they get along with each other? If theyre all alike, why do they go out of their way to despise each other? Scout, I think...Im beginning to understand why Boo Radleys stayed shut up in the house all this time...its because he