Praise for

The Jaguar Smile

Written with a novelists eye for irony and metaphor [Rushdie] is able to make us see that the factual reality of this country already verges on the surreal.

The New York Times Book Review

To say of The Jaguar Smile that it is a work of art is to take full note of its literary allusions, its uncompromising sensitivity to death and destruction, its ready political eye for the funny and grotesque, and above all its understated and gripping eloquence.

E DWARD W. S AID

A look at intelligence struggling, with limited success, not to be entirely extinguished in the service of faith an account of the confusion any one of us might feel if we visited Nicaragua and gave it a chance to affect us, because it is an inescapably affecting land, crashing through abrupt change that escapes the easy categories of ideologues good reading.

The New York Times

The account that emerges is, as one would expect, quickened by a novelists eye. Compelling.

Time

A LSO BY S ALMAN R USHDIE

FICTION

Grimus

Midnights Children

Shame

The Satanic Verses

Haroun and the Sea of Stories

East, West

The Moors Last Sigh

The Ground Beneath Her Feet

Fury

Shalimar the Clown

NONFICTION

Imaginary Homelands

The Wizard of Oz

Step Across This Line

SCREENPLAY

Midnights Children

ANTHOLOGY

Mirrorwork (co-editor)

2008 Random House Trade Paperback Edition

Copyright 1987, 1997 by Salman Rushdie

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House Trade Paperbacks, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE T RADE P APERBACKS and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Viking, a division of Penguin Group (USA), Inc., and in London by Pan Books in 1987.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Marxist Educational Press for permission to reprint the English translations of the poems that appear on . All translations were originally published in Nicaragua in Revolution: The Poets Speak, edited by Brigit Aldaracia, Edward Baker, Ileana Rodriguez, and Marc Zimmerman (Minneapolis, MN: Marxist Educational Press, 1980). Reprinted by permission of Marxist Educational Press.

eISBN: 978-0-307-78666-1

www.atrandom.com

v3.1

For Robbie

There was a young girl of Nicragua

Who smiled as she rode on a jaguar.

They returned from the ride

With the young girl inside

And the smile on the face of the jaguar.

A NON

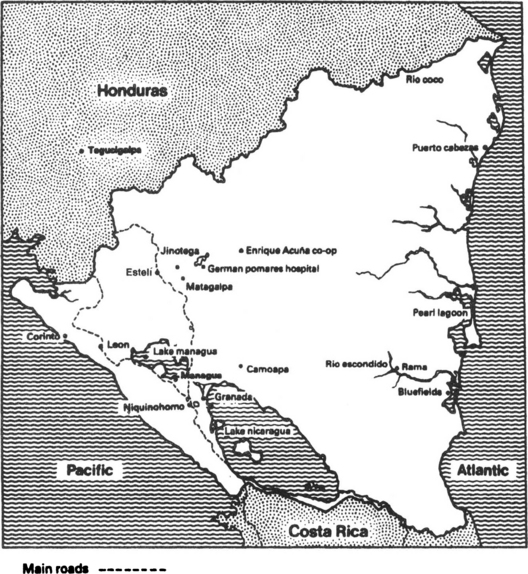

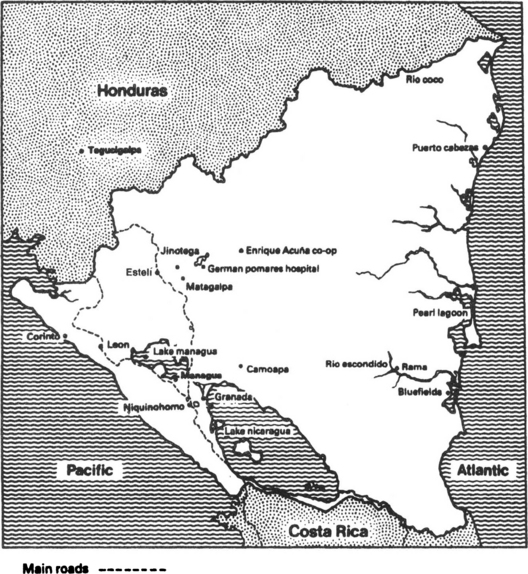

Map of Nicaragua

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE 1997 EDITION

I ts ten years since The Jaguar Smile was published. It was my first nonfiction book, and I well remember the shock of emerging, for the first time, from the (relatively) polite world of literature into the rough-and-tumble of the political arena. In the United States, then deeply involved in the low-intensity proxy war against Nicaragua, the tumbling was particularly rough. After my publication party in New York, I found myself at dinner at a wealthy uptown address, surrounded by the bien-pensant liberal lite. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., on hearing that Id written a book about Nicaragua, embarking on a debunking of the Sandinistas that focused wittily on their mode of dress and lack of good society manners. This was a warning sign. If American liberals were so casually dismissive, conservatives were bound to be worse.

And so it proved. A prominent radio interviewer, in a live broadcast, greeted me with the question: Mr Rushdie, to what extent are you a Communist stooge? The New Republic gave the book an immensely long and rude review, perhaps the most vitriolic Id ever received. It turned out to have been written by one of the most important figures in the Contra leadership. I was inexperienced enough, in those days, to be genuinely surprised that a respectable journal should so brazenly abandon the principle of critical objectivity for the sake of some controversial copy. I am more worldly now.

In the last ten years, the world has changed so dramatically that The Jaguar Smile now reads like a period piece, a fairy tale of one of the hotter moments in the Cold War. The Soviet Union and Cuba are bogeymen that have long since lost their power to scare us. And in Nicaragua, the Contra war finally took its toll. A war-weary electorate voted out the FSLN, electing, instead, the same Doa Violeta Chamorro whom I had rather caustically described in my pages. Daniel Ortega surprised, even impressed, many of his international opponents by accepting the voters verdict. But at the same time, the Sandinistas were harshly criticized for pushing through, on behalf of many of their most prominent members, a last-minute land-grab of valuable real estate. (I have always wondered who ended up owning the comfortable Managua villa in which I was housed.) It was a characteristically contradictory Sandinista moment. When in power, they had acted, simultaneously, like people committed to democracy and also like harsh censors of free expression. Now, in their fall, they had behaved, once again simultaneously, like true democrats and also like true Latin-American oligarchs.

The FSLN sign on its hill overlooking Managua was altered, after the election, to read FIN. The End. In fact, Nicaraguan politics continued to be anything but straightforward. Dissension struck Doa Violetas ragbag anti-Sandinista coalition almost as soon as it took power, and on many occasions she was obliged to rule with the assistance of the votes of the Sandinista opposition. I had been struck, during my stay in Nicaragua, by the incestuous nature of the ruling class. Sandinistas and right-wingers had all gone to the same schools and dated each other. Now, it seemed, they were dating each other again.

But the stresses within the FSLN, what Marx would have called its inherent contradictions, did eventually arise to unmake it. During my visit I had been unable to meet the Sandinistas military strongman, Daniel Ortegas brother Humberto, head of the armed forces. (The absence of any effective investigation of the hard-liners Humberto Ortega, Toms Borge is a weakness in The Jaguar Smile. It seems probable that they were kept away from a non-Marxist like myself.) The differences between the Ortega brothers, and the group headed by Sergio Ramrez, whose key role it had been to persuade the urban middle class to support the revolution, became untenable. Ramrez left the movement, and the Sandinistas were hopelessly split. At the personal level, too, there were ruptures. Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo separated. Some of the people I had liked and admired left the country. The poet Gioconda Belli, for example, now lives in the United States. Her relationship with post-Sandinista Nicaragua is troubled and sad. And now a second election has been lost. Daniel Ortega has claimed that Arnoldo Alemns victory was achieved by widespread ballot-rigging, but the independent team of electoral observers has ratified the election results. Now it really does look like the FIN.