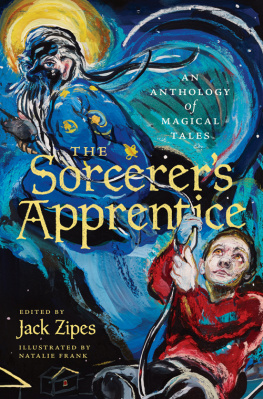

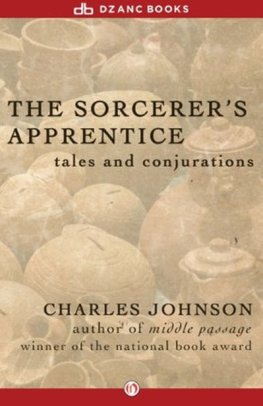

THE SORCERERS APPRENTICE

THE

Sorcerers

Apprentice

AN ANTHOLOGY of MAGICAL TALES

EDITED BY

Jack Zipes

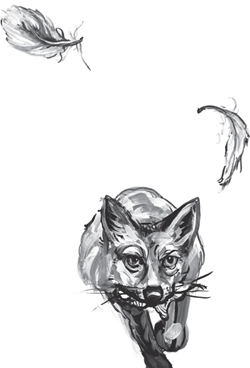

ILLUSTRATED BY NATALIE FRANK

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Illustrations 2017 by Natalie Frank

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following material:

The Do-All Ax, from Terrapins Pot of Sense by Harold Courlander. Copyright 1957, 1985 by Harold Courlander. Reprinted by permission of The Emma Courlander Trust.

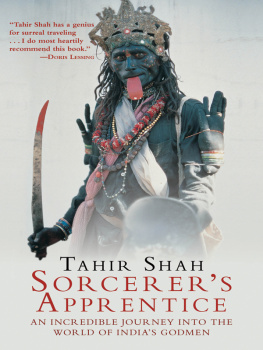

The Guru and His Disciple, from A Flowering Tree and Other Oral Tales from India, by A. K. Ramanujan, with a Preface by Stuart Blackburn and Alan Dundes (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997). Copyright 1997 by the Regents of the University of California.

The High Sheriff and His Servant, from Dog Ghosts and Other Texas Negro Folk Tales, by J. Mason Brewer (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1958), pp. 2021. Copyright 1958, renewed 1986.

Krabat, from Sorbische Volkserzhlungen, edited by Jerzy Slizinski (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1964), pp. 4550. Copyright DeGruyter.

The Magicians Apprentice by Fard al-Dn Attr, from The Ocean of the Soul: Man, the World and God in the Stories of Fard al-Dn Attr, by Hellmut Ritter, trans. John OKane with Bernd Ratke (Leiden: Brill, 2003), pp. 64041.

The Man and His Son by Corinne Saucier, from Folk Tales from Louisiana (Baton Rouge, LA: Claitors Publisher, 1962).

The Mojo, from Negro Folktales in Michigan, collected and edited by Richard M. Dorson (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1956). Copyright 1956 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

The Sorcerers Apprentice, by Richard Rostron, illustr. Frank Lieberman (New York: William Morrow, 1941).

The Two Magicians, from Tales from the French Folklore of Missouri, by Joseph Mdard Carrire (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1937), pp. 9196.

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration by Natalie Frank

Jacket and book design by Chris Ferrante

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17265-1

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Jenson with Latimer for display

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

List of Figures

Preface

Preface

I BEGAN GATHERING , translating, and writing about tales concerned with The Sorcerers Apprentice six years ago, and as I was developing this project, it gradually became clear to me why I had become infatuated with these tales: they have given me some signs of hope when it seemed that we were living in hopeless times. The more I dug into the Sorcerers Apprentice tradition, the more I discovered examples of opposition and resistance to wicked sorcerers of all kinds, who exploit magic for their own gain, and of the ways magic can enlighten readers about oppressive conditions under which they live. It is this hope that has prompted me to publish the tales in this book.

Though many of the diverse tales about sorcerers apprentices are quite old, they still speak to contemporary problems of mentorship, child abuse, and exploitation as well as the misuse of cultural and political power. For example, during the past thirty years there has been a worldwide crisis that involves the maltreatment of young people by sorcerers, the degeneration of public education, slave labor, child abandonment, poverty, and violence. The renowned scholar Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, in her book Childism, has demonstrated how adults treat young people unconsciously and consciously as possessions and slaves, seeking to mold them in their image or in the normative image of accepted success and achievement in economic, cultural, and political institutions and networks.

If childism, as Young-Bruehl argues, spread throughout the world very early in history, and if magic played a prominent role in most societies as a positive force of supernaturalism, it makes sense that all sorts of magical tales would emergeabout conflicts between children and parents, apprentices and masters, troubled families and bureaucratic and hierarchical governments, and devout and humble followers of various religions and orthodox authoritarian leadersand that these tales spread across borders and boundaries. Stories took shape from these conflicts before people knew how to write and read, preserved through oral traditions and gradually through modern technologies such as writing and printing. These tales of wish fulfillment and magical transformation articulated the human desire for social justice, autonomy, and knowledgeand still do.

No matter what the culture or society, magic represents manaa supernatural sense of knowledge and impersonal spiritual power. According to the scholars Bernd-Christian Otto and Michael Stausberg,

Magic belongs to the conceptual legacy of fifth-century Greece (BCE). Etymologically the term is apparently derived from contact with the main political enemy of that period, the Persians, and magic has ever since served as a marker of alterity, dangerous, foreign, illicit, suspicious but potentially powerful things done by others (and/or done differently). From referring to concrete objects and practices, magic eventually turned into a rather abstract category...magic has been a term with an extremely versatile and ambivalent semantics: it is the art of the devil or a path to the gods, it is of natural or supernatural origin, a testimony to human folly or the crowning achievement of scientific audacity, a sin or a virtue, harmful or beneficent, overpowering or empowering, and an act of othering or of self-assertion.

For a variety of reasons throughout the centuries, people have sought knowledge and power through magic. Tales about the desire for magic, which have evolved from words, fragments, and sentences, are not only wish-fulfillment tales but also blunt expressions of emotions that reveal what the people who tell, write, and listen to the tales lack, and what they want. Most people in the world believe in some kind of magic, whether religious or secular, and want to control magic, or mana, to escape enslavement and determine the path of their lives. According to the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, all people are stamped by what he calls our habitusthe beliefs, values, and customs that mark and shape our thoughts, values, and behavior from birth. To know ourselves and to free ourselves, Bourdieu writes, we must continually confront masters, who, if they do not learn from their slaves, will ultimately have to die in order for the slaves to gain release and freedom. Our knowledge of ourselves and the world is attained through experiencing slavery and knowing what being in slavery entails. This means that we are all involved in what the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, in

Next page

Preface

Preface