W e were leading a birding workshop group through Higbee Beach Wildlife Management Area in Cape May, New Jersey. The we consisted of me and my coleaders, Pete Bacinski and David Sibley. The group was two dozen birders of varied skill. Some were beginners, some accomplished. All had come to advance their identification skillsincluding a retired librarian who very apparently had Missouri blood flowing in her veins and who, having recognized the future author of The Sibley Guide to Birds as the youngest member of our group, took it upon herself to put David under the character-building yoke of her unbridled skepticism.

About midmorning, midweek, David looked skyward and announc ed: Theres a flock of Snow Geese. And so there was. Framed against a perfect autumn sky, an iconic wedge of migrating waterfowl.

OK, David, the librarian challenged, how do you know theyre Snow Geese?

Showing characteristic patience, David began enumerating the distinguishing characteristicsthe lines of differentiating fact and circumstance that cross over a single species.

The trick, of course, is perceiving these clues correctly and recognizing their significanceanother way of saying if you dont know what you are looking at, then you need to know what to look for and how to look for it.

Hmm. Theyre big, long-necked, short-tailed, pointy winged birds that are all white with black wing tips. Does any body see anything about these birds that is inconsistent with the identi -fi cation Snow Geese?

Well, he began, theyre big. And they have long necks, short tails, and long, pointy wings. And theyre all white with black wing tips. And theyre in a large flock, flying in a V.

He stopped. Confident that while not exhaustively complete, his enumeration of manifest traits was as sufficiently supportive as his diagnosis was unassailably true. He was wrong.

I can see all that, David, the librarian informed him. But what I want to know is how can you tell theyre Snow Geese ?

David opened his mouth to speak... but closed it over the unspoken thought.

He tried again to formulate a response, but this utterance, too, never passed his lips. I have no idea what thoughts were cascading like bumper cars along the gyri and sulci of one of the planets most analytical minds. All I can say is that, trapped in a metaphysical gridlock, David simply stood there, frozen in a paradoxical headlight.

How do you respond when someone calls into question the most fundamental tenets of your faith? That what a bird is and what it looks like are one. In this case, that birds that look and behave like Snow Geese are going to be Snow Geese.

And what do Snow Geese look like? They look like big, long-necked, short-tailed, pointy-winged birds that are all white with black wing tips and fly in a big V-shaped flock.

Just like David said.

The Basic Tenets of Bird Identification

Before proceeding, there are certain fundamental tenets of bird identification that you, as a birder, must accept on faith.

Repeat after me:

1. There is not only one bird. There are multiple speciesin fact, across the planet, about ten thousand of them.

2. Each bird species is genetically distinct from all others.

3. The distinctive traits that are unique to a species are shared by every member of that species.

4. This species-specific uniqueness manifests itself in how birds appear and behave.

5. These distinguishing characteristics can be noted in the field and, when noted correctly, can be used to distinguish one species from the rest.

There in an eggshell are the underscoring principles of field identification. And yes, they do seem obvious and unassailable hardly worth mentioning in a book. Except that not long ago, this was not the case. Field identification is a relatively new art.

Big Bang Theory

Until the end of the nineteenth century, there was no such thing as bird watching. The study of birds was a science, called ornithology, and the primary tool of ornithologists was the shotgun.

As an instrument of study, the shotgun is limited. Bring a fowling piece to your shoulder. Train it on a perched Ivory-billed Woodpecker. The bird looks just about the way it looked with the gun at your side but...

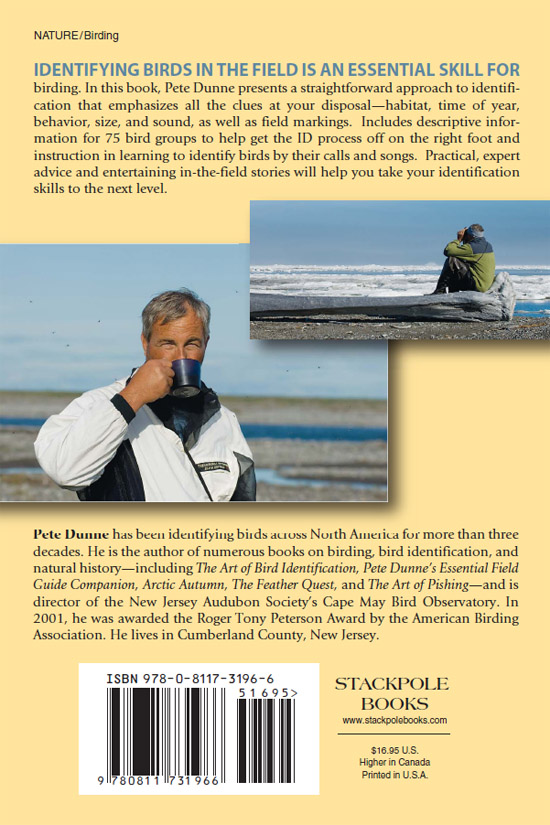

There are about ten thousand bird species apportioned across the planet. Some are widespread; others, like this male Lesser Prairie-Chicken, are more geographically restricted.

BANG!

Pull the trigger. Dust the bird with shot. Retrieve it. Youll note a transforming world of difference.

Yes, the bird is dead. Not the transformation Im speaking of. The bird is transformed by proximity. You can now see every detail, every feather, every consolidating nuance that links the Ivory-billed Woodpecker to all the other members of the scientific order Piciformes and the family Picidae and the genus Campephilus and, finally, the idiosyncratic differences that distinguish Campephilus principalis from all other woodpeckers, making it a unique species.

Most of the traits used by scientists to group, distinguish, and name species related to structure and plumage characteristics. To this day, some of the traits used in the naming of some species cannot easily be noted unless the bird is in the handtraits like the sharp shin on a Sharp-shinned Hawk or the orange crown on an Orange-crowned Warbler.

One of the advantages inherent in collecting birds was the enduring element it conferred. Encounters in the field are momentary. Now you see the bird, now you dont. But collected and rendered into a study skini.e., skinned, stuffed with cotton, preserved popsicle-style with the beak forward, wings folded, and a stick protruding from its posteriora bird presents distinguishing characteristics that can be noted, at leisure, over and over again.

When they were not being studied, these birds were stored in specimen trays and drawers, which were usually filled with other representatives of the species and closely related species. Open the drawer. Withdraw the bird. Note its distinguishing characteristics. Pin the name to the bird.

So how did the shotgun school of bird identification differ from how the practice of field ornithology, or birding, as it is conducted today? First and foremost, identifications were made in the hand, not in the field, using traits that could be noted in the hand. Bird identification today is focused on traits that can be noted at a distance, in the field, using optics. And while field identification has come a long way in the hundred years since binoculars and spotting scopes replaced the shotgun, a trio of tenets of this older approach to bird identification lingered.