HAPPILY EVER AFTER

For my daughter my dearest, loveliest Elinor Elizabeth

Steel engraving of Jane Austen, made from the sketch by her sister Cassandra as a frontispiece to A Memoir of Jane Austen by James Edward Austen-Leigh.

O n 27 January 1813 a parcel was delivered to a cottage in a small Hampshire village. The woman who opened it was middle-aged, unmarried and unknown. When she removed the parcels wrapper and took out the three books inside, she did not find her own name on the title page. Yet she still must have hugged those books with pride and delight, for the story was hers, and after seventeen years in the making it was at long last leaving the intimate family circle and was going out to make its own way in the world. The tale she had dreamed up of a young woman called Elizabeth Bennet, spirited, clever and a little prejudiced, who encounters and falls in love with a proud man called Mr Darcy, was about to face the test of readership. How would it fare? Would her story about pride and prejudice, of mistaken first impressions, sink without a trace? Or would it be read and enjoyed? And would it endure, and be read and enjoyed for generations to come?

When Jane Austen unwrapped those first copies of her Pride and Prejudice, she did not know the answers to those questions; nor could she have guessed that, with the publication of her novel, the world of literature was to be changed for ever. For like Pandoras Box, that parcel released something unforgettable upon the world; but instead of the ills and problems, the real pride and real prejudice unleashed by Pandora, Pride and Prejudice let loose a new and lasting source of joy, a heart-felt delight for the many who read it around the world.

And today, after 200 years, it has become a truth universally acknowledged that no novel is more loved. Again and again, in so many countries, it tops the polls as favourite novel of all time. It is read and studied in China; there are Jane Austen societies appreciating it around the world, even in non-English-speaking countries such as Argentina and Italy; university theses are written about it in Sweden; in India it is Bollywood-ized; in England fans take Pride and Prejudice coach tours; and Facebook has an International Pride and Prejudice Day. Brides and grooms wear Elizabeth and Darcy costumes at their weddings, cars carry I Love Darcy bumper stickers and children read the novel in comic-book form. Newspapers around the world regularly use the phrases pride and prejudice and truth universally acknowledged to grab attention in headlines, and Jane Austen is estimated to have given more pleasure to more men in bed than any other woman ever, a status she has achieved mainly through the pages of Pride and Prejudice. It has been voted the most romantic novel ever written, while Mr Darcy is considered the most romantic hero ever and millions of women swooned over Colin Firth in the role.

Why does this novel have such universal appeal? Dickenss Bleak House is a great book, and so is Charlotte Brontes Jane Eyre, yet neither novel has generated nearly the same amount of devotion, merchandise or offshoots. Happily Ever After discusses the particular brand of magic that is Pride and Prejudice. Looking at its commencement, its characters, its comedy and its charm, it celebrates 200 years of this great novel.

It examines the famous first sentence and considers why it is so brilliant; it explains the novels irony and style, its wit, its brilliant structuring, its revolutionary new techniques. It shows where Pride and Prejudice broke new ground and where it remains unsurpassed. How does Jane Austen make Elizabeth Bennet so utterly charming and why does she outclass every other heroine? And how has Jane Austen made Mr Darcy so devastatingly attractive even when he is behaving almost as badly as Mr Collins, a character every reader loves to hate? The book answers these questions, and discusses all the other characters in whom we delight and find a never-ending source of humour.

It tells the story of the birth of Pride and Prejudice and how Jane Austen had to cope with rejection and discouragement when it was first written. It describes the responses of her family, friends and earliest general public, and how the twentieth century saw the novel shoot to record fame. It describes the illustrations satisfactory and otherwise and the covers for the many editions of the book, and shows what admirers from all walks of life have had to say about Pride and Prejudice and the pleasure it has given them.

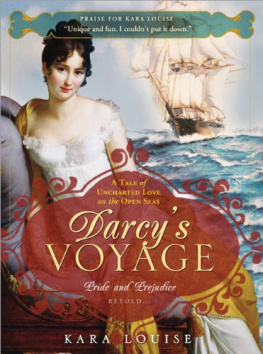

It will tell the story of how the book has travelled the world in translation and the specific difficulties it poses to anyone brave enough to try to translate it into German, Hungarian, Tamil or Hebrew and how it has morphed into strange and interesting new forms: prequels and sequels, modernizations, what-if versions, mystery novels where the crime is solved by Mr and Mrs Darcy, and even pornography. I will show how it has been used (and abused) by film directors from the first Hollywood movie of 1940 to Lost in Austen, which depicted jeans-clad Lizzy Bennet talking on her mobile on a London bus, to a planned film which depicts her slaying zombies as well as theatrical adaptations and musicals.

Manufacturers have also jumped on to the Pride and Prejudice bandwagon, responding to an apparently insatiable public appetite with Pride and Prejudice board games, Pride and Prejudice dating manuals and the like. From clubs and scholarly articles to twenty-first-century developments such as blogs and chat rooms, this book shows the many ways in which the world continues to express its enthusiasm for the novel.

All really good stories have a happy ending, and so does this one. On that historic day in 1813 Jane Austen opened her parcel and gave her Pride and Prejudice to the world. For 200 years it has lived happily ever after and, fortunately, shows every sign of continuing to do so.

The table at which First Impressions was changed into Pride and Prejudice at Chawton cottage.

THE WRITING OF PRIDE AND PREJUDICE

My stile of writing is very different from yours.

T wo days after receiving her copy of Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra. I want to tell you that I have got my own darling Child from London, she announced with delight. She had always noted with sympathy and interest the difficult pregnancies and long, painful childbirths her female relations had undergone, but the gestation of her own darling Child went on far longer than any pregnancy and was infinitely less hopeful of a positive outcome than anything her sisters-in-law endured.

According to Cassandra Austen (who recorded these dates after her sisters death and whose memory could be faulty), Jane Austen sat down at a table in Steventon parsonage, dipped her quill in the inkpot and began to write the novel that would become Pride and Prejudice some time in October 1796. She had already written the hilarious stories of her juvenilia, the tale of a ruthless adulteress called Lady Susan and an epistolary novel known then as