T he poles of the earth have wandered. The equator has apparently moved. The continents, perched on their plates, are thought to have been carried so very far and to be going in so many directions that it seems an act of almost pure hubris to assert that some landmark of our world is fixed at 73 degrees 57 minutes and 53 seconds west longitude and 40 degrees 51 minutes and 14 seconds north latitudea temporary description, at any rate, as if for a boat on the sea. Nevertheless, these coordinates will, for what is generally described as the foreseeable future, bring you with absolute precision to the west apron of the George Washington Bridge. Nine A.M. A weekday morning. The traffic is some gross demonstration in particle physics. It bursts from its confining source, aimed at Chicago, Cheyenne, Sacramento, through the high dark roadcuts of the Palisades Sill. A young woman, on foot, is being pressed up against the rockwall by the wind booms of the big semisCon Weimar Bulk Transportation, Fruehauf Long Ranger. Her face is Nordic, her eyes dark brown and Latinthe bequests of grandparents from the extremes of Europe. She wears mountain boots, blue jeans. She carries a single-jack sledgehammer. What the truckers seem to notice, though, is her youth, her long bright Norwegian hair; and they flirt by air horn, driving needles into her ears. Her name is Karen Kleinspehn. She is a geologist, a graduate student nearing her Ph.D., and there is little doubt in her mind that she and the road and the rock before her, and the big bridge and its awesome cityin fact, nearly the whole of the continental United States and Canada and Mexico to bootare in stately manner moving in the direction of the trucks. She has not come here, however, to ponder global tectonics, although goodness knows she could, the sill being, in theory, a signature of the events that created the Atlantic. In the Triassic, when New Jersey and Mauretania were of a piece, the region is said to have begun literally to pull itself apart, straining to spread out, to break into great crustal blocks. Valleys in effect competed. One of them would open deep enough to admit ocean water, and so for some years would resemble the present Red Sea. The mantle below the crustexciting and excited by these eventswould send up fillings of fluid rock, and with such pressure behind them that they could intrude between horizontal layers of, say, shale and sandstone and lift the country a thousand feet. The intrusion could spread laterally through hundreds of square miles, becoming a broad new layera sillwithin the country rock.

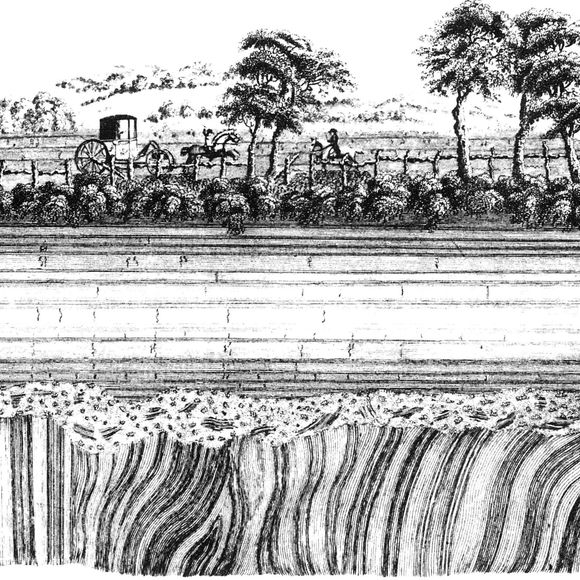

Unconformity at Jedburgh, borders, by John Clerk, 1787, courtesy Scottish Academic Press, Ltd., Edinburgh

This particular sill came into the earth about two miles below the surface, Kleinspehn remarks, and she smacks it with the sledge. An air horn blasts. The passing tires, in their numbers, sound like heavy surf. She has to shout to be heard. She pounds again. The rock is competent. The wall of the cut is sheer. She hits it again and againuntil a chunk of some poundage falls free. Its fresh surface is asparkle with crystalsfree-form, asymmetrical, improvisational plagioclase crystals, bestrewn against a field of dark pyroxene. The rock as a whole is called diabase. It is salt-and-peppery charcoal-tweed savings-bank rock. It came to be that way by cooling slowly, at depth, and forming these beautiful crystals.

It pays to put your nose on the outcrop, she says, turning the sample in her hand. With a smaller hammer, she tidies it up, like a butcher trimming a roast. With a felt-tip pen, she marks it 1. Moving along the cut, she points out xenolithsblobs of the country rock that fell into the magma and became encased there like raisins in bread. She points to flow patterns, to swirls in the diabase where solidifying segments were rolled over, to layers of coarse-grained crystals that settled, like sediments, in beds. The Palisades Sillin its chemistry and its textureis a standard example of homogeneousmagma resulting in multiple expressions of rock. It tilts westward. The sill came into a crustal block whose western extremityknown in New Jersey as the Border Faultis thirty miles away. As the blocks western end went down, it formed the Newark Basin. The high eastern end gradually eroded, shedding sediments into the basin, and the sill was ultimately revealeda process assisted by the creation and development of the Hudson, which eventually cut out the cliffside panorama of New Jersey as seen across the river from Manhattan: the broad sill, which had cracked, while cooling, into slender columns so upright and uniform that inevitably they would be likened to palisades.

In the many fractures of these big roadcuts, there is some suggestion of columns, but actually the cracks running through the cuts are too various to be explained by columnar jointing, let alone by the impudence of dynamite. The sill may have been stressed pretty severely by the tilting of the fault block, Kleinspehn says, or it may have cracked in response to the release of weight as the load above it was eroded away. Solid-earth tides could break it up, too. The sea is not all that responds to the moon. Twice a day the solid earth bobs up and down, as much as a foot. That kind of force and that kind of distance are more than enough to break hard rock. Wells will flow faster during lunar high tides.

For that matter, geologists have done their share to bust up these roadcuts. Theyve really been through here! They have fungoed so much rock off the walls they may have set them back a foot. And everywhere, in profusion along this half mile of diabase, there are small, neatly cored holes, in no way resembling the shot holes and guide holes of the roadblasters, which are larger and vertical, but small horizontal borings that would be snug to a roll of coins. They were made by geologists taking paleomagnetic samples. As the magma crystallized and turned solid, certain iron minerals within it lined themselves up like compasses, pointing toward the magnetic pole. As it happened, the direction in those years was northerly. The earths magnetic field has reversed itself a number of hundreds of times, switching from north to south, south to north, at intervals that have varied in length. Geologists have figured out just when the reversals occurred, and have thus developed a distinct arrhythmic yardstick through time. There are many other chronological frames,of course, and if from other indicators, such as fossils, one knows the age of a rock unit within several million years, a look at the mineral compasses inside it can narrow the age toward precision. Paleomagnetic insights have contributed greatly to the study of the travels of the continents, helping to show where they may have been with respect to one another. In the argot of geology, paleomagnetic specialists are sometimes called paleomagicians. Enough paleomagicians have been up and down the big roadcuts of the Palisades Sill to prepare what appears to be a Hilton for wrens and purple martins. Birds have shown no interest.

Near the end of the highways groove in the sill, there opens a broad, forgettable view of the valley of the Hackensack. The road is descending toward the river. At an even greater angle, the silltilting westwarddives into the earth. Accordingly, as Karen Kleinspehn continues to move downhill she is going upsection through the diabase toward the top of the tilting sill. The texture of the rock becomes smoother, the crystals smaller, and soon she finds the contact where the magmaat 2000 degrees Fahrenheittouched the country rock. The country rock was a shale, which had earlier been the deep muck of some Triassic lake, where the labyrinthodont amphibians lived, and paleoniscid fish. The diabase below the contact now is a smooth and uniform hard dark rock, no tweedits crystals too small to be discernible, having had so little time to grow in the chill zone. The contact is a straight, clear line. She rests her hand across it. The heat of the magma penetrated about a hundred feet into the shale, enough to cook it, to metamorphose it, to turn it into spotted slate. Sampling the slate with her sledgehammer, she has to pound with even more persistence than before. Some weird, wild minerals turn up in this stuff, she comments between swings. The metamorphic aureole of this formation is about the hardest rock in New Jersey.