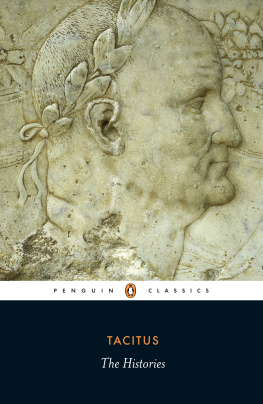

TACITUS

Annals

Translated and with an Introduction by

CYNTHIA DAMON

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

This translation first published in Penguin Classics 2012

Translation and editorial material Cynthia Damon, 2012

Cover : Detail from La Mort de Britannicus, drawing by Alexandre-Denis Abel de Pujol in the Muse des Beaux-Arts, Valenciennes, France (Photograph RMN/ Tony Querrec)

All rights reserved

The moral right of the translator has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-14-139256-1

PENGUIN  CLASSICS

CLASSICS

ANNALS

TACITUS , born in about 56 CE in southern Gaul (modern Provence) under the Emperor Nero, was probably the son of a civil servant. He was in Rome by 75, training as an orator. As Tacitus tells us in the Histories, his own political career flourished under the Flavian emperors Vespasian (6979), Titus (7981) and Domitian (8196). When that dynasty ended, Tacitus began a career as a writer. In quick succession he published the Agricola, a biography of his father-in-law, and the Germania, an ethnographical study of the peoples of Germany, both in 98. There followed (some time early in the second century) his DialogueonOrators. Today Tacitus is best known as a historian. His debut in the genre, the Histories, is a gripping narrative of the turbulent civil war that brought the Flavian dynasty to power in 69; it originally covered the whole Flavian period up to Domitians assassination in 96. His next work, the Annals, moves further back in time to cover the Julio-Claudian emperors from Tiberius (1437) to Nero (5468). Neither narrative survives complete, but both preserve Tacitus uniquely compelling historical voice and offer a chilling denunciation of the corrupting force of power in the Roman Empire. His strong moralizing ethos, together with brilliant techniques of literary artistry, combine to create a powerful and enduring portrait of imperial Rome at its best and worst. Tacitus public career reached its culmination when he won the prestigious post of proconsul of Asia (112/13). He died at some point after 115 and probably lived into the reign of Hadrian (11738), but there is no evidence for his later life or the date of his death.

CYNTHIA DAMON received her PhD from Stanford University in 1990 and taught at Harvard University and at Amherst College before moving to the University of Pennsylvania in 2007. She is the author of The Mask of the Parasite, a commentary on Tacitus Histories 1, and, with Will Batstone, Caesars Civil War. Current projects include a critical edition of Caesars Bellum civile and a study of the reception of Plinys Natural History.

Acknowledgements

Of the many translations I consulted as I worked on this project, two deserve special mention. First, the version of Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb, first published in 1888, which succeeds so well in rendering the dignity of Tacitus prose. After more than a hundred years its language has acquired an old-fashioned patina that diverts attention onto itself, and the Latin text it renders is out of date. But the words of the Church and Brodribb Tacitus have weight, as they should. And second, the 2004 version by Tony Woodman. No one can fail to admire the skill, care and precision with which he Englished Tacitus Latin, but his fellow translators, present and future, must be his greatest admirers. Some have the additional good fortune of knowing Tony himself, a peerless friend, and, if very lucky, of having heard Tony read from his translation. Giving voice, literally, to Tacitus, Tony reminds us that this text and its translations should be read aloud.

Over the years I have asked many students to read parts of this translation and to tell me what they liked and what they didnt. Somehow it was always the latter category that elicited the more detailed and lively response. Particular thanks are due to the students in my 2010 Writing History class, who read a penultimate draft and demanded changes for the final draft: Eric Banecker, Zach Dann, Hannah Keyser, Noreen Sit and Matthew Sommer. I listened. Graduate students who read drafts in tandem with Tacitus Latin performed a different, and difficult, service. I like to think that it helped them enjoy Tacitus more: Talia Hudelson, Kyle Mahoney and Jake Morton. It certainly helped me. Special thanks in this category are due to Ginna Closs, who discussed the problem of Tacitus long indirect quotations with me and pushed for a solution. Ginna also read and helped refine my early attempts at one. Carrie Mowbray stepped up to vet the notes.

This translation was the first major project I undertook after moving to Penn, and I have profited immensely from the departments collegiality and intellectual vivacity. So the volume is dedicated to my colleagues with thanks.

Further Reading

Readers who want to delve further into the world depicted by Tacitus in the Annals will find a rather different view of the same period in The Twelve Caesars, trans. Robert Graves, revised by J. B. Rives (London: Penguin, 2007), written by Tacitus younger contemporary Suetonius. A lively picture of the world in which Tacitus himself lived is available in The Letters of the Younger Pliny, trans. Betty Radice (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963), which includes letters addressed to Tacitus. Dios much later history of the period, though incomplete, helps fill in some of the major gaps in Tacitus narrative, especially the fall of Sejanus and the reign of Caligula: Dio Cassius: Roman History, VolumeVII, Books5660, trans. Earnest Cary (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library), 1924). Those who want to read more of Tacitus himself can explore his history of the Flavian period: The Histories, trans. Kenneth Wellesley, revised by Rhiannon Ash (London: Penguin, 2009) or The Histories, trans. W. H. Fyfe, revised by D. S. Levene (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). These two translations, both good, are very different in style. For works in genres other than history, readers might like to try Tacitus Agricola and the Germania, trans. Harold Mattingly, revised by J. B. Rives (London: Penguin, 2010) and

CLASSICS

CLASSICS