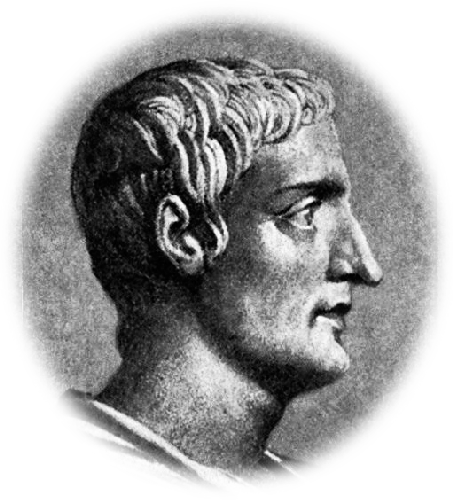

The Complete Works of

TACITUS

(AD 56AD 118 c.)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2014

Version 1

The Complete Works of

PUBLIUS CORNELIUS TACITUS

By Delphi Classics, 2014

The Translations

View of Narbonne, southern France, one of the possible birthplaces of Tacitus

THE LIFE OF AGRICOLA

Translated by John Aikin

Written circa AD 98, this biography recounts the life of Tacitus father-in-law Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the eminent Roman general, and also briefly spans the geography and ethnography of ancient Britain. The Agricola was published following the assassination of Domitian in AD 96, at a time when the turmoil of the regime change allowed a new-found freedom to publish such works.

During the reign of Domitian, Agricola, a faithful imperial general, had been the most important general involved in the conquest of a large part of Britain. The proud tone of the biography recalls the style of the laudationes funebres (funeral speeches). A quick rsum of the career of Agricola prior to his mission in Britain is followed by a narration of the conquest of the island. There is a geographical and ethnological digression, taken not only from notes and memories of Agricola, but also from Caesars De Bello Gallico . Tacitus exalts the character of his father-in-law, by demonstrating how, as governor of Roman Britain and commander of the army, he attended to matters of state with fidelity, honesty and competence, even under the government of Domitian. Critiques of this unpopular Emperor and his regime of spying and repression come to the fore at the works conclusion. Agricola remained uncorrupted; in disgrace under Domitian, dying without seeking the glory of an ostentatious martyrdom. Tacitus condemns the suicide of the Stoics as of no benefit to the state. Although Tacitus makes no clear statement as to whether the death of Agricola was from natural causes or ordered by Domitian, he does state that rumours were voiced in Rome that Agricola was poisoned on the Emperors orders.

Statue of Gnaeus Julius Agricola (AD 40-93), governor of Britannia, on the terrace of the Roman Baths, Bath, England

Domitian (AD 51-96). Bust housed in the Capitoline Museums, Rome

THE LIFE OF CNAEUS JULIUS AGRICOLA.

[This work is supposed by the commentators to have been written before the treatise on the manners of the Germans, in the third consulship of the emperor Nerva, and the second of Verginius Rufus, in the year of Rome 850, and of the Christian era 97. Brotier accedes to this opinion; but the reason which he assigns does not seem to be satisfactory. He observes that Tacitus, in the third section, mentions the emperor Nerva; but as he does not call him Divus Nerva, the deified Nerva, the learned commentator infers that Nerva was still living. This reasoning might have some weight, if we did not read, in section 44, that it was the ardent wish of Agricola that he might live to behold Trajan in the imperial seat. If Nerva was then alive, the wish to see another in his room would have been an awkward compliment to the reigning prince. It is, perhaps, for this reason that Lipsius thinks this very elegant tract was written at the same time with the Manners of the Germans, in the beginning of the emperor Trajan. The question is not very material, since conjecture alone must decide it. The piece itself is admitted to be a masterpiece in the kind. Tacitus was son-in-law to Agricola; and while filial piety breathes through his work, he never departs from the integrity of his own character. He has left an historical monument highly interesting to every Briton, who wishes to know the manners of his ancestors, and the spirit of liberty that from the earliest time distinguished the natives of Britain. Agricola, as Hume observes, was the general who finally established the dominion of the Romans in this island. He governed, it in the reigns of Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. He carried his victorious arms northward: defeated the Britons in every encounter, pierced into the forests and the mountains of Caledonia, reduced every state to subjection in the southern parts of the island, and chased before him all the men of fiercer and more intractable spirits, who deemed war and death itself less intolerable than servitude under the victors. He defeated them in a decisive action, which they fought under Galgacus; and having fixed a chain of garrisons between the friths of Clyde and Forth, he cut off the ruder and more barren parts of the island, and secured the Roman province from the incursions of the barbarous inhabitants. During these military enterprises he neglected not the arts of peace. He introduced laws and civility among the Britons; taught them to desire and raise all the conveniences of life; reconciled them to the Roman language and manners; instructed them in letters and science; and employed every expedient to render those chains, which he had forged, both easy and agreeable to them. (Humes Hist. vol. i..) In this passage Mr. Hume has given a summary of the Life of Agricola. It is extended by Tacitus in a style more open than the didactic form of the essay on the German Manners required, but still with the precision, both in sentiment and diction, peculiar to the author. In rich but subdued colors he gives a striking picture of Agricola, leaving to posterity a portion of history which it would be in vain to seek in the dry gazette style of Suetonius, or in the page of any writer of that period.]

The ancient custom of transmitting to posterity the actions and manners of famous men, has not been neglected even by the present age, incurious though it be about those belonging to it, whenever any exalted and noble degree of virtue has triumphed over that false estimation of merit, and that ill-will to it, by which small and great states are equally infested. In former times, however, as there was a greater propensity and freer scope for the performance of actions worthy of remembrance, so every person of distinguished abilities was induced through conscious satisfaction in the task alone, without regard to private favor or interest, to record examples of virtue. And many considered it rather as the honest confidence of integrity, than a culpable arrogance, to become their own biographers. Of this, Rutilius and Scaurus were instances; who were never yet censured on this account, nor was the fidelity of their narrative called in question; so much more candidly are virtues always estimated; in those periods which are the most favorable to their production. For myself, however, who have undertaken to be the historian of a person deceased, an apology seemed necessary; which I should not have made, had my course lain through times less cruel and hostile to virtue.

Next page