The Complete Works of

QUINTILIAN

(c. AD 35 c. 100)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2015

Version 1

The Complete Works of

QUINTILIAN

By Delphi Classics, 2015

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Quintilian

First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2015.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translation

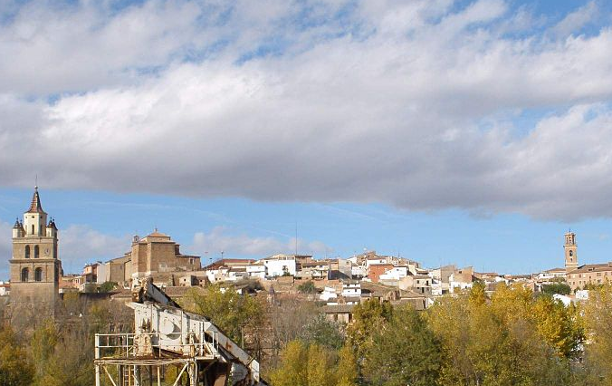

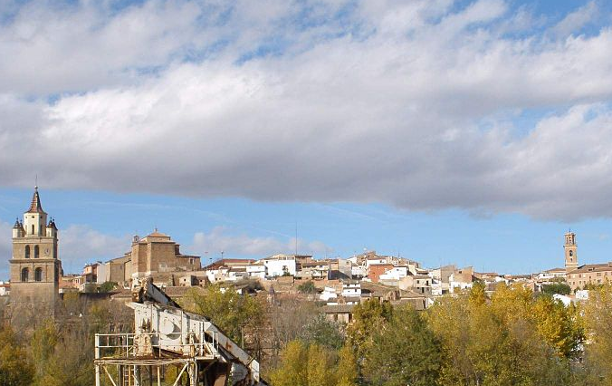

Calahorra, a town on the right bank of the Ebro, Spain Quintilians birthplace. In ancient times, Calahorra was a town known as Calagurris Fibularia. Quintilians father, a well-educated man, sent his son to Rome to study rhetoric, during the early reign of Nero.

INSTITUTES OF ORATORY

Translated by H. E. Butler

Published in c. AD 95, during the last years of the reign of Emperor Domitian, the Institutio Oratoria is a textbook composed of twelve volumes, concerning the theory and practice of rhetoric, as well as the foundational education and development of the orator himself. A native of northern Spain, Quintilian was most likely educated in Rome, having received practical training from the leading orator of the day, Domitius Afer.

Quintilian believed that the entire educational process, from infancy and beyond, was relevant to the theme of training as an orator. In Book I of the Institutio Oratoria he introduces the stages of education before a boy enters the school of rhetoric itself, to which he describes in greater detail in Book II. These first two books contain his general observations on educational principles and are notable for their good sense and insight into human nature. Books III to XI are generally concerned with the five traditional areas of rhetoric: invention, arrangement, style, memory and delivery. Quintilian also discusses the value, origin and function of rhetoric, considering in depth the different types of oratory there are, while concentrating mostly on forensic oratory (legal proceedings). During his general discussion of invention he also considers the successive, formal parts of a speech, including an animated section on the art of generating laughter. Book X includes a famous survey of Greek and Latin authors recommended to the young orator for study. Book XII concerns the authors understanding of the ideal orator in action, after his training is completed, including his character, the rules that he must follow in pleading a case, the style of his eloquence and when he should retire.

The textbook was the fruit of Quintilians wide practical experience as a teacher. His purpose, he explained, was not to invent new theories of rhetoric, but instead to judge between existing ideas, which he does with great thoroughness and discrimination, rejecting anything he considers absurd and always remaining conscious of the fact that theoretical knowledge alone is of little use without experience and good judgment. The Institutio Oratoria is further distinguished by its emphasis on morality, for Quintilians aim was to develop the students character as well as to extend their mind. His central idea was that a good orator must first and foremost be a good citizen; eloquence serves the public good and must therefore be fused with virtuous living. At the same time, he wishes to produce a thoroughly professional, competent and successful public speaker. His own experience of the law courts gave him a practical outlook that many other teachers lacked, and indeed he finds much to criticise in contemporary teaching that encourages a superficial cleverness of style (particularly the influence of the early first century writer and statesman Seneca the Younger).

Although he praises Cicero highly, Quintilian does not recommend students to slavishly imitate his style, recognising that the needs of his own day are quite different. He does, however, appear to see a bright future for oratory, oblivious to the fact that his ideal the orator-statesman of old that had influenced for good the policies of states and cities is no longer relevant with the demise of the old republican form of Roman government.

Domitian (AD 51-96) was Roman emperor from 81 to 96. Domitian was the third and last emperor of the Flavian dynasty.

CONTENTS

An eighteenth century illustration for the Institutio Oratoria, showing Quintilian teaching rhetoric

PREFACE

[1] Marcus Fabius Quintilianus to his friend Trypho, greeting

You have daily importuned me with the request that I should at length take steps to publish the book on the Education of an Orator which I dedicated to my friend Marcellus. For my own view was that it was not yet ripe for publication. As you know I have spent little more than two years on its composition, during which time moreover I have been distracted by a multitude of other affairs. These two years have been devoted not so much to actual writing as to the research demanded by a task to which practically no limits can be set and to the reading of innumerable authors. [2] Further, following the precept of Horace who in his Art of Poetry deprecates hasty publication and urges the would-be author

To withhold

His work till nine long years have passed away,

I proposed to give them time, in order that the ardour of creation might cool and that I might revise them with all the consideration of a dispassionate reader. [3] But if there is such a demand for their publication as you assert, why then let us spread our canvas to the gale and offer up a fervent prayer to heaven as we put out to sea. But remember I rely on your loyal care to see that they reach the public in as correct a form as possible.

BOOK I

[1] Having at length, after twenty years devoted to the training of the young, obtained leisure for study, I was asked by certain of my friends to write something on the art of speaking. For a long time I resisted their entreaties, since I was well aware that some of the most distinguished Greek and Roman writers had bequeathed to posterity a number of works dealing with this subject, to the composition of which they had devoted the utmost care. [2] This seemed to me to be an admirable excuse for my refusal, but served merely to increase their enthusiasm. They urged that previous writers on the subject had expressed different and at times contradictory opinions, between which it was very difficult to choose. They thought therefore that they were justified in imposing on me the task, if not of discovering original views, at least of passing definite judgment on those expressed by my predecessors. [3] I was moved to comply not so much because I felt confidence that I was equal to the task, as because I had a certain compunction about refusing. The subject proved more extensive than I had first imagined; but finally I volunteered to shoulder a task which was on a far larger scale than that which I was originally asked to undertake. I wished on the one hand to oblige my very good friends beyond their requests, and on the other to avoid the beaten track and the necessity of treading where others had gone before. [4] For almost all others who have written on the art of oratory have started with the assumption that their readers were perfect in all other branches of education and that their own task was merely to put the finishing touches to their rhetorical training; this is due to the fact that they either despised the preliminary stages of education or thought that they were not their concern, since the duties of the different branches of education are distinct one from another, or else, and this is nearer the truth, because they had no hope of making a remunerative display of their talent in dealing with subjects, which, although necessary, are far from being showy: just as in architecture it is the superstructure and not the foundations which attracts the eye. [5] I on the other hand hold that the art of oratory includes all that is essential for the training of an orator, and that it is impossible to reach the summit in any subject unless we have first passed through all the elementary stages. I shall not therefore refuse to stoop to the consideration of those minor details, neglect of which may result in there being no opportunity for more important things, and propose to mould the studies of my orator from infancy, on the assumption that his whole education has been entrusted to my charge. [6] This work I dedicate to you, Marcellus Victorius. You have been the truest of friends to me and you have shown a passionate enthusiasm for literature. But good as these reasons are, they are not the only reasons that lead me to regard you as especially worthy of such a pledge of our mutual affection. There is also the consideration that this book should prove of service in the education of your son Geta, who, young though he is, already shows clear promise of real talent. It has been my design to lead my reader from the very cradle of speech through all the stages of education which can be of any service to our budding orator till we have reached the very summit of the art. [7] I have been all the more desirous of so doing because two books on the art of rhetoric are at present circulating under my name, although never published by me or composed for such a purpose. One is a two days lecture which was taken down by the boys who were my audience. The other consists of such notes as my good pupils succeeded in taking down from a course of lectures on a somewhat more extensive scale: I appreciate their kindness, but they showed an excess of enthusiasm and a certain lack of discretion in doing my utterances the honour of publication. [8] Consequently in the present work although some passages remain the same, you will find many alterations and still more additions, while the whole theme will be treated with greater system and with as great perfection as lies within my power.

Next page