The Complete Works of

CATO

(234 BC-149 BC)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2016

Version 1

The Complete Works of

CATO THE ELDER

By Delphi Classics, 2016

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Cato the Elder

First published in the United Kingdom in 2016 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2016.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translations

Roman remains at Tusculum, an ancient city in the Alban Hills of Italy Catos birthplace

ON AGRICULTURE

Catos only extant work, De Agri Cultura is the oldest surviving book of Latin prose and is believed to have been written in c. 160 BC. Noted for his lack of form and penchant for old customs and superstitions, Cato was, nevertheless, revered by many later authors for his practical attitudes, his natural stoicism and his tight, lucid prose. The book is often characterised as a farmers notebook, written in a spontaneous fashion, appearing to be no more than a manual of husbandry intended for friends and neighbours, though its direct style and valuable depiction of rural life during the Roman Republic have won many admirers over the centuries.

The introduction to the book compares farming with other common activities of that time. Cato criticises commerce for the dangers and uncertainty that it bears and he complains of usury as, according to the Twelve Tables, the usurer is judged a worse criminal than a thief. Cato makes a strong contrast with farming, which he praises as the source of good citizens and soldiers, of both wealth and high moral values.

De Agri Cultura provides detailed information on the creation and caring of vineyards, including information on the slaves that helped maintain them. It is believed that the book inspired numerous landowners in Rome to produce wine on a large scale. Many of the new vineyards were sixty acres, as recommended by Cato, and because of their large size, even more slaves were necessary to keep the production of wine running smoothly. The book also contains a short section of religious rituals to be performed by farmers. The language of these is clearly traditional, somewhat more archaic than that of the remainder of the text.

The existing manuscripts of De Agri Cultura directly or indirectly descend from a long-lost manuscript called the Marcianus , which was once held in the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice and described by Petrus Victorinus as liber antiquissimus et fidelissimus (a book most ancient and faithful). The oldest existing manuscript is the Codex Parisinus 6842, written in Italy at some point before the end of the twelfth century. The editio princeps was printed at Venice in 1472 and Angelo Politians collation of the Marcianus against his copy of this first printing is considered an important witness for the text.

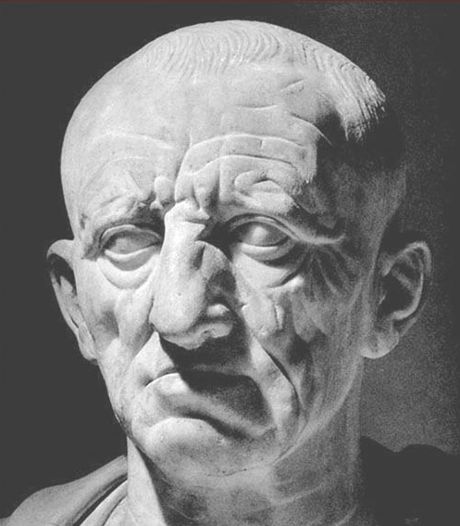

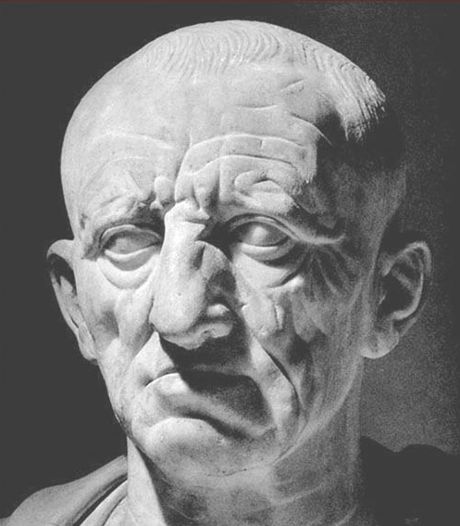

Marcus Porcius Cato (234 BC-149 BC) Cato the Elder

A Gallo-Roman harvesting machine

FAIRFAX HARRISON TRANSLATION

Translated by Fairfax Harrison

CONTENTS

Introduction: of the dignity of the farmer

The pursuits of commerce would be as admirable as they are profitable if they were not subject to so great risks: and so, likewise, of banking, if it was always honestly conducted. For our ancestors considered, and so ordained in their laws, that, while the thief should be cast in double damages, the usurer should make four-fold restitution. From this we may judge how much less desirable a citizen they esteemed the banker than the thief. When they sought to commend an honest man, they termed him good husbandman, good farmer. This they rated the superlative of praise. Personally, I think highly of a man actively and diligently engaged in commerce, who seeks thereby to make his fortune, yet, as I have said, his career is full of risks and pitfalls. But it is from the tillers of the soil that spring the best citizens, the stanchest soldiers; and theirs are the enduring rewards which are most grateful and least envied. Such as devote themselves to that pursuit are least of all men given to evil counsels.

And now, to get to my subject, these observations will serve as preface to what I have promised to discuss.

Of buying a farm

(I) When you have decided to purchase a farm, be careful not to buy rashly; do not spare your visits and be not content with a single tour of inspection. The more you go, the more will the place please you, if it be worth your attention. Give heed to the appearance of the neighbourhood, a flourishing country should show its prosperity. When you go in, look about, so that, when needs be, you can find your way out.

Take care that you choose a good climate, not subject to destructive storms, and a soil that is naturally strong. If possible, your farm should be at the foot of a mountain, looking to the South, in a healthy situation, where labour and cattle can be had, well watered, near a good sized town, and either on the sea or a navigable river, or else on a good and much frequented road. Choose a place which has not often changed ownership, one which is sold unwillingly, that has buildings in good repair.

Beware that you do not rashly contemn the experience of others. It is better to buy from a man who has farmed successfully and built well.

When you inspect the farm, look to see how many wine presses and storage vats there are; where there are none of these you can judge what the harvest is. On the other hand, it is not the number of farming implements, but what is done with them, that counts. Where you find few tools, it is not an expensive farm to operate. Know that with a farm, as with a man, however productive it may be, if it has the spending habit, not much will be left over.

Of the duties of the owner.

(II) When you have arrived at your country house and have saluted your household, you should make the rounds of the farm the same day, if possible; if not, then certainly the next day. When you have observed how the field work has progressed, what things have been done, and what remains undone, you should summon your overseer the next day, and should call for a report of what work has been done in good season and why it has not been possible to complete the rest, and what wine and corn and other crops have been gathered. When you are advised on these points you should make your own calculation of the time necessary for the work, if there does not appear to you to have been enough accomplished. The overseer will report that he himself has worked diligently, but that some slaves have been sick and others truant, the weather has been bad, and that it has been necessary to work the public roads. When he has given these and many other excuses, you should recall to his attention the program of work which you had laid out for him on your last visit and compare it with the results attained. If the weather has been bad, count how many stormy days there have been, and rehearse what work could have been done despite the rain, such as washing and pitching the wine vats, cleaning out the barns, sorting the grain, hauling out and composting the manure, cleaning seed, mending the old gear, and making new, mending the smocks and hoods furnished for the hands. On feast days the old ditches should be mended, the public roads worked, briers cut down, the garden dug, the meadow cleaned, the hedges trimmed and the clippings collected and burned, the fish pond cleaned out. On such days, furthermore, the slaves rations should be cut down as compared with what is allowed when they are working in the fields in fine weather.

Next page