THE HOLY ROMANEMPIRE

Power Politicsand the Papacy

Part of the In Brief Series: Books for Busy People

by AnneDavison

Smashwords Edition

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoymentonly. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people.If you would like to share this book with another person, pleasepurchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you're readingthis book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased your useonly, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your owncopy.

Thank you forrespecting the hard work of this author

Copyright2013Anne Davison

Cover designedby Karen Turner

TABLE OFCONTENTS

PREFACE

This is the thirdbook in the In Brief Series: Books for Busy People, theothers being From the Medes to the Mullahs; a History ofIran and Paul of Tarsus; a First Century Radical. Aswith the previous books, the content of this book began as a seriesof lectures. They are aimed at the general reader who wants tounderstand a particular historical topic but doesnt have the timeor inclination to read a heavy academic tome.

This book tracesthe history of the Holy Roman Empire, which lasted for over athousand years, from the reign of Charlemagne in AD 800 until AD1806 when it was dissolved following defeat by Napoleon. It is anEmpire that had no fixed boundaries and until the 16thcentury, when the Habsburgs settled in Vienna, it had no permanentimperial city. At different periods its territories stretched fromthe North Sea to the Balkans and for a time in the 16thcentury included the South Americas.

The first chaptercovers the rise of the Carolingian Empire in the 9thcentury and then its subsequent division into regions that roughlyequate to modern France and Germany. Chapter Two looks at theperiod of the Ottonian dynasty, a time when many of the structuresof the Imperial Church were put in place. The third chapter coversthe Salian dynasty and conflict with the Papacy over the issue ofLay Investiture.

Chapter Fourcovers the role of the Prince Electors and the process for theelection of the Emperor. The last two chapters are devoted to theHabsburgs, a dynasty that lasted from the 12th centuryuntil modern times and includes the dissolution of the Holy RomanEmpire, the foundation of the Austrian Empire and finally the fallof the Austria-Hungarian Empire after World War I.

INTRODUCTION

Francois-Marie Arouet, betterknown as Voltaire, famously said that the Holy Roman Empire wasneither Holy, nor Roman nor an Empire. Taken at face value this isprobably right. If we dig a little deeper, however, we may discoverhow and why, this entity came to be so named.

The foundation ofthe Holy Roman Empire is traditionally dated from the coronation ofOtto the Great in AD 962. However, the reign of Charles I,otherwise known as the Great or Charlemagne, who was crownedEmperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day AD 800, isusually considered to be the first Emperor of the Empire.

The coronation ofCharles was a key event in European history because it marked therevival of empire in Western Europe following the fall of theWestern Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. Charles the Great wasseen as the direct successor to Caesar Augustus and the CarolingianEmpire successor to the Ancient Roman Empire. As such, Charles, andeach successive Emperor, expected to rule with the same power andauthority as had the Emperors of ancient Rome. This relationshipwith ancient Rome was central to the self-understanding of allEmperors from Charlemagne to Francis II in the 19thcentury and it also affected the on-going relationship between theEmperor and the Pope.

When Charles I wascrowned in AD 800, the Pope anointed him as both Defender andPropagator of the Christian Faith. Crucially he was being crownedEmperor of a Christian Empire, otherwise known as Christendom.Following the European Reformation in the 16th century, all laterEmperors, down to Francis II, who capitulated to Napoleon in AD1806, viewed themselves as Defenders of the Roman Catholic Churchand the Papacy.

The Holy RomanEmpire is difficult to define; it was not an empire in theterritorial sense, but was more a confederation of kingdoms andprincipalities of all sizes; from a single castle with its estates,to a vast kingdom. It lasted almost a thousand years from AD 962until AD 1806 but had no capital city or clear boundaries. Itsinfluence spread across most of Europe and for a short time underCharles V in the 16th century parts of South America also cameunder its sovereignty.

In theory theemperors were elected, but very often the title was passed on to ason thereby establishing dynasties, for example the House ofHohenstaufen between the 11th and 13thcenturies and the later Habsburgs who ruled almost continuouslyfrom the middle of the 15th century onwards.

The early emperorschose their own capital: for Charles the Great it was Aachen, Ottothe Great it was Magdeburg, Otto III it was Bamberg. The laterHabsburgs settled in Vienna.

For much of itshistory the power lay not with the Emperor but with the greatnobles and magnates of central Europe who made up the ElectoralCollege. It was an Empire riddled with complex politics and therelationship between the Emperor and the Papacy was extremelyvolatile, ranging from an intense suspicion to open hostility.

CHAPTERONE

TheCarolingians

Fall of theAncient Roman Empire

When the RomanEmperor Constantine the Great became a Christian in AD 313 hepromulgated an edict, known as the Edict of Milan, which gaveChristians freedom of worship in the Roman Empire for the firsttime. In AD 380, under Emperor Theodosius, the Edict ofThessalonica was issued ordering all subjects of the Roman Empireto profess the Christian faith, so making Christianity the statereligion of the Empire. As Emperor, Constantine assumedresponsibility for the spiritual wellbeing of all his subjects,while matters of doctrine were to be the responsibility of thebishops. However, it was to be the task of the Emperor to ensurethat heresy was rooted out and that the Church remained united.

From the verybeginning the relationship between Emperor and Church waspotentially open to conflict. From the time of Theodosius in the4th century there have been numerous cases where theEmperor and Patriarch in the East, or Emperor and Pope in the West,have clashed over questions of authority.

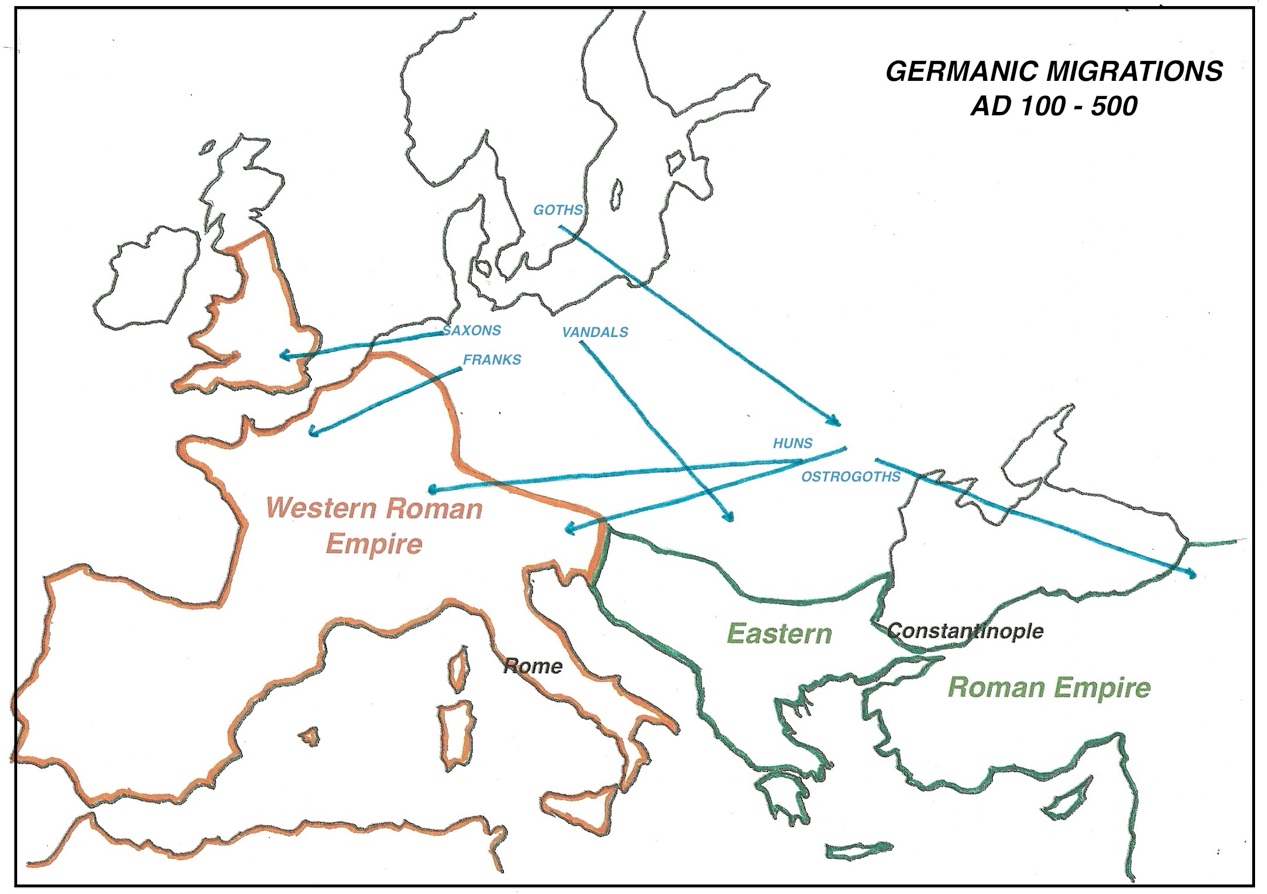

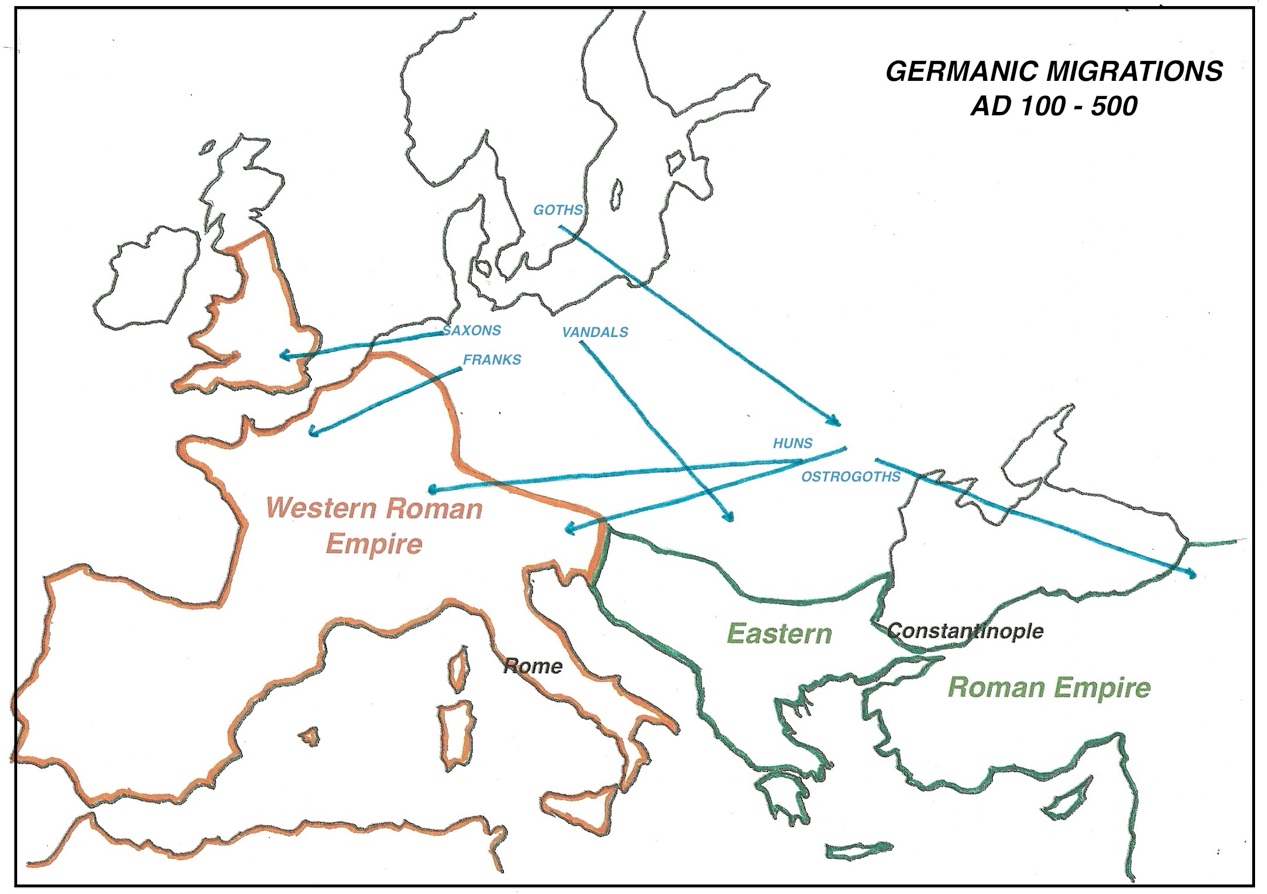

By the beginningof the 5th century the stability of the Empire was notthreatened by religious tension from within, but by an outsidethreat from the North. Ever since the 2nd century therehad been a gradual movement of tribal peoples across the Rhine andDanube, rivers that marked the Northern boundary of the Empire.Historically these migrations have been referred to as theBarbarian Invasions but today they are more correctly termed theGermanic Migrations, which reflects the fact that these people wereseeking a better life, perhaps due to climatic change or fleeingoppression from invading tribes, rather than crossing the Rhine orDanube as aggressive invaders.

The tribes camefrom the Baltic region and Central and Northeast Asia. Saxons andFranks migrated from North-Western Europe into Britain and France;Goths and Vandals migrated into Central Europe and Huns migratedfrom the North-East into Central Europe. Another group, theVisigoths, migrated as far South as Spain where they established asophisticated Christian kingdom.