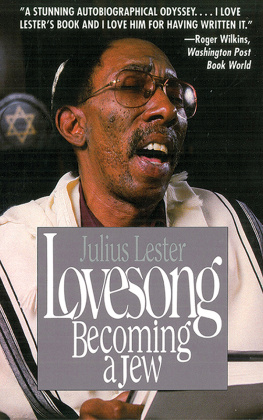

L ovesong

Also by Julius Lester

Look Out, Whiteyi Black Power's Gori Get Your Mama!

To Be a Slave

Revolutionary Notes

Black Folktales

Search for the New Land

The Seventh Son: The Thought and Writings of W.E.B. Du Bois

Long Journey Home: Stories from Black History

Two Love Stories

The Knee-High Man

Who I Am (with David Gahr)

All Is Well

This Strange New Feeling

Do Lord Remember Me

The Tales of Uncle Remus: The Adventures of Brer Rabbit

More Tales of Uncle Remus: Further Adventures of Brer Rabbit

Further Tales of Uncle Remus

The Last Tales of Uncle Remus

How Many Spots Does a Leopard Have?

Falling Pieces of the Broken Sky

And All Our Wounds Forgiven

John Henry

L ovesong

Becoming a Jew

JULIUS LESTER

ARCADE PUBLISHING NEW YORK

Copyright 1988, 2013 by Julius Lester

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or arcade@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Grateful acknowledgment is given to the following for permission to reprint:

From The Sign of Jonas by Thomas Merton, copyright 1953 by The Abbery of Our Lady of Gethsemani; renewed 1981 by The Trustees of the Merton Legacy Trust. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. From Contemplation in a World of Action by Thomas Merton, reprinted by courtesy of Doubleday and Company, Ind. From God, Sex and Kaballah by Allen S. Mailer, reprinted by courtesy of the author. Article in the New York Post by Lee Dembart, courtsey of the New York Post. Article from Katallagete is reprinted with permission. The Uses of Suffering first appeared in The Village Voice and is reprinted with permission.

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 987654321

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-802-2

Printed in the United States of America

To My Son

MALCOLM

"All my bones shall proclaim,

'O Lord, who is like unto Thee?"'

Shabbat and Festivals Morning Service

L ovesong

December 1982

In the winter of 1974, while I was on retreat at the Trappist monastery in Spencer, Massachusetts, one of the monks told me, When you know the name by which God knows you, you will know who you are.

I searched for that name with the passion of one seeking the Eternal Beloved. I called myself Father, Writer, Teacher, but God did not answer.

Now I know the name by which God calls me. I am Yaakov Daniel ben Avraham vSarah.

I have become who I am. I am who I always was. I am no longer deceived by the black face which stares at me from the mirror.

I am a Jew.

Part I

1

It is summer, any summer in the 1940s. I am with Momma and for two to four weeks we will be here, staying with her mother outside Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

Grandmomma lives with her brother, my great-uncle Rudolph, in a frame house whose unpainted boards have absorbed sun and rain, frost and dew until they are as gray as restless sleep and as weary as the sleeper who awakens to a day for which he has no love.

Grandmommas house stands alone, removed from its neighbors and back from the main road like the monarch of an impoverished kingdom. To the east is a large field, the orchard, Momma calls it still, because when she was a girl (and I cant imagine that), rows and rows of peach, apple and cherry trees flowered where now an infinite variety of weeds flourishes like immorality. On the other side of the orchard, beside the railroad tracks, is another house, smaller than Grandmommas, and even more weary. Grandmommas sister, my great-aunt Rena, lives there with her husband, Fate McGowan.

Behind Grandmommas house is the chicken yard, henhouse and outhouse. Beyond these are deep woods, somewhere in the midst of which is the family cemetery. In all, there are forty acres of fields and woods enclosed by a sturdy wire fence, whose gate no one ever enters and we seldom go out.

Beyond the fence, on the west, is a dirt road leading to and from the main one on the north. It is wide enough for a mule wagon as far as Grandmommas gate; then it narrows to a dusty footpath and winds into the innards of Pine Bluffs black community. (We were colored in those days when Hope was the name some dreamer bestowed on a daughter, when change was what the white man at the store might give you when you bought something, and progress was merely another incomprehensible word on a spelling test.)

I sit on the porch each day and watch children go back and forth to the little store on the main road. I am a child yearning to be with children, but these wear dirty and torn clothes. How am I supposed to play with someone whom dust coats like roach powder? They look furtively at me sitting on the porch in my clean and well- pressed clothes, socks and shoes(!). (Only now, looking back, do I realize that in the fifteen summers at Grandmommas, no child ever came to the gate to ask me who I was, where I was from and did I want to play. I realize only now, too, that I never went to the gate so that they could ask.)

I accept such separateness as unquestioningly as I do the air my body breathes. There is something different about usGrandmomma, Uncle Rudolph, Momma and me. In the evenings we sit on the porch and watch as trucks, filled with fieldhands who work the white mans cotton, stop on the main road in front of the store. With much laughter and loud talking, they jump or climb off and meander down the side road that leads past Grandmommas to their houses scattered over the fields behind like neglected thoughts. Their loud voices soften as they near Grandmommas. You niggers hush! Dont you see Miz Smith setting on the porch? (That was Grandmommas name when she wasnt Grandmomma.) A quietness as stifling as the heat falls upon them, fifteen, twenty, men, women and children, hoes at forty-five-degree angles across their shoulders, fraying straw hats or red handkerchiefs on their heads, and as they pass the gate, that gate they never enter and through which we seldom go out, someone calls out loudly, How yall this evening? We call back, Fine, and you? Tolable, thank you. Only after the last one passes do their voices rise again like birds from tall grasses.

We are different. Daddy is a Methodist minister and I was robed in a mantle of holiness even before the first diaper was pinned on my nakedness. I cannot do what other kids doplay marbles for keeps, go to the movies on Sundays, listen to popular music on the radio, play cards. Momma cannot wear makeup or pants. Only sinful women do that. We represent Daddy and he represents God.