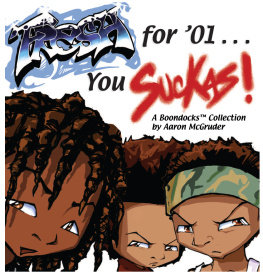

The Boondocks is distributed internationally by Universal Press Syndicate.

The Boondocks copyright 2000 by Aaron McGruder. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews.

Andrews McMeel Publishing, LLC

an Andrews McMeel Universal company

1130 Walnut Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106

www.andrewsmcmeel.com

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00-103479

The Boondocks may be viewed on the Internet at:

www.boondocks.net

ATTENTION: SCHOOLS AND BUSINESSES

Andrews McMeel books are available at quantity discounts with bulk purchase for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail the Andrews McMeel Publishing Special Sales Department:

This book is dedicated to my parents, Elaine and Bill McGruder, the first and still the best people in my life.

To my beautiful grandparents, Robert and Thelma Carrier.

To Robert Hord, Rhome Anderson, and Reginald Hudlin... my friends.

To the life and memory of Charles Schulz (Ill never get to call you Sparky), and to Garry Trudeau, Berke Breathed, and Bill Watterson, for obvious reasons.

To Jeanne McCarty, Dr. Melinda Chateauvert, Dr. Ollie Johnson, and the Afro-American Studies program at the University of Maryland for actually teaching me something in school and then helping me get the hell out.

To the NABJ, Lonnae ONeal Parker, Joann Lyons Wooten, Garry Howard, Chrisette Suter, Johnnie Cochran, Tavis Smiley, and the Black media who helped spread the word.

To W. E. B. DuBois, Malcolm X, Bob Marley, Dr. Mary Frances Berry, Lawrence Guyot, and all freedom fighters of yesterday, today, and especially tomorrow.

To Bob Johnson and Ward Connerlygreat villains make great heroes.

To Stephen Barnes, every Black persons lawyer.

To John McMeel, Kathy Andrews, Lee Salem, Bob Duffy, John Vivona, and all those other folks at the syndicate for their hard work and faith... and especially to Greg Melvin, Robert Hightower, and Pam Carr.

To Basheera James, Sharifa Foum, and Tony Millerjust for being wonderful people.

To the World-Famous Soul Controller Massive (DJ Book, DJ Stylus, Bushhead Ed, and DJ Mr. Elite).

To the hip-hop artists who used to teach Black people to love themselves... and the few who still do.

To the fans at Boondocks.net and okayplayer.com.

To Stress, for helping me get my life back.

To my adopted godmother and the reason youre reading this book, Harriet Choice.

And to the person I love most in the whole world... my brother, Dedric.

Foreword

Race is the most fertile yet untapped realm for the creation of powerful storytelling.

Put another way, conflict is drama. Race is where the conflict that is dramas bubblin crude can be found in widest abundance, and down to almost limitless depths.

But instead of mining the racial strata for the new, vital stories that racism presently withholds, or even digging for old, untold ones, todays popular storytellers are often more likely to feed their audiences gentle fictions of interracial collegiality; Black people and white people collaborating indifferently across racial lines, as though under the terms of an unearned truce.

Watch any number of TV shows or movies to view this trend in action: See the white girl with the mothering, Black roommate, or the Black guy whose best friend is the hip, smart-ass white guy. Hip-hop, certainly, seems to be in the throes of this tendency, given the increased number and prominence of both white rappers and fans, but, perhaps even more, given the current and increasing number of white, so-called rap-rockers.

Many, considering the tragedies from which Black people have risenbut perhaps, even more, the barbarism from which white people have comesee this lack of racial differentiation as progress. Why do we have to keep bringing up the past? they ask.

Because those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it, answers philosopher George Santayana. The truth of races fundamental divisiveness and apparent permanence, no matter how harsh or unexpected, always makes better retelling than a jaw full of fantasy or wishful thinking about it.

Aaron McGruder, meanwhile, also thinks frankness in racial matters makes better punch lines. Of course, hes right. His commitment to candor in comedy is what makes The Boondocks the most potent new entry in the comic strip medium since the early 1970s, when Garry Trudeau first started smacking sacred cows in Doonesbury . Its what makes The Boondocks the most successful debut strip in the history of Universal Press Syndicate, which launched it in 160 newspapers on April 19, 1999, then grew that list to over 200 dailies by that years end. (The syndicate had expected it to debut in, perhaps, 30 to 50 papers.)

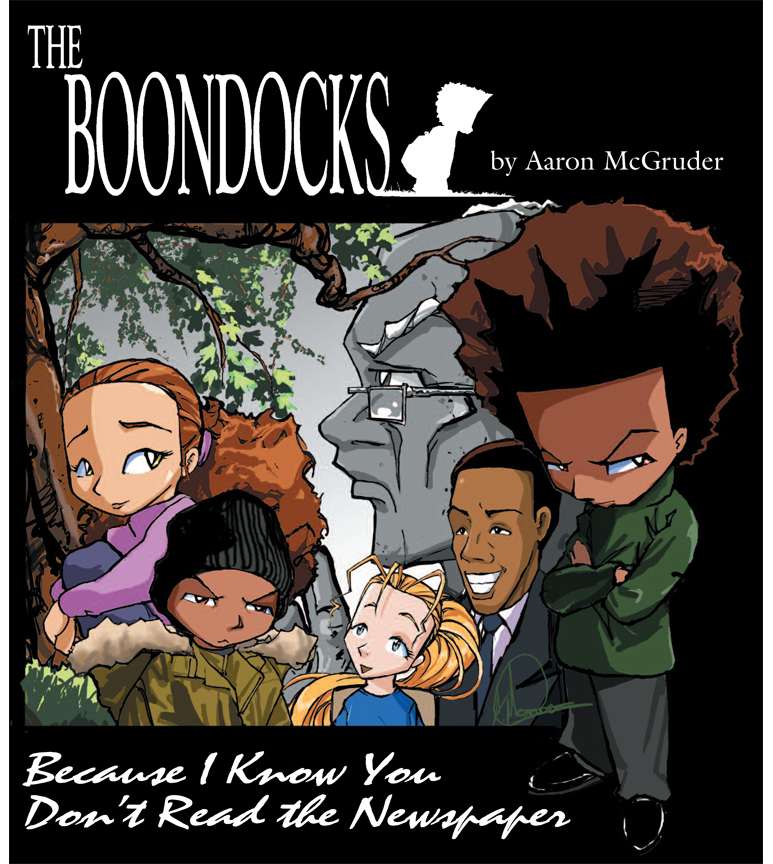

Its also why, once having read The Boondocks , few are indifferent about itif the small, but noteworthy number of newspapers that have canceled the strip is any indication. While the comics premise is deftly straightforward, it is certainly not innocuous. As social construct, the tale of Huey and Riley Freemantwo prepubescent African-American males who leave Chicagos South side to live with their grandfather in the blindingly white suburb of Woodcresttakes place right at the nexus of white American racial anxiety; that moment where their neighborhoods start changing : changing being code for Black people are moving in.

What marks McGruders sensibility as wonderfully perverse, though, is the way he, having set up that initial set of conditions, begins to drop in the details that will make it weirdly unravel, like a cartoon strip version of The Sims . In The Boondocks , the Freemans are just under twelve parsecs away from those cuddly, wide-eyed, Negro comic strip innocents weve grown to know and hate. Huey Freeman is a pint-sized, foot-high-Afro-wearing, razor-tongued Black revolutionary, and Riley is a half-pint-sized, platinum-coveting, foul-mouthed roughneck. Like Cain and Abel, they signify two long-standing, mutually opposed, vigorous traditions in the so-called Black community, clasped in uneasy, brotherly embrace.

Their foils? Their Southern, traditionalist grandfather, completing the symbolic triad of Black American modalities represented in the Freeman home: radical, integrationist, thug; a biracial girl, Jazmine DuBois; her Black father, Tom, and his white wife, Sarah, both lawyers; and Cindy, a white girl so clueless she has no idea why her request to touch Hueys different... cool hair (p. 73) returns the promise of a pummeling.

With the addition of a few more minor characters, McGruder then rudely impales everything from Jar-Jar Binks, Star Wars fandom, telemarketers, and the NAACP to Puff Daddy, Black Entertainment Television, and Santa Claus. Certainly the only comic strip in history to have a character deem the U.S. was built on stolen land, advocate the formation of a local Klanwatch, and brutally dis Ward Connerly, The Boondocks avoids the boorishness to which others might sink by virtue of McGruders light saber-sharp intelligence, the drollness of his drawing style, and the consistency of his characters and their universe.

And, oh yeah: Its mad funny. My conversion came early in the strips history, the moment Huey, meeting Jazmine for the first time, offhandedly called her Mariah, as in Carey. I think I screamed till my sides ached.