HOW CARROTS WON THE TROJAN WAR

HOW CARROTS WON

THE TROJAN WAR

Curious (but True) Stories of

Common Vegetables

Rebecca Rupp

The mission of Storey Publishing is to serve our customers by

publishing practical information that encourages

personal independence in harmony with the environment.

Edited by Deborah Burns

Art direction and book design by Mary Winkelman Velgos

Text production by Jennifer Jepson Smith

Illustrations by Gilbert Ford

Indexed by Samantha Miller

2011 by Rebecca Rupp

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages or reproduce illustrations in a review with appropriate credits; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other without written permission from the publisher.

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or Storey Publishing. The author and publisher disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information.

Storey books are available for special premium and promotional uses and for customized editions. For further information, please call 1-800-793-9396.

Storey Publishing

210 MASS MoCA Way

North Adams, MA 01247

www.storey.com

Printed in the United States by Versa Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rupp, Rebecca.

How carrots won the Trojan War / by Rebecca Rupp.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-60342-968-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. VegetablesHistory. 2. Vegetable gardeningHistory.

I. Title.

SB320.5.R87 2011

641.35dc23

2011020049

For Randy,

who runs the rototiller

The greatest service which can be rendered to any country is to add a useful plant to its culture.

THOMAS JEFFERSON

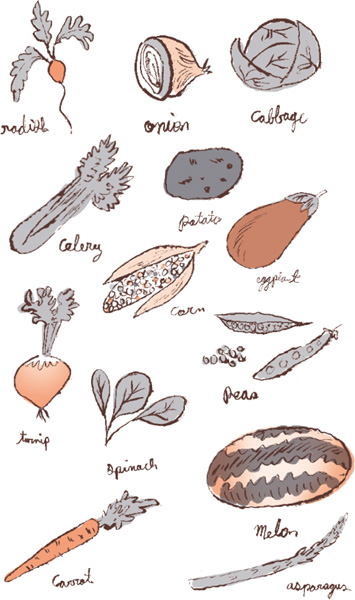

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Vegetables In and Out of the Garden

CHAPTER ONE

In Which Asparagus Seduces the King of France

CHAPTER TWO

In Which Beans Beat Back the Dark Ages

CHAPTER THREE

In Which Beets Make Victorian Belles Blush

CHAPTER FOUR

In Which Cabbage Confounds Diogenes

CHAPTER FIVE

In Which Carrots Win the Trojan War

CHAPTER SIX

In Which Celery Contributes to Casanovas Conquests

CHAPTER SEVEN

In Which Corn Creates Vampires

CHAPTER EIGHT

In Which Cucumbers Imitate Pigeons

CHAPTER NINE

In Which An Eggplant Causes a Holy Man to Faint

CHAPTER TEN

In Which Lettuce Puts Insomniacs to Sleep

CHAPTER ELEVEN

In Which Melons Undermine Mark Twains Morals

CHAPTER TWELVE

In Which Onions Offend Don Quixote

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

In Which Peas Almost Poison General Washington

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

In Which Peppers Win the Nobel Prize

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

In Which Potatoes Baffle the Conquistadors

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

In Which Pumpkins Attend the Worlds Fair

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

In Which Radishes Identify Witches

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

In Which Spinach Deceives a Generation of Children

CHAPTER NINETEEN

In Which Tomatoes Fail to Kill Colonel Johnson

CHAPTER TWENTY

In Which Turnips Make a Viscount Famous

INTRODUCTION

Vegetables In and

Out of the Garden

Did you ever know anyone who was not delighted by a garden?

JOHN SANDERSON

N ineteenth-century gardener Samuel Reynolds Hole, Dean of Rochester, dwelling cheerfully on the subject of his craft in 1899, wrote:

I asked a schoolboy, in the sweet summertide, What he thought a garden was for? and he said, Strawberries. His younger sister suggested Croquet, and the elder Garden-parties. The brother from Oxford made a prompt declaration in favor of Lawn Tennis and Cigarettes, but he was rebuked by a solemn senior, who wore spectacles, and more back hair than is usual with males, and was told that a garden was designed for botanical research, and for the classification of plants. He was about to demonstrate the differences between Acoty- and Monocotyledonous divisions, when the collegian remembered an engagement elsewhere.

Nowadays theres no better agreement on the purpose of gardens. According to the latest poll sponsored by the National Gardening Association in Burlington, Vermont, a gourmet 58 percent of respondents garden for better-tasting food; a thrifty 54 percent garden to save money; a worried 48 percent cite food safety concerns; and a generous 23 percent garden so that theyll have food to share. Exercise, after healthful food, was among top reasons for gardening, according to a University of Illinois survey the figure-conscious pointed out that an hour of moderate digging burns off a waist-whittling 300 calories.

Nobody mentioned fun, though it would be nice to think that the unclassifiable 9 percent in the NGA poll who listed their gardening reasons as Other are lighthearted fans of strawberries and croquet.

All told, such gardeners make up nearly half of all American households, a grand total of forty-three million home vegetable gardens. Top vegetable in these gardens, by a considerable margin, is the tomato, followed in dwindling order by cucumbers, peppers, beans, carrots, squash, and onions. All grow pretty well for us, too: nationally, home vegetable gardens generate an annual 21 billion dollars worth of food, which is no mean feat in these tricky times when every stray billion counts.

Vegetables, just as our mothers told us, are good for us. In fact, theyre essential. Fruits and vegetables, according to various estimates, supply 90 percent of our daily allotment of vitamin C, 50 percent of vitamin A, 35 percent of vitamin B6 25 percent of magnesium, and 20 percent each of niacin (B3), thiamine (B1), and iron. A diet heavy in vegetables reduces risks of cancer and cardiovascular disease, prolongs life expectancy, and makes us skinnier. And as author Michael Pollan points out, vegetables unlike a lot of the questionable processed, manufactured, and additive-laden stuff found today in supermarkets are real honest-to-God food.

For a substantial chunk of human history, however, a lot of people have turned their noses up at vegetables. In Europe, vegetables unflatteringly dubbed rude herbs and roots have a long history of disdainful neglect, with the exception perhaps of the ubiquitous onion. Medieval peasants made do for the most part with grain porridges and cheese, while their social superiors feasted carnivorously on swan, crane, and peacock, piglet draped in daffodils, chicken doused in almond milk, quail, partridge, pigeon, rabbit, venison, and veal.

Nutritionally, theres a lot to be said for crane, peacock, and roasted rabbit. Protein analyses show that meat, in terms of supplying our necessary amino acids, is a nearly perfect food, almost the equivalent of that nutritional gold standard, the egg. The Neanderthals subsisted nicely on red meat, and Methuselahs steady diet of it supported his legendary lifespan of 969 years.

Next page