Contents

Guide

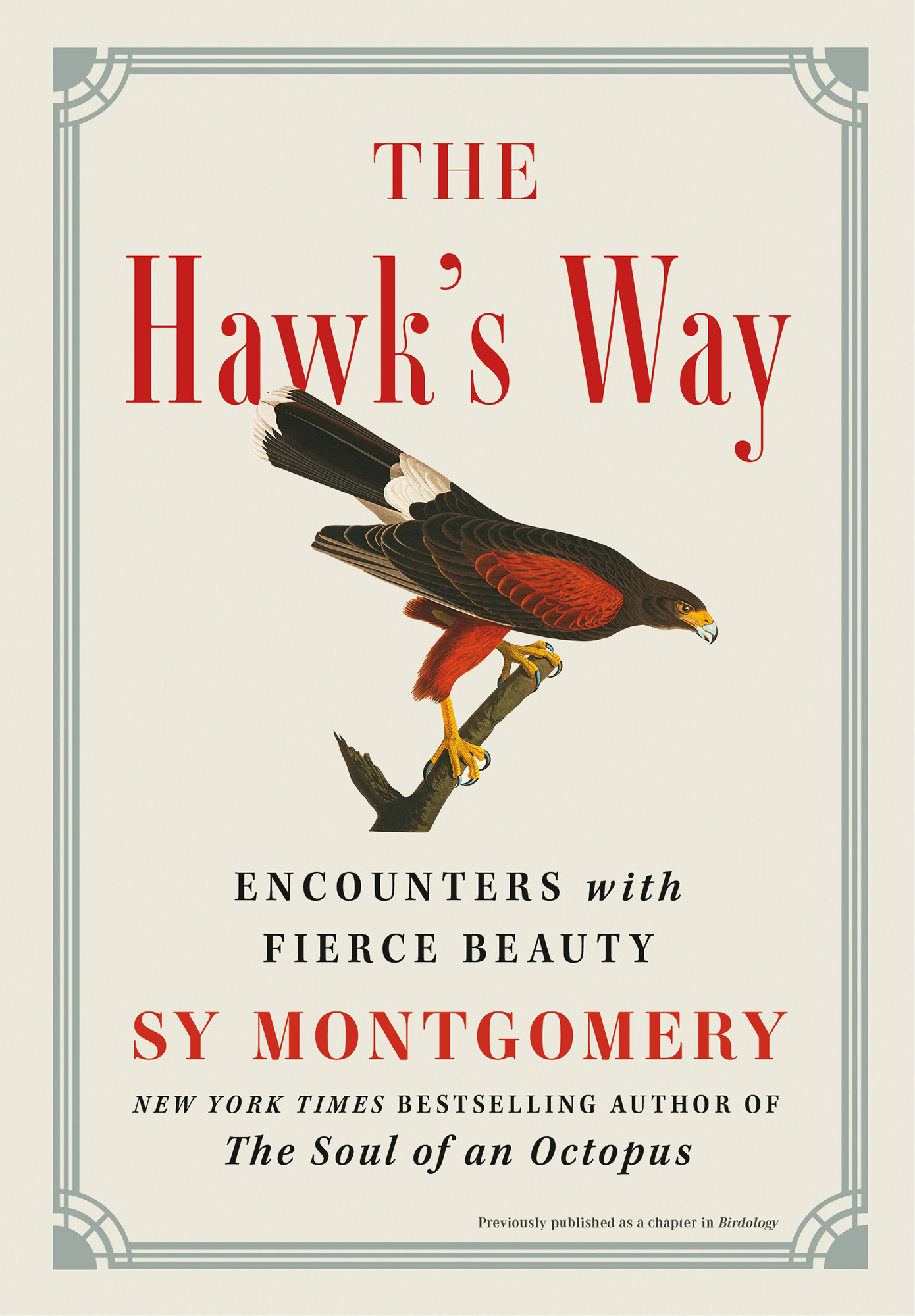

The Hawks Way

Encounters with Fierce Beauty

Sy Montgomery

New York Times Bestselling Author of The Soul of an Octopus

Previously published as a chapter in Birdology

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

An earlier version of this material appeared as a chapter in Sy Montgomerys book Birdology (2010).

Birds Are Fierce from Birdology copyright 2010 by Sy Montgomery

Introduction copyright 2022 by Sy Montgomery

Insert photography Tianne Strombeck

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Atria Books hardcover edition May 2022

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Dana Sloan

Jacket design by Laywan Kwan

Jacket photograph Natural History Museum, London/Bridgeman Images and Adobe Stock

Author photograph by Tianne Strombeck

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022932952

ISBN 978-1-6680-0196-7

ISBN 978-1-6680-0197-4 (ebook)

In loving memory of Nancy Cowan

March 12, 1947January 8, 2022

master falconer, wise in the way of the hawk

INTRODUCTION

I nches from my face, I hold a living dinosaur.

Like his ancestors, the creature I hold on my fist is a hunter, an eater of meat. His forebears, the theropod dinosaurs, included some of the most fearsome creatures to walk the earth: Allosaurus, Velociraptor, and Tyrannosaurus. Like them, he is a bipedal predator. Like them, he possesses large finger bones, and forward-facing eyes bestowing excellent binocular vision. Like them, when he hatched out of the egg, he was covered with down. As with many of them, his baby down then gave way to feathers.

The difference is, unlike the other dinosaurs, the one before me can fly.

His name is Mahood. Hes a young Harriss hawk, a species native to the American Southwest, with bold feather markings of mahogany brown, chestnut red, and white, and long yellow legs, his feet tipped in curved, obsidian talons. In August, he was transported from the breeder where hed hatched in upstate New York to take up residence with my friend and neighbor, Henry Walters, a poet, parent, and master falconer.

Mahood and I are meeting for the first time. He has not yet learned how to hunt. Henry is trying to teach him. Henry wants Mahood to get used to being around people, which is why hes asked me to grab my falconry glove and come over.

Mahood consents to perch on my glove. But the next moment, without any warning, he turns his head, looks into my eyes, opens his yellow, razor-sharp beak, and screams, full force, into my face.

Mahood does not like me, and is not shy about announcing this. His is not a scream of fear but of fury: the voice of an angry dinosaur. All birds, we now know from fossils and DNA, are, in fact, what became of the reptiles who once ruled the earth, creatures we all used to think were extinct. That they are not is a truth that Darwins champion, Thomas Huxley, suspected as early as 1867; he called birds glorified reptiles. But the connection between birds and dinosaurs is impossible to miss in a raptor.

My husband, watching from a comfortable distance, is alarmed by Mahoods scream. Hes used to seeing strange dogs and cats, pigs and chickens, horses, and even an octopus, relax to my touch. But I am not surprised at all by Mahoods reaction. Hawks, as I now know well, are different.

My falconry instructor, Nancy Cowan, made this clear from the start: A hawk does not want you to touch it. It does not want to be petted. Ever. Not even a hawk you have raised from a hatchling and fed from your hand. Eventually, some hawks will, under certain circumstances, consent to your touchbut they dont like it. A single mistake handling a raptor, even one you know well, may provoke it to bite you, stab its talons into your flesh, or both.

Sometimes a hawk youve worked with for months or even years will attack. Henrys previous hawk, a big female redtail, Mary, one day flew out of a tree and, instead of landing on his glove, strafed his ear, slicing through the cartilage with her outstretched talons. The upper part of his ear flopped over like a Labradors. (Emergency room doctors braced it so it would heal upright again.) Why? We never knew. (My husband sent me out with a hard hat the next time I flew her with Henrybut I left it behind, because many hawks dislike hats and scream at you till you take it off.)

Hawks do not play by our rules. You can never assume that a hawk, even one you raised from a chick, will forgive your mistakessometimes a single error ruptures the relationship forever. A hawk will not come to your rescue if youre in trouble. A hawk will not comfort you if you are sad. What a falconry hawk will do, if you do everything right, is allow you to be their hunting partnerthe junior partner, Nancy is quick to point out, for the hawk, with its exquisite vision and lightning responses, is always the superior hunter.

Its a funny kind of relationship you have with a hawk, Henry tells me weeks later. We are walking through the forest, and Mahood is keeping pace with us, flying overhead, then perching on tree limbs, looking down and keeping track of us below, what falconers call following on. Mahood is still immature, and Henry is well aware of the responsibility he bears for nurturing this young soul. But what is the nature of the bond you can share with a raptor?

Its confusing, says Henry. Its love, but all mixed up with nerves and hunger and the hunthuman love, trying to keep up with superhuman things. Its not like any other relationship you have with anyone else.

If you do everything right, a hawk will allow you to act as its servant. And for this, the falconer is profoundly grateful.

The birds of prey preserve an ancient, primal wildness, conserved in their kind since the beginning of the world. And its exactly for this reason that, more than a decade after my first experiences with falconry, which I will share in the following pages, I still come back for more. I am still learning.

Today, the birds I first flew are gone, but I have come to know their successors, and enjoy flying them. Im thrilled Mahood is living on our street and plan to join Henry flying him often. And I am always looking overhead for raptors, listening for the wild and savage sound of their voices.

I am drawn, and expect I always will be, to the company of hawksto be bathed, like a baptism, in the presence of their fierce, wild glory.

Just like friendships with different people, relationships with individuals of other species have lessons to teach us. We are, of course, deeply enriched simply by learning about lifeways other than our own: I love it that some creatures Ive been privileged to know can taste with their skin (octopuses), see with sound (dolphins and bats), and perceive colors we cant even imagine (birds and some reptiles). But animals also have much to show us about how we, as humans, can more meaningfully and compassionately encounter the wider world.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.