All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file.

Lions arent the only excitement in the Serengeti.

Chapter One

The grass is the color of lions. If the big cats werent lying so close to the road, theyd be invisible. Thick manes frame two massive heads, marking them as adult males; the third is a lioness. Though their yellow eyes seem as indifferent as the sun, they are probably watching the same thing we are: a herd of fifty wildebeests about three hundred yards away from our Land Cruiser.

A nine-month-old calf cries plaintively: Nyeh! Nyeh! Hes lost his mother. Though the adults pronounce it somewhat differently (Neeh! Noo! Neeh! Noo!) the calf almost sounds like hes calling out the wildebeests other common name: Gnuuu! Gnnuuu!

If the lions notice the lost calf, they might become active, says wildlife biologist Dick Estes, the leader of our safari. But when one of the lions rises, its a different drive he seeks to satisfy. He saunters over to the female and straddles her. He gives a few thrusts with his hips, but after five seconds, he gives up.

I dont think they got it on, comments Liz Thomas. As a teen, she lived among lions in Namibia, and knows that lion lovemaking typically lasts longer than thatand ends with a swat and a snarl from the lioness. Thats for good reason. The male has tiny barbs on his penis. But this lioness doesnt grumble; she flips over on her back, legs folded in the air, playful in the way of a sleepy puppy. The male returns to his other companion, who is probably his brother. He lies back down.

For now, the action is over. But other safari vehicles begin to gather. Lions are one of Africas big five (the others are elephants, rhinos, Cape buffaloes, and leopards) that big-game hunters once sought as trophies, and that most tourists want to see today. Soon eleven cars are idling by the road.

This is my nightmare, says Dick. A crowd of vehicles watching lions do nothing, ignoring all the REAL excitement!

Just past the lazing lions, the fifty wildebeests are engaged in dramas of life and death. They are advertising territory. Theyre seeking mates. Theyre finding the food that they need to sustain them on one of the greatest animal journeys on earth.

The lost calf reunites with his mother and rushes to her udder to suckle. A young bull chases a rival, whose right horn was broken in combat. Theres so much going on! says Dick.

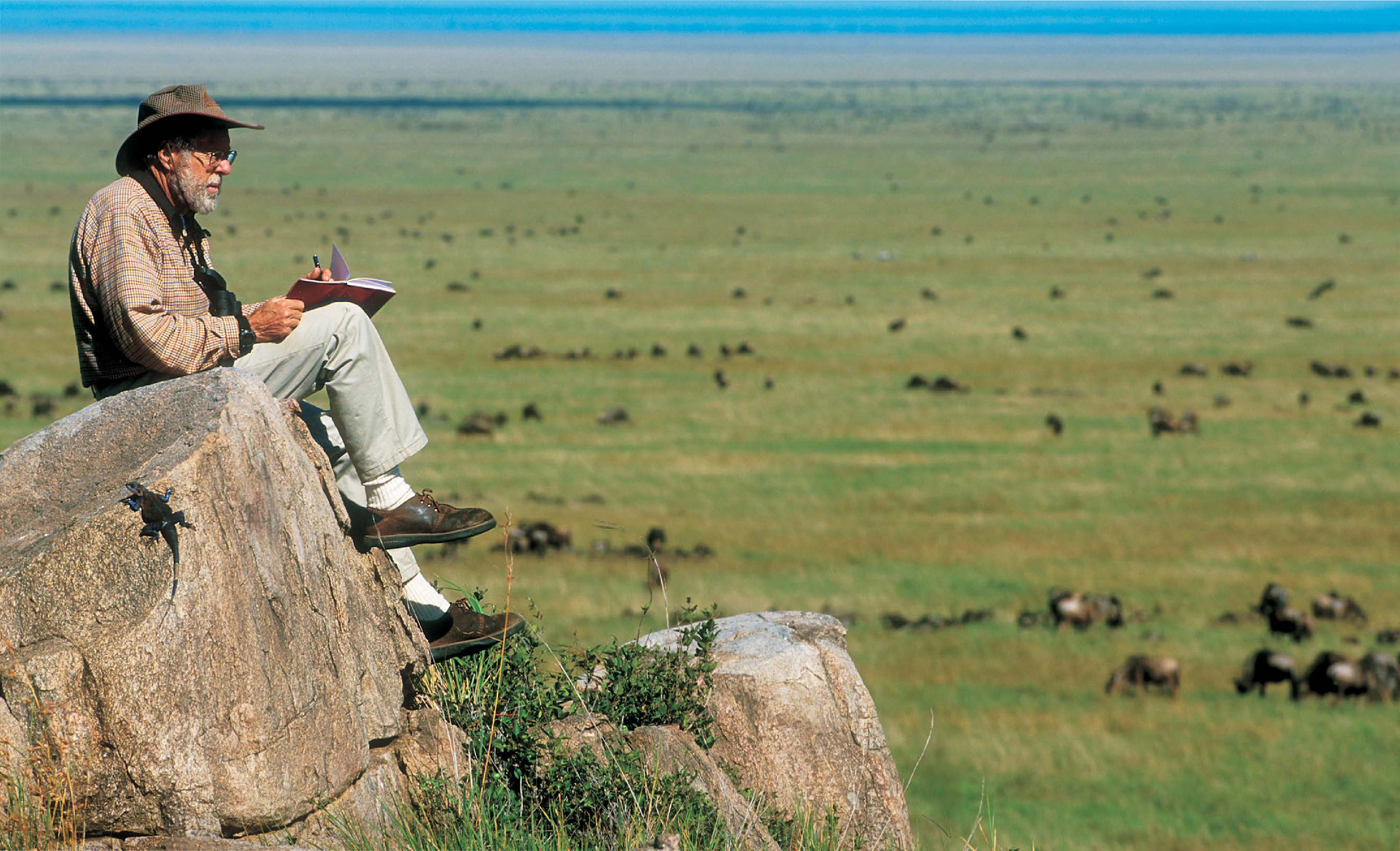

The guru of gnu, DR. RICHARD DESPARD ESTES. Though he set his sights on Africa as a child, Dick took a circuitous route to get there. Graduating from Harvard in 1950 with a degree in sociobiology, he worked mainly as a writer till he got a chance to do a two-year survey of wildlife in Burma in 1958where, among other adventures, a tiger investigated his tent one night. Upon his return to the United States, he enrolled at Cornell University for graduate school and proposed an ambitious multi-species study of five hoofed species of animalselands, zebras, Thompsons and Grants gazelles, and wildebeestsin Ngorongoro Crater. But wildebeests took up most of his time. They still do.

Dick has also conducted pioneering fieldwork on other antelope species, including years of study of the magnificent scimitar-horned sable and giant sable in Kenya and Angola. From 1978 to 2006 he chaired or cochaired the Antelope Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature; he is a founding member and trustee of the Rare Species Conservatory Foundation, which designs protection and reintroduction programs for endangered species in the wild, and is especially proud that he helped repatriate the American-bred bongo, a beautiful striped antelope, to Kenya. But his heart belongs most of all to the wildebeests. For more than half a century, Dick has been acknowledged around the world as the wildebeests most ardent and respected champion.

But not many people know how to see it.

Dick doesand thats why were here. My friend of thirty years, Dr. Richard Despard Estes has been studying these powerful, high-shouldered, bearded antelopes for more than half a century, longer than any other scientist who has ever lived.

From his white beard to his bush hat to his twinkling blue eyes, Dick looks as if he stepped out of Central Casting for the part of African wildlife biologist. The undisputed guru of gnu, hes acknowledged the world over as the top expert on wildebeests. And though lions may seem more glamorous, its wildebeests who drive the ecology and evolution of the largest savanna ecosystem in the world.

Like no other event in nature, the wildebeest migration defines wild Africa.

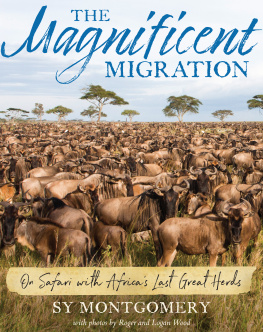

The extravagance of their number stupefies: one and a quarter million wildebeests, in separate herds of tens of thousands, all on the move at once, accompanied by hundreds of thousands of zebras and gazelles. It is the largest mass movement of animals on land.

The sheer number of so many animals in motion is more than a dazzling spectacle. It is a force like gravity, or rainfalla force that transforms, nourishes, and renews both the lands over which they travel and the other creatures who gather in their wake.

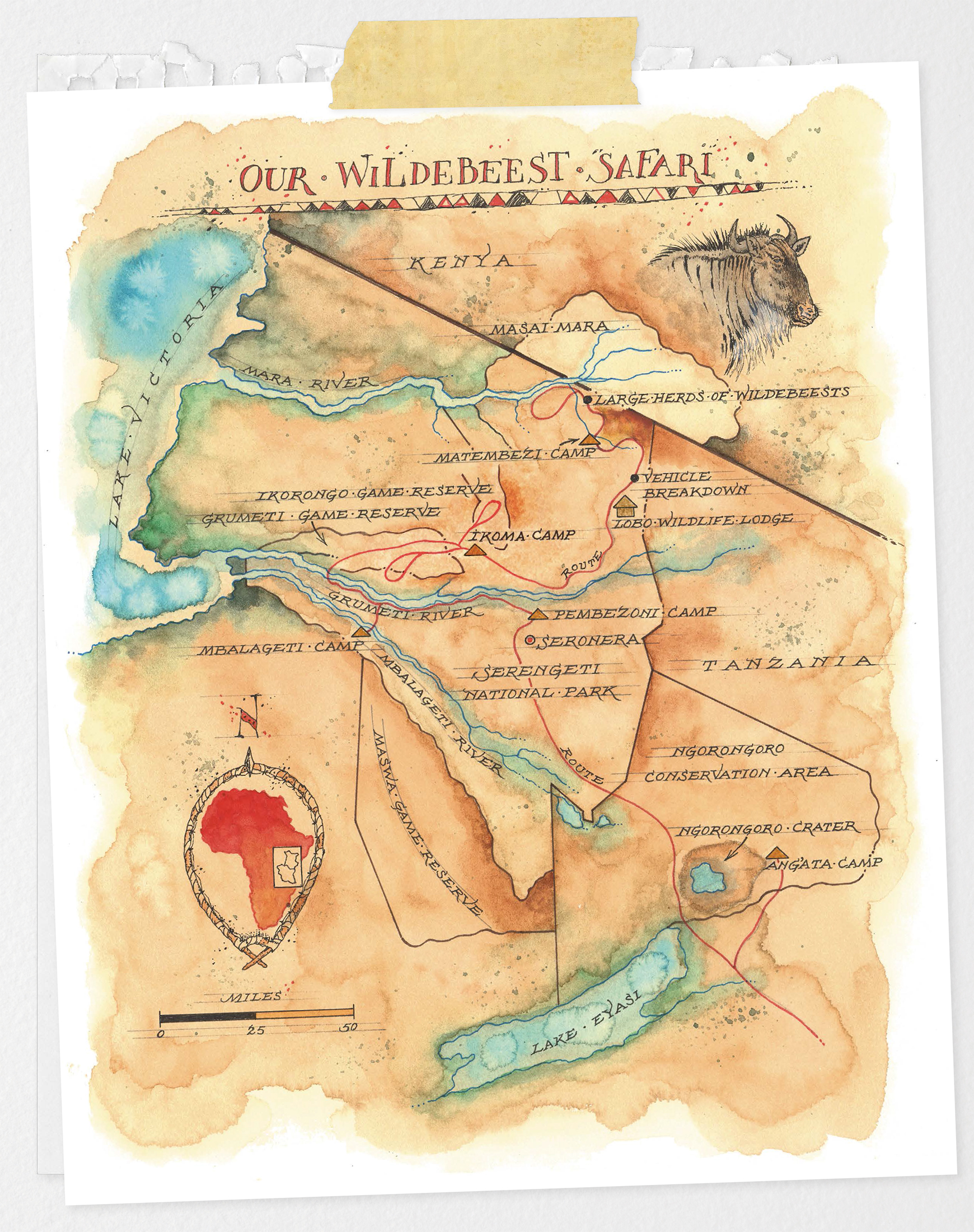

The movements of the wildebeests are described in terms normally reserved for oceans or weather systems: They storm across rivers and lakes, dodging the jaws of crocodiles. They tumble down cliffs like waterfalls. They pour into the greening plains. The wildebeests follow the rains and the nourishing grasses in a roughly clockwise route of nearly a thousand miles, from Tanzania to Kenya, year-round. On their journey, they collect an unrivaled entourage of two hundred thousand zebras, five hundred thousand Thompsons gazelles, eighteen thousand elands, ninety-seven thousand topisas well as the host of lions, leopards, jackals, hyenas, and vultures who eagerly await their arrival in their home territories.

This is the greatest of all mammalian migrations, Dick tells me. To be part of something that huge is an amazing feeling. And this is the quest that has drawn us here, on this Friday in late June, to Tanzanias Ngorongoro Crater. This is the gateway to Africas great Serengeti plains, and part of the vast Serengeti-Masai Mara ecosystem of roughly twenty-five thousand square milesthe size of Connecticut and Rhode Island combined.