Table of Contents

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

POETRY

Alibi

Summer Snow

Angel

Fusewire

Rembrandt Would Have Loved You

Voodoo Shop

The Soho Leopard

Darwin: A Life in Poems

ABOUT POETRY

52 Ways of Looking at a Poem

The Poem and the Journey

Silent Letters of the Alphabet

Alfred Lord Tennyson: Selected Poems with

Introduction and Notes (editor)

Sir Walter Ralegh (Poet to Poet series)

FICTION

Where the Serpent Lives

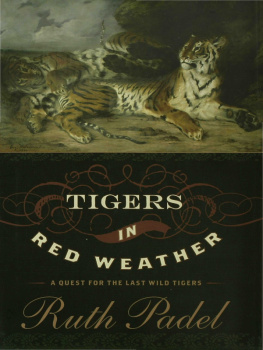

NON-FICTION

In and Out of the Mind: Greek Images of the Tragic Self

Whom Gods Destroy: Elements of Greek and Tragic Madness

Im a Man: Sex, Gods and RocknRoll

Tigers in Red Weather

For Pedro, Gisa, Bruno and Mia

Acknowledgments

This book, travel for it and time to write it, was made possible by an Individual Artists Award from the Arts Council of England for which I am very grateful. Many warm thanks also to the Environment Institute and History Department of University College, London, for a Resident Writers Fellowship, which enabled me to finish it. Enormous thanks to David Harsent for his editing of the poems, and to Ian Pindar for his copyediting.

I have discussed migration with many people for many years and am very grateful to them all for their responses, especially those who gave their time and expertise to comment on the prose. They include Phillip Birch, Tim Birkhead, Kathleen Burke, Gwen Burnyeat, Mark Cocker, Elaine Feinstein, Eva Hoffman, Kerin Hope, Aamer Hussein, Sanjay Iyer, Sushrut Jardav, Lauro Martines, Jeremy Mynott, Michael Oberts, Sigrid Padel, Arshia Sattar and Tom Schuller. Many thanks also to people who gave material which sparked things off, especially Peter Conradi, Ruth Fainlight, Caroline Moorehead, Elizabeth Nabarro, Felix Padel and Alexa Walker.

Thanks to Susie Symes for an inspiring introduction to the Museum of Immigration at 19 Princelet Street, to Mark Baldwin for an invitation to watch Ballet Rambert rehearse and talk to the dancers, to D. V. Girish of Bhadra Wildlife Conservation Trust for guidance in the forest over many years (also for the Rufous Turtle Dove), to Andrew Morley for genetics and Claudio Scazzocchio for Lessespian migration.

I should like to thank the Wellcome Trust for a commission to write the text for Music from the Genome, Somerset House Resident Writers Programme for an invitation to talk on Bruegels Landscape with Flight into Egypt at the Courtauld Gallery, and the Kate OBrien Conference, Limerick, for an invitation to give an address on the theme of outsiders, which helped me shape reflections on the key figure of John James Audubon.

Thanks also to editors who published some of these poems in Acumen; Arvon Poetry Competition Winners 2006; Barque Bernaque (Poems commissioned by Newcastle Centre for the Literary Arts to accompany The Cultural Life of Barnacles Exhibition at the Great North Museum Newcastle, 2009 ); Best British Poetry 2011; the Guardian; Hortus; interLitQ.org; London Review of Books; The New Humanist; New Statesman; New Welsh Review; The New Yorker; Poetry Review and The Wolf. Also to Sonja Patel, editor of the anthology Nature Tales: Encounters with British Wildlife (2010) where some prose passages were first published. Earlier versions of three poems appeared in my previous collections Angel (Bloodaxe, 1993), Fusewire (Chatto, 1996) and Voodoo Shop (Chatto, 2002).

I cant thank my editors, Parisa Ebrahimi and Clara Farmer, enough for their advice and support. Parisas fine judgement, patience, kindness, vision and clear head made sure that whatever trees we wandered among, we never lost sight of the wood.

On Migration

Ripples on New Grass

When all this is over, said the princess,

this bothersome growing up, Ill live with wild horses.

I want to race tumbleweed blowing down a canyon

in Wyoming, dip my muzzle in a mountain tarn.

I intend to learn the trails of Ishmael and Astarte

beyond blue ridges where no one can get me,

find a bird with a pearl inside, heavy as ten copper coins,

track the luminous red wind that brings thunder

and go where ripples on new grass shimmer

in a hidden valley only I shall know.

I want to see autumn swarms of monarch butterflies,

saffron, primrose, honey-brown, blur sapphire skies

on their way to the Gulf: a gold skein

over the face of Ocean, calling all migrants home.

Migration Made the World

You really feel the earth turn in September. The planet is sliding us into autumn. On the other side of the equator it must be sliding everyone into spring, but here every morning seems a little darker.

I come into the kitchen and see starlings round the bird-feeders outside. Dawn glows through the geisha fans of their wings as they try to eat and flutter at the same time. One of them does it by hanging upside down and sticking its tail over its head. They may live in London the whole year but they could have flown across the English Channel last night. Starlings are partial migrants some migrate, some dont. Huge flocks arrive every autumn on Englands east coast and radiate out to join other starlings across the country. In spring, hundreds of thousands go back to nest in Eastern Europe.

We were all wanderers once. We walked out of Africa looking for food, safety, water, shelter and territory. Travelling was where we began and Homo viator, man the pilgrim, life as pilgrimage, is deep-engrained in Western thought. Mediaeval Christianity said we were strangers in this world, searching for the spiritual homeland to which we originally belonged. We werent meant to be here we were put in a garden. But that went wrong and now we are wanderers between two worlds, wayfarers on the via, the way, of life.

Human beings are both fixed and wandering, settlers and nomads. Our history is the story of the nomad giving way to the settler but when people are unsettled they have to migrate. The point of migration, whether you are a starling or a human being, is to reach whatever helps you and your children live in a new place. Home and migration belong together, two sides of the same ancient coin. Home is something we make, then things change, either in ourselves or in the world, we lose home and have to go elsewhere.

The word migrate covers many sorts of move. It comes from the Latin migrare, to move from one place to another, and is related to mutable and the Greek ameibein, to change. We use it for two types of journey. Both can be undertaken either by large groups or individuals on their own. The two have a lot in common, but there is a wide spectrum of activity between.