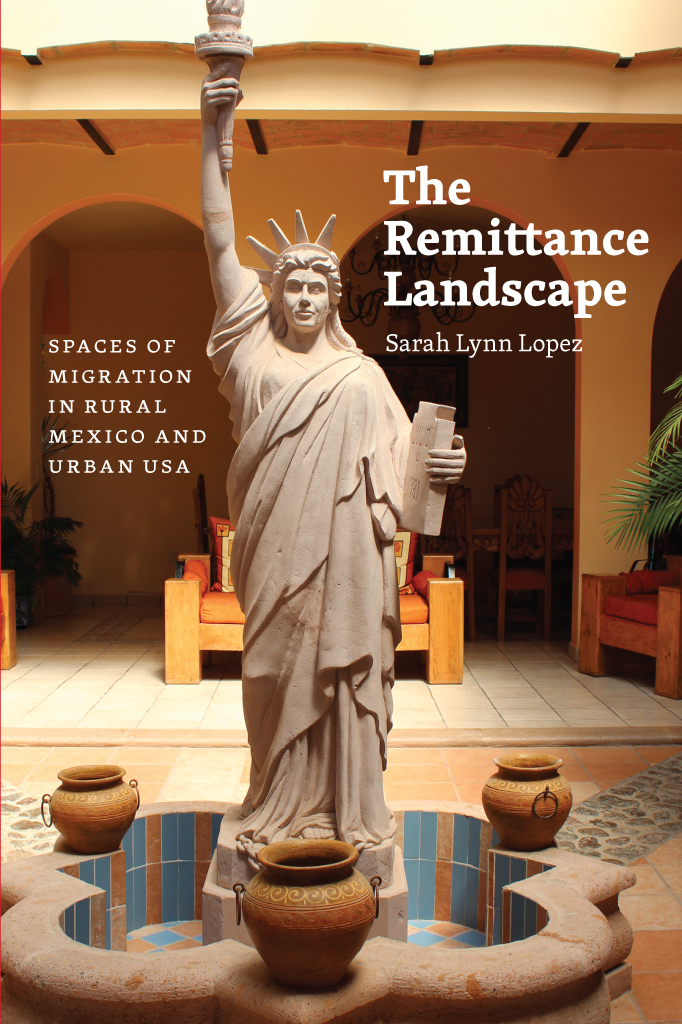

The Remittance Landscape

The Remittance Landscape

Spaces of Migration in Rural Mexico and Urban USA

Sarah Lynn Lopez

University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

Sarah Lynn Lopez is assistant professor in the School of Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2015 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10513-0(cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-20281-5(paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-20295-2(e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226202952.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lopez, Sarah Lynn, author.

The remittance landscape : spaces of migration in rural Mexico and urban USA / Sarah Lynn Lopez. 1 Edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-10513-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-226-20281-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-226-20295-2 (e-book) 1. Emigrant remittancesMexico. 2. MexicansUnited States. 3. MexicoEmigration and immigration. I. Title

HG3916.L674 2014

332.042460972dc23

2014020844

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Chesney

Contents

Buildings as Evidence of Social Change

Dream Homes at a Distance

The Spatial Legacy of Remittance Policy

The Gendered Spectacle of Remittance

Norteo Institutions Transform Public Space

Transnational Landscapes for Aging and Dying

Remittance Urbanism in the United States

This book began in a small caf kitchen in Berkeley, California, where I worked as a cook with three migrants from a village near Leon, the capital city of Guanajuato, Mexico. Over time, I learned about their aspirations to build new homesnot in Berkeley but in their hometowns. My coworkers earned meager salaries, lived in cramped apartments in Oakland, and had been in California for over a decade. Why, then, were they investing in new homes in rural Mexico? As a historian of the built environment, I was curious about the homes themselves. What did they look like? Who built them? How did my coworkers (undocumented Mexican migrants who did not travel home) manage the construction process from a distance?

Upon further reflection, this book began long before I ever spoke with my coworkers about their uninhabited dream houses. I am the product of the aspirations, ambitions, and discomfort that come from such spaces of migration. My mother is a Cuban Jew, born and raised in Havana, whose parents had fled Poland and Romania in the early 1930s. My fathers family made their pilgrimage in the 1950s from a Chihuahuan mining pueblo in Mexico to strawberry fields in south Texas and ultimately to the mining and refinery town of Trona in the Mojave Desert. I grew up reflecting on how processes of migration, with the necessary adjustment to radically new and different contexts, shape ones experience of everyday life. This project builds on such reflections, investigating what the spaces of migration mean for migrants themselves.

To research the architecture of migration, I interviewed migrants who conceived of, funded, and managed remittance construction. This initially took me, in 2004, to the north-central mountain state of Guanajuato, where I spent a summer with my coworkers from Berkeley, collecting life histories and drawing plans of their houses. Years later, I began research on the central bajo state of Jaliscothe subject of this book. I chose Jalisco for two reasons: One, it is a state that Paul S. Taylor and Manuel Gamio researched in the 1920s and 1930s, during which time they recorded a few important examples of how the built environment of Jalisco was transformed by migration at that time. And two, due to the long history of emigration from Jalisco to California and elsewhere in the United States, Jaliscienses have been sending remittances to finance homes for almost a century, and they are well organized in migrant hometown associations ( HTAs) that finance public projects. Starting in California, I contacted HTA members associated with the Federation of Jaliscienses, who invited me to their pueblos to see what they had accomplished, acting as town boosters. The president of the Federation of Jaliscienses in 2007, Salvador Garca, identified eight towns for me to visit that had particularly impressive remittance projects. During my first two months in Jalisco, I visited twenty-three pueblos, of which only two appeared to be unaffected by remittance-financed building projects. Out of the twenty-one pueblos with evident remittance construction, I was drawn to three in the south of the state that had ambitious, distinct, and well-developed projects. The rodeo arena in Lagunillas, the cultural center in San Juan, and the old age home in Los Guajesall on Garcas listwere dramatic, typologically distinct interventions in previously homogeneous and traditional building fabrics. These public architectures, unlike my coworkers dream houses in Guanajuato, were not only modern, symbolic of the success of migration, but also spaces consciously intended by their patrons and sponsors to bring about social and economic change in their hometowns.

Throughout the process of researching and writing this book, I have become an interdisciplinary scholar. As an architectural and urban historian, I was always interested in the material history of migration, yet I quickly found that I could not write about remittances (or better yet, remittance landscapes) without understanding contemporary development policy and the sociology and anthropology of migration. While my primary interest still lay in the history of how migration shapes places, when I started this project in 2006, little had been written on the Mexican governments 31 program. In order to understand the architectures resulting from this program, I extended my work beyond the world of the built environment to explore the Mexican governments development policy and how it influenced individual and familial social relations in rural Mexico. Finally, my theory of remittance spaceexplained in the introduction to this bookprovokes questions about the mutual constitution of cities and distant rural hinterlands as part of a transborder continuum, many of which remain unanswered. In this book I argue that migration creates remittance landscapes, that migrants live in remittance spaces. The book aims to set the stage for future research on remittance landscapes and spaces across disparate migration streams. Further research is required to understand the history of how remittances have been used throughout the twentieth century, evolving remittance building styles, and the history of Mexican urbanization, modernization, and development in relation to the built environment of small towns and midsized cities.

Exploring the processes that shape places, architectures, and people required me to interact with how development discourses, economic policy, and the form and meaning of ordinary architecture in rural Mexico interface with one another. After hundreds of interviews and informal discussions with Mexican migrants and their families in Mexico, I am convinced that the experts on remittances, development, and Mexican building construction are migrants themselves, from whom I am continually learning and to whom Im deeply indebted.

This project would not have happened without the assistance of several coworkers and friendsMexican migrants from Guanajuato, Michoacn, and Jaliscowho opened their homes to me and shared their life stories with me. Individuals in Jalisco and members of hometown associations from Jalisco and Michoacn in both Chicago and Los Angeles have been extremely generous with their time and patient with my questions.