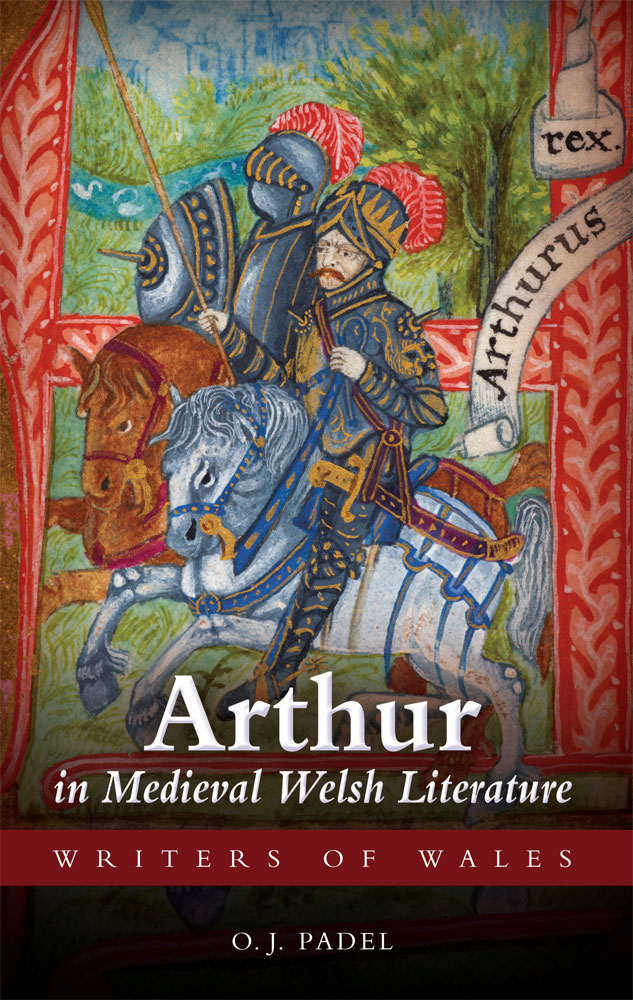

Writers of Wales

Arthur in Medieval Welsh Literature

Editors:

Meic Stephens

Jane Aaron

M. Wynn Thomas

Honorary Series Editor:

R. Brinley Jones

Other titles in the Writers of Wales series:

R. S. Thomas (2013), Tony Brown

Kate Roberts (2012), Katie Gramich

Ruth Bidgood (2012), Matthew Jarvis

Geoffrey of Monmouth (2010), Karen Jankulak

Herbert Williams (2010), Phil Carradice

Rhys Davies (2009), Huw Osborne

Writers of Wales

Arthur in Medieval

Welsh Literature

O. J. Padel

| University of Wales Press Cardiff 2013 |

O. J. Padel, 2013

Originally published in 2000

New edition published 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Applications for the copyright owners written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the University of Wales Press, 10 Columbus Walk, Brigantine Place, Cardiff CF10 4UP

www.uwp.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN978-0-7083-2625-1

eISBN978-1-78316-569-8

The right of O. J. Padel to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77, 78 and 79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Cover image: Detail of initial A from a charter of King Arthur (copy dated 1587). Cambridge University Archives, MS Hare A.1, fol. 1r. Reproduced by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library

Contents

This book first appeared twelve years ago and it has been suggested that a reprint would be useful. Naturally further work has been done in the meantime, but it has not significantly affected the discussions given here. So the text has not been altered, but a supplementary bibliography enables readers to take subsequent work into account, and an index has been added. I am grateful to Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan for her help, and to the University of Wales Press for undertaking the reprint.

O.J.P.

Several people have helped by discussion and in other ways. I particularly thank Dr Brian Golding, Dr Nerys Ann Jones, Michael Polkinhorn and Professor Brynley Roberts; also several former students, especially Jonathan Coe, Anna Langford and Barry Lewis; and an anonymous reader for the Press; but none of them should be implicated in the views expressed here.

This book is about Arthur as a literary figure in medieval Wales. It is not about the Arthur of history, if there was such a person. It is widely assumed that the legendary figure was derived from a historical one, but it is equally possible that the seemingly historical Arthur was created by the historicization of a figure of legend. The legendary figure of Arthur was remarkably consistent in local British folklore for over a thousand years, from its first appearance in the ninth century to folklore current in the nineteenth; but learned authors, the intermediaries through whom we have received our knowledge of early Welsh traditions, sometimes gave their own interpretations of the character either for their own reasons or because they knew of Arthurs wider literary reputation rather than giving a close portrayal of the traditional figure. For this reason it is essential, when studying the portrayal of Arthur in a particular text, to try to understand the nature and purpose of that text; yet the understanding of individual texts is naturally a subjective matter. The nature of the literary works therefore receives particular attention in the pages which follow, even though space here cannot allow for all the different interpretations that have been offered of some of the better-known texts.

Wales has no monopoly of the Arthurian legend. Although the earliest mentions of Arthur are found in the ninth-century Welsh-Latin HISTORIA Brittonum (The History of the Britons), he also occurs in similar contexts in Cornwall, southern Scotland and Brittany, as soon as there are records of a kind liable to show the local folklore which was his particular domain. For our purpose the important point is not whether he was based on a historical person (for no records survive capable of answering that question), but the fact that in the early Middle Ages, by the twelfth century at the latest, he was renowned in local storytelling wherever Welsh and its sister languages were spoken.

The earliest datable text mentioning Arthur is in Latin, the HISTORIA BRITTONUM formerly attributed to Nennius. This was probably compiled in north Wales in the years 82930. It is worth recalling, in passing, the notable absence of Arthur from an earlier Latin work, Gildass DE EXCIDIO BRITANNIAE (On the Ruin of Britain), composed in the sixth century. Gildas gave a historical summary of the English takeover of Britain, and if Arthur had played a major part in the British resistance we might well have expected Gildas to name him, as he does Ambrosius Aurelianus. Likewise, Arthur is absent from Bedes ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY oF THE ENGLISH People, written about a century before the HISTORIA BRITTONUM, though in Bedes case other reasons for his silence might be envisaged.

Given that the HISTORIA BRITTONUM, dating from the ninth century, is the earliest Arthurian text, its most striking feature is that it contains two different, seemingly contradictory, portrayals of Arthur. One is the often-quoted List of Arthurs battles against the English, where Arthur is depicted as the great military leader (dux bellorum) who led the British kings against the second generation of English settlers. (The context seems to imply that Arthur was not regarded as a king himself.) Twelve battles are specified, at nine sites (four at a single site). The identification of place-names in early documents is dependent upon the context, and this list supplies so little context that safe identification is impossible for the most part; this has made the list a rich quarry for those wishing to locate Arthur in their own particular areas, wherever those may be.

The final battle, Mount Badon, probably in southern England, is no doubt the one named by Gildas who, by implication, attributes the victory instead to Ambrosius Aurelianus. A few other battle sites are also recognizable from Welsh legend: that at the River Bassas recalls Baschurch in the Welsh Marches, named in the englyn poetry concerning Heledd; that at the city of the Legion sounds like the seventh-century battle of Chester where thousands of monks of Bangor were said to have been slaughtered. The only sites also named elsewhere as battles involving Arthur are Badon (also in the Welsh Annals, see p. 8) and the River Tryfrwyd (Tribruit): Arthurs opponent there, we learn from the poem Pa r ywr porthor? (see p. 22), was the legendary Gwrgi Garwlwyd (Man-hound Rough-grey), who used to slay a corpse of the Welsh every day, and two on Saturdays so as not to kill on a Sunday, according to the Triads; he was eventually killed, though not by Arthur, in one of the Three Fortunate Assassinations.