For Keith

Published by Otago University Press

Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2019

Copyright Diane Comer

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

ISBN 978-1-98-853153-3 (print)

ISBN 978-1-98-859214-5 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-98-859215-2 (Kindle)

ISBN 978-1-98-859216-9 (ePdf)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Published with the assistance of Creative New Zealand

Editor: Paula Wagemaker

Index: Barbara Frame

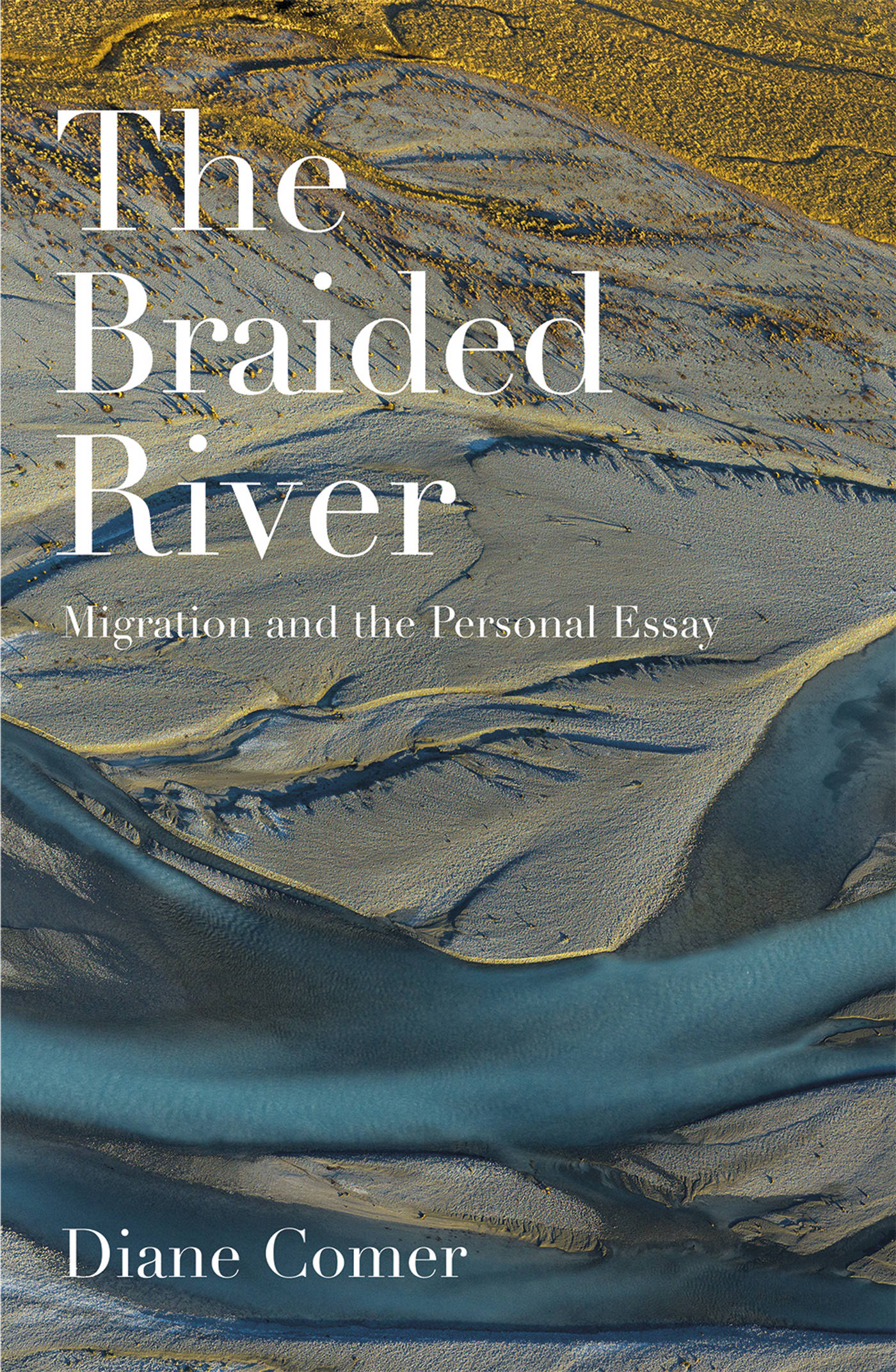

Front cover design: Lisa Elliot

Cover photograph: Randy Hanna

Author photograph: Ebony Lamb

Ebook conversion 2019 by meBooks

Contents

Here is the time for the sayable, here is its homeland.

Speak and bear witness.

Rainer Maria Rilke

A true debt can never be repaid, for which I owe my migrant writers my deepest thanks. This braided river is made possible through the gift of their personal essays, which have carried me across oceans and back again. I wish to thank each of you for your writing, your time and your steadfast belief in this book. Your courage in the face of difficulty sustained me through earthquakes, hemispheric shifts and the loss of language. My gratitude for your generosity and inspiration is past words.

For supporting the research in true transnational fashion, huge thanks to Lyndon Fraser and Jennifer Clement. For listening to me in a dark time, I want to thank Thomas Wright. To my favourite doctoral women, Sonia-Ingrid Anderson, Julie Johnson, Lorraine Ritchie, Lenore Hoyt and Marguerite Tassi, many thanks. For help landing the fish, cheers to the Splinters, with special thanks to Kate for her manaakitanga. To the poets and writers in my life who gave careful consideration to the words, I am grateful to Susan Benner, Coral Atkinson, Dianna Troyer, Bern Mulvey, John Price, Sonia Sundstedt, Harry Ricketts, Laura Klein and my sister Lisa Zimmerman. Heartfelt appreciation to my wonderful editor and friend Paula Wagemaker for her thoughtful editing of the manuscript, what a gift. Other friends supported me with art, letters, books, cups of tea, smacks up the side of the head and sheer belief in me: thank you to Gilaine Spoto, Kathy Kise, Geoff Vader, Daniela Dragas, Wayne Christianson, Andr Krebber, Wendy Logan and dear Brent Johnson. Grateful acknowledgement to my home crew who keep me in the middle of the boat, and especially to Selwyn for the river image.

To our dear friends in Sweden, whose kindness and generosity knew no bounds while we lived there, Inger Pettersson, Vicky Gatzouras, se Nygren, Ulrica Skagert, Jrgen Samuelsson, Jessica Enevold, Anna Svennson-Stening and Micke Dahlberg, tack s mycket. Know you and yours are always welcome in the land of the long white cloud.

To my son and daughter, Kitt and Rilke, thank you for being so patient and understanding throughout the shifts in our lives. May you always know where home is.

Finally, I could never have come to the present without him: the river under the river throughout this journey is Keith, who brought our family back to where we belong.

M y migration to New Zealand began in 2007 when my husband and I, with our two children, left the United States to come to Christchurch. I hated New Zealand at first. Alone, freezing in our rental house while my husband and children were at work and school, I wrote endless emails to friends and family detailing my unhappiness, no doubt putting many of them off visiting us for years. I needed a job, if only to be warm. As is often the case with migrants, my skills went unutilised at first. I felt disheartened not being able to teach at university level as I had done for years in the US and Sweden. I worked at one temporary position after another: receptionist, learning advisor, web page builder, dogsbody. And then I began teaching a community education course on the personal essay.

By chance or choice, the class attracted adult migrants who wrote essays of remarkable depth and scope about their migration experiences. Perhaps the loss of home prompts migrants to want to write, for it is a reality to those with the experience of exile that leaving home, creating absence, and dislocation is essential for the writing act to proceed in the first place, and to become meaningful. I felt a flash of recognition when Gareth, a Welsh doctor who had migrated to New Zealand in 1974, wrote: Emigration is surely a synonym for farewell.

My family and I had said farewell two years earlier to our friends, family, house, work, dog and a lifetime of connections, and I was still in a state of grief. One night in tears I smashed a wine glass on the table, asking my husband when we would be recompensed for everything we had given up to come to New Zealand. He didnt have an answer, but this Welsh migrant did, and his sense of loss, endured and then shared in his personal essay decades later, radiated past the individual to touch me and a larger audience. I realised migrants possess an affinity for the genre whose hallmark is to try, to weigh and to test, even as migrants have tried, weighed, tested and been tested by their chosen country.

One golden summer evening, the last day of term, as I stood in the University of Canterburys beautiful old homestead of Okeover with its high ceilings and French doors opening onto the green lawn, I knew in all my years of teaching I had never taught such a remarkable class. No matter what writing prompt I gave them or how high I set the bar, they cleared it. On that last day, I looked at these 12 students, half of them New Zealanders, half of them migrants from Croatia, Thailand, Switzerland, Wales, the US and Uganda, and realised they were a microcosm of the population of New Zealand, a country with a strong history of migration, both past and present. That first class showed me that the synergy between migrant and the personal essay was akin to dry kindling, strike match. Why were we all here? I wondered, and suddenly I had a purpose again: to see where migration and the personal essay coincided.

I had come to the right country. According to the 2013 census, more than a quarter of New Zealanders were born overseas.

I was a serial migrant and migration had shaped much of my life, but I was also a writer who had been studying, writing and teaching the personal essay for over 20 years. What I found is that migration and the personal essay form a braided river of possibility that deserves to be explored in depth. Both the migrant and the writer set out from what they know towards what they do not, in life and on the page. Charting that voyage of discovery is an endeavour they share in their quest for understanding.

Next page