A HALF CENTURY OF CONFLICT

FRANCE AND ENGLAND IN NORTH AMERICA, VOLUME I

* * *

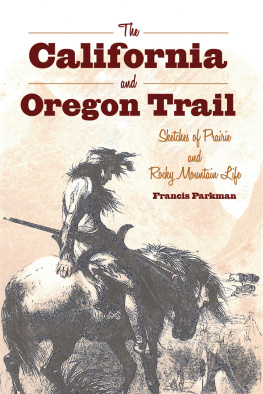

FRANCIS PARKMAN

*

A Half Century of Conflict

France and England in North America, Volume I

First published in 1892

ISBN 978-1-62012-241-9

Duke Classics

2012 Duke Classics and its licensors. All rights reserved.

While every effort has been used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information contained in this edition, Duke Classics does not assume liability or responsibility for any errors or omissions in this book. Duke Classics does not accept responsibility for loss suffered as a result of reliance upon the accuracy or currency of information contained in this book.

Contents

*

Preface

*

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England inNorth America, fills the gap between Part V., "Count Frontenac," andPart VII., "Montcalm and Wolfe;" so that the series now forms acontinuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control thiscontinent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit anunbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in itsbeing throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of thesingularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants toNorth America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents.The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when foundto conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have beensifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each sidehave charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair toneither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series nowcomplete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These havebeen given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts HistoricalSociety, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of thoseinterested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begunforty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow,having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, andfor years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series hasrequired twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorableconditions.

Boston, March 26, 1892.

Chapter I - 1700-1713 - Eve of War

*

The Spanish Succession.Influence of Louis XIV. on History.FrenchSchemes of Conquest in America.New York.Unfitness of the Coloniesfor War.The Five Nations.Doubt and Vacillation.The WesternIndians.Trade and Politics.

The war which in the British colonies was called Queen Anne's War, andin England the War of the Spanish Succession, was the second of a seriesof four conflicts which ended in giving to Great Britain a maritime andcolonial preponderance over France and Spain. So far as concerns thecolonies and the sea, these several wars may be regarded as a singleprotracted one, broken by intervals of truce. The three earlier of them,it is true, were European contests, begun and waged on Europeandisputes. Their American part was incidental and apparently subordinate,yet it involved questions of prime importance in the history of theworld.

The War of the Spanish Succession sprang from the ambition of Louis XIV.We are apt to regard the story of that gorgeous monarch as a tale thatis told; but his influence shapes the life of nations to this day. Atthe beginning of his reign two roads lay before him, and it was amomentous question for posterity, as for his own age, which one of themhe would choose,whether he would follow the wholesome policy of hisgreat minister Colbert, or obey his own vanity and arrogance, and plungeFrance into exhausting wars; whether he would hold to the principle oftolerance embodied in the Edict of Nantes, or do the work of fanaticismand priestly ambition. The one course meant prosperity, progress, andthe rise of a middle class; the other meant bankruptcy and theDragonades,and this was the King's choice. Crushing taxation, misery,and ruin followed, till France burst out at last in a frenzy, drunk withthe wild dreams of Rousseau. Then came the Terror and the Napoleonicwars, and reaction on reaction, revolution on revolution, down to ourown day.

Louis placed his grandson on the throne of Spain, and insulted Englandby acknowledging as her rightful King the son of James II., whom she haddeposed. Then England declared war. Canada and the northern Britishcolonies had had but a short breathing time since the Peace of Ryswick;both were tired of slaughtering each other, and both needed rest. Yetbefore the declaration of war, the Canadian officers of the Crownprepared, with their usual energy, to meet the expected crisis. One ofthem wrote: "If war be declared, it is certain that the King can veryeasily conquer and ruin New England." The French of Canada often use thename "New England" as applying to the British colonies in general. Theyare twice as populous as Canada, he goes on to say; but the people aregreat cowards, totally undisciplined, and ignorant of war, while theCanadians are brave, hardy, and well trained. We have, besides,twenty-eight companies of regulars, and could raise six thousandwarriors from our Indian allies. Four thousand men could easily laywaste all the northern English colonies, to which end we must have fiveships of war, with one thousand troops on board, who must land atPenobscot, where they must be joined by two thousand regulars, militia,and Indians, sent from Canada by way of the Chaudire and the Kennebec.Then the whole force must go to Portsmouth, take it by assault, leave agarrison there, and march to Boston, laying waste all the towns andvillages by the way; after destroying Boston, the army must march forNew York, while the fleet follows along the coast. "Nothing could beeasier," says the writer, "for the road is good, and there is plenty ofhorses and carriages. The troops would ruin everything as they advanced,and New York would quickly be destroyed and burned."

Another plan, scarcely less absurd, was proposed about the same time bythe celebrated Le Moyne d'Iberville. The essential point, he says, is toget possession of Boston; but there are difficulties and risks in theway. Nothing, he adds, referring to the other plan, seems difficult topersons without experience; but unless we are prepared to raise a greatand costly armament, our only hope is in surprise. We should make it inwinter, when the seafaring population, which is the chief strength ofthe place, is absent on long voyages. A thousand Canadians, four hundredregulars, and as many Indians should leave Quebec in November, ascendthe Chaudire, then descend the Kennebec, approach Boston under cover ofthe forest, and carry it by a night attack. Apparently he did not knowthat but for its lean neckthen but a few yards wideBoston was anisland, and that all around for many leagues the forest that was to havecovered his approach had already been devoured by numerous busysettlements. He offers to lead the expedition, and declares that if heis honored with the command, he will warrant that the New Englandcapital will be forced to submit to King Louis, after which New York canbe seized in its turn.

In contrast to those incisive proposals, another French officer breathednothing but peace. Brouillan, governor of Acadia, wrote to the governorof Massachusetts to suggest that, with the consent of their masters,they should make a treaty of neutrality. The English governor beingdead, the letter came before the council, who received it coldly.Canada, and not Acadia, was the enemy they had to fear. Moreover, Bostonmerchants made good profit by supplying the Acadians with necessarieswhich they could get in no other way; and in time of war these profits,though lawless, were greater than in time of peace. But what chieflyinfluenced the council against the overtures of Brouillan was a passagein his letter reminding them that, by the Treaty of Ryswick, the NewEngland people had no right to fish within sight of the Acadian coast.This they flatly denied, saying that the New England people had fishedthere time out of mind, and that if Brouillan should molest them, theywould treat it as an act of war.