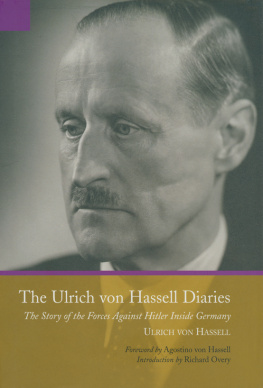

Ulrich von Hassell in 1938. The photo was taken by the personal photographer of Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Hoffmann.

The Ulrich von Hassell

Diaries, 19381944

The Story of the Forces Against

Hitler Inside Germany

Ulrich von Hassell

Foreword by Agostino von Hassell

Introduction by Richard Overy

Translated by Geoffrey Brooks

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut, which is funded by

the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The Ulrich von Hassell Diaries, 19381944

This edition published in 2011 by Frontline Books, an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Limited,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.frontline-books.com

Copyright Ulrich von Hassell, 1947

Introduction copyright Agostino von Hassell, 2011

Foreword copyright Richard Overy, 2011

Notes copyright Friedrich Freiherr von Gaertringen, 1988

The edition Pen & Sword Books Limited, 2011

The right of Ulrich von Hassell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in

accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 978-1-84832-553-1

PUBLISHING HISTORY

The first English-language editions of the Hassell diaries were published in 1947 in the United Kingdom by

Hamish & Hamilton and in the United States by Doubleday & Company with the title The von Hassell

Diaries. The first German-language edition of the diaries was published by Atlantis Verlag in Switzerland

in 1946 with the title Vom Anderen Deutschland. The diaries were later revised and published in the

German language in Germany in 1988 by Wolf Jobst Siedler Verlag Die Hassell-Tagebcher 19381944

with substantial explanatory notes by Friedrich Baron Hiller von Gaertringen, a German historian. Other

editions have been published in Spanish, Austrian, Italian, Danish and French.

This edition published in 2011 by Frontline Books includes a new foreword by Richard Overy and a

translation of Baron Hiller von Gaertringens notes (which retains his references to German language

sources rather than replacing these with references to equivalent English-language works). This edition

also includes an introduction by Ulrich von Hassells grandson, Agostino von Hassell, and a plate section

containing images graciously provided by the von Hassell family.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized

act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP data record for this title is available from the British Library

Typeset in 10pt Minion by Mac Style, Beverley, East Yorkshire

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Mackays

Contents

Plate 1

Ulrich von Hassell, circa 1919

Plate 2

Painting of Ilse von Tirpitz; wedding portrait, 1911; a dance card of Ilse von Tirpitz

Plate 3

Ilse and Ulrich von Hassell in Bavaria; the Hassells shortly after their wedding in 1911

Plate 4

Postcard to Wolf; on the rooftop of the German Consulate, Genoa, Hassell with children

Plate 5

Ulrich von Hassell leaving for the front in the First World War; coat of arms

Plate 6

Hassell and family in Copenhagen, 1929; formal portrait, 1929; Ilse von Hassell, Belgrade, 1930

Plate 7

Ulrich von Hassell in Rome

Plate 8

A trip to the Italian Alps; Ulrich and Ilse von Hassell in Italy

Plate 9

Ulrich von Hassell in Rome with Mussolini; Hassell with Fulco VIII

Plate 10

Hassell family in the Villa Wolkonsky, Rome; Ulrich von Hassell and other diplomats in Rome

Plate 11

Ulrich von Hassell and Mussolini in 1934; Hitler and Mussolini meet for the first time

Plate 12

Ulrich von Hassell at a summer resort in Italy; the Hassells in Italy

Plate 13

A formal portrait of Ulrich von Hassell taken in Italy Plate 14

Trial at the Peoples Court, Berlin, 78 September 1944

Plate 15

Trial at the Peoples Court, Berlin, 78 September 1944; Chief judge Roland Freisler

Plate 16

Ulrich von Hassell with his grandchildren in 1943; Ilse von Hassell

Ulrich von Hassell, German jurist and diplomat, was the Foreign Minister that Germany never had. He was one of a small group of conservative resisters to the Hitler regime who began to plan during the Second World War what a future German government and state might look like. His name on the list of a possible cabinet was always put against that of Foreign Minister, reflecting his lifetimes experience in the world of diplomacy. In the end, his name on the list was a death warrant. After the attempted coup on 20 July 1944, Hassell was arrested, tried for treason and executed on 8 September. This diary, which survived the efforts of the Gestapo to unearth it as evidence, was described by his wife, Ilse, as his bequest and mission when it was first published in Switzerland in 1946.

Hassell was by all accounts a remarkable man who won admirers and friends for his qualities of character and the steadfastness of his beliefs. He was, as one of his close associates, Gottfried von Nostitz, described him, a German nobleman from top to toe. Nostitz recalled Hassells natural, often charming manner, his deep education, his excellent pena cool, sharp mind. It was for these many qualities that he was initially selected as a future minister in a reformed Germany.

Yet Hassell could also make enemies among those who regarded him as a reactionary representative of the traditional Prussian elite (though his family descended from the Hanoverian nobility). His most historically significant post, as German ambassador in Rome from 1932 to 1938, brought him face to face with a young generation of fascists. Italys foreign minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano, thought Hassell unpleasant and treacherous, a surviving relic from that world of Junkers who cannot forget 1914.

These very different judgements on Hassell reflect a profound ambiguity about his own position in the Third Reich, an ambiguity shared by a great many sensible, moral and conservative Germans who found themselves serving Hitler against their will. The central issue that all opponents of the Third Reich had to confront was to measure their own ambitions for Germany against the reality of the dictatorship. Hassell, like thousands of others, wanted to restore a strong German national state and to make it a central engine in a revived Europe; he wanted to revise the Treaty of Versailles and restore Germany fully as a member of the club of Great Powers; he disliked popular politics and communism in particular and was not averse to the idea of an authoritarian state of the old, monarchical kind that he had first served as a young man before 1914. In 1933 he joined the National Socialist party, though with reservations, and in his capacity as ambassador in Italy sought to revive Germanys international fortunes and prepare for the revision of Versailles. Much of what was achieved in the 1930s, including the Anschluss with Austria, German re-militarisation, the incorporation of the Sudeten Germans in 1938, Hassell would have agreed with. This was, as he describes it in his diary, the tragic conflict that German nationalists had to face. He explored that inner turmoil in his diary in a memorable passage from August 1942 in which he put side by side the terrible clarity about the fearful destruction of all true values in Germany and the world with the picture of military successes on all fronts (p. 168). He did not want Germany utterly defeated, but nor could he imagine a triumphant Hitler. In June 1940, after the complete defeat of France, he recorded in his diary that for him it was tragic not to be able to rejoice over such triumph (p. 95).