To Hamish, who started it all.

No character in this book is fictitious.

I

Arrochar is not a beautiful village at the best of times; but on this particular Saturday afternoon in 1933 trippers had added to its normal air of untidiness. A steamer had disgorged several hundreds on to the pier and was pounding down Loch Long for more; a squadron of empty buses was drawn up outside the principal hotel, awaiting passengers whose attention was divided between high teas and beer; and the local ice cream merchants barrow was besieged. A tinker with bagpipes blasted his way along the waterfront, followed by a small and rapacious daughter extorting pennies. Sandwich papers littered the shore where groups of women, by sheer force of character making this alien spot a Glasgow park, alternately ate, gossiped, and turned to scold the children who sought crabs among the rocks. The dominant smell was equal parts of salt sea, dusty tar, and petrol.

But Arrochar, for all its air of cheap bustle, could not conceal the fact that it existed on the fringe of tripper land, that it was an outpost among the resorts dotted about the Firth of Clyde to cater for the weekends and summer holidays of Glasgow. The bustle was confined to a narrow strip along the shores of Loch Long. Above and beyond were mountains, scarcely touched by the tidemark of humanity at their bases, impervious to pipers and ice cream barrows or to the customers of either, as aloof and untouched as the desert which hems in the airport of Timbuctoo.

Through the crowds by the pier John and I walked slowly, saying nothing and trying to accommodate our minds to the idea that we were not alone. We watched perspiring women weigh themselves on penny in the slot machines, and heard the cheerful hubbub of Glasgow enjoying itself. We saw children, saved from the wheels of buses, being spanked out of hand in sheer relief. People noticed our rucksacks, and cried, Aw, the hikers! and to these people we smiled; but neither of us spoke until we had bought ice cream and sat upon the sea wall to eat it.

This, said John, is very unfortunate.

It was. The little camping we had done had been done near Glasgow; and for this, our first ambitious excursion on our own, we had tried to select a quiet district off the main tourist and tripper routes. Arrochar had looked quiet on the map. And here we were. We fell silent again while we ate our ice cream, watched bus after bus spew forth its cargo, and wondered if anywhere in the distance there was a campsite beyond earshot of bagpipes and squalling infants. Depression settled on us as on an Everest expedition which, having turned along the wrong glacier, finds itself on Brighton Pier.

I dont think much of that either, said John, waving a hand towards the far shore of the loch, where a mile of tents cluttered up the roadside; wife beating and harmoniums till two in the morning, Ill be bound.

Above the distant strip of tents rose Ben Arthur, a mountain commonly called the Cobbler even by those, and I am one, who have never been able to see the slightest resemblance to a cobbler in any of the three crazy pinnacles which cap it. A devious road wound along the loch shore, lapped on one side by the water and on the other by the grey- white froth of tents. Above rose steep, bracken-covered slopes which, tiring in their upward sweep, gained strength on a level shelf of ground before soaring once more to the three pinnacles which lurched across the skyline. It was a striking mountain. We were distracted by many more immediate and noisy features of the landscape, but always we were drawn back to it and to the high, level shelf cut into its side. We began to look at it thoughtfully.

I suppose we could get a tent up there, said John at last in a way which suggested that he had his doubts.

We considered this.

Why not? I asked.

John looked at the Cobbler and then at his rucksack, weighing the angle of one against the bulk of the other, and both, it seemed, against the heat of the sun. He smiled.

Come on, he said, and swung his rucksack on to his shoulders.

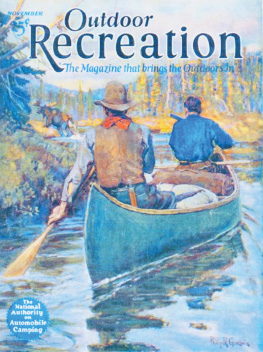

At five oclock we left the road and started up the left bank of the burn which drains the Arrochar face of the Cobbler. The afternoon was excessively hot, and the weight we were carrying was ludicrous. We had yet to learn that heavy pots and pans, thick ground sheets, raincoats, and much tinned food are luxuries to be avoided upon a mountain, just as we had yet to learn that there was an excellent path on the far side of the burn. On our bank, bracken grew with the abandon popularly associated with machetes and tropical jungles, and in some places was taller than we were ourselves. Forcing a passage through it while carrying a heavy rucksack up a steep slope was trying. Also, there were flies. The first thousand feet was a purgatory of heavy breathing, sweat, and the forlorn beauty of bracken fronds against the sky; but higher up the bracken thinned. We cast ourselves down on a bank of heather and bog myrtle, propped our shoulders against a rock, and looked down on Loch Long, where cars crawled along the road and a steamer unloaded another ice cream-less multitude. The sun was still very hot, and the air reeked with the tang of bog myrtle against a background of other mingled and satisfactory smells. Sounds were faint and Arrochar distant. Everything was remote, peaceful, and unreal.

Suddenly a commotion arose among the crowds on the pier. They parted and put forth a white figure which shot from the edge of the pier, poised for an instant in mid air, and began to drop gracefully towards the water.

It is strange, now, to look back and realise that I wondered who the diver could be, that in those days I did not know anyone who would cast himself from a pier at low tide for no other reason than that it was Saturday, with the city fifty miles away and the rush of warm air on downward face a joy. It is strange, too, to realise how much in character Hamish was that first time I saw him, strange because now the incident takes its place at the end of a long perspective of incidents which give it a relevancy it did not possess at the time Hamish on the Crowberry Ridge, with sleet whipping across the streaming hand holds, eighty feet of air below his boots and battle in his eye; Hamish hanging over a map, tracing out some fantastic route and scoffing at the doubters Och, dont be daft, man. Of course, its possible! Hamish in Dan Mackays barn, arguing with tramps; Hamish on his preposterous motorbike; Hamish in the Chasm; Hamish the eternal optimist, tingling with excitement in a dozen situations when a plot was afoot and enthusiasm in the air.

All these things were latent in the tiny figure poised above Loch Long; but we watched with only mild interest as the dive ended and he clipped out into the open water. The seaward edge of the pier was black with spectators, who, judging by the noises which reached us, were either shouting encouragement or expressing disapproval. Disapproval was the more likely, because the loch was nearly a mile wide and the little figure did not turn back until he was more than halfway across. There was a momentary revival of interest when he scrambled up the shore, and then attention turned to other things. John and I plodded on uphill.

We did not pitch our tent until nearly eight oclock, and even then did not reach the level ground, though the sun was less hot and the going easier. We were unused to carrying loads, and when we came on two enormous boulders and a level patch of ground beside the burn, we stopped. Twenty minutes later we had the stove going. The tent door faced the summit. The three pinnacles were gigantic fingers, black against the sunset. Nothing stirred. Arrochar and all its works were out of sight below the skyline, and there was silence.