Contents

Guide

WHITE TERROR

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.org

2022 by Russell Meeuf

, Motor City Gothic: White Youth and Economic Anxiety in It Follows and Dont Breathe by Russell Meeuf and Benjamin James originally appeared in Dark Forces at Work: Essays on Social Dynamics and Cinematic Horrors (Lexington Books, 2019) and is reprinted with permission.

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Manufactured in China

First printing 2022

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-06037-2 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-253-06038-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-06039-6 (ebook)

CONTENTS

THIS PROJECT WAS ORIGINALLY A collaboration with my amazing friend and colleague Ben James, a screenwriter with a keen interest in horror storytelling. Ben and I developed the concept for this book together while co-teaching a freshman seminar on US horror films. We wanted to write an accessible book to help students, scholars, and horror fans grapple with the role of race and White racial anxieties in contemporary US horror films. Ben was pulled away from the project by his creative work (writing and directing a short horror film about corruption in rural White communities, appropriately enough), but this project has been informed by his insights and ideas from the very start.

My editor at Indiana University Press, Allison Chaplin, was also instrumental in supporting this project, and her suggestions along the way about how to create a scholarly book that is accessible and engaging to general audiences have been immensely helpful. The readers who supplied feedback on the project also provided invaluable suggestions.

I was also supported by a wonderful network of friends and colleagues who suggested great readings on horror and other topics, watched and discussed horror films with me, and generally provided moral support while I spent much of my professional life ensconced in a world of haunted houses, demonic possession, and creepy children: Jon Hegglund, Chad Burt, Zach Turpin, Dylan Champagne, Kevin Lewallen, Doug Heckman, Jenn Ladino, Erin James, and others. My department at the University of Idaho also supported my work here over the past several years, especially Kenton Bird, Pat Hart, Robin Johnson, Katie Blevins, Caitlin Cieslik-Miskimen, and Kyle Howerton. Special thanks to Carter Soles for sharing some of his recommendations on horror research and to Johanna Gosse for recommending some amazing research on race and surveillance culture that informs . Chris Holmlund also provided support, suggestions, and a friendly ear as I finished the project.

The Society for Cinema and Media Studies Horror Studies Scholarly Interest Group was also invaluable, especially the folks who participated in the Facebook group and helped answer many queries over the years. Many thanks to Murray Leeder for his leadership with that group.

A version of appeared in the book Dark Forces at Work: Essays on Social Dynamics and Cinematic Horrors, edited by Cynthia J. Miller and A. Bowdoin Van Riper and published by Lexington Books. Many thanks to the editors of the collection for their suggestions on that chapter.

And, as always, the biggest thanks go to Ryanne, my partner and best friend, who cant watch horror movies but cheerfully discussed them with me while helping me raise three (hopefully non-creepy) children. During the time it took me to write this book, Alden went from being a little boy who couldnt get through the first jump scares of a horror movie to a teenager who doesnt think they are scary enough; Will has slowly graduated to watching PG-13 horror films, only needing to cover his eyes occasionally; and Fern (no surprise) has decided that nothing can possibly scare her.

WHITE TERROR

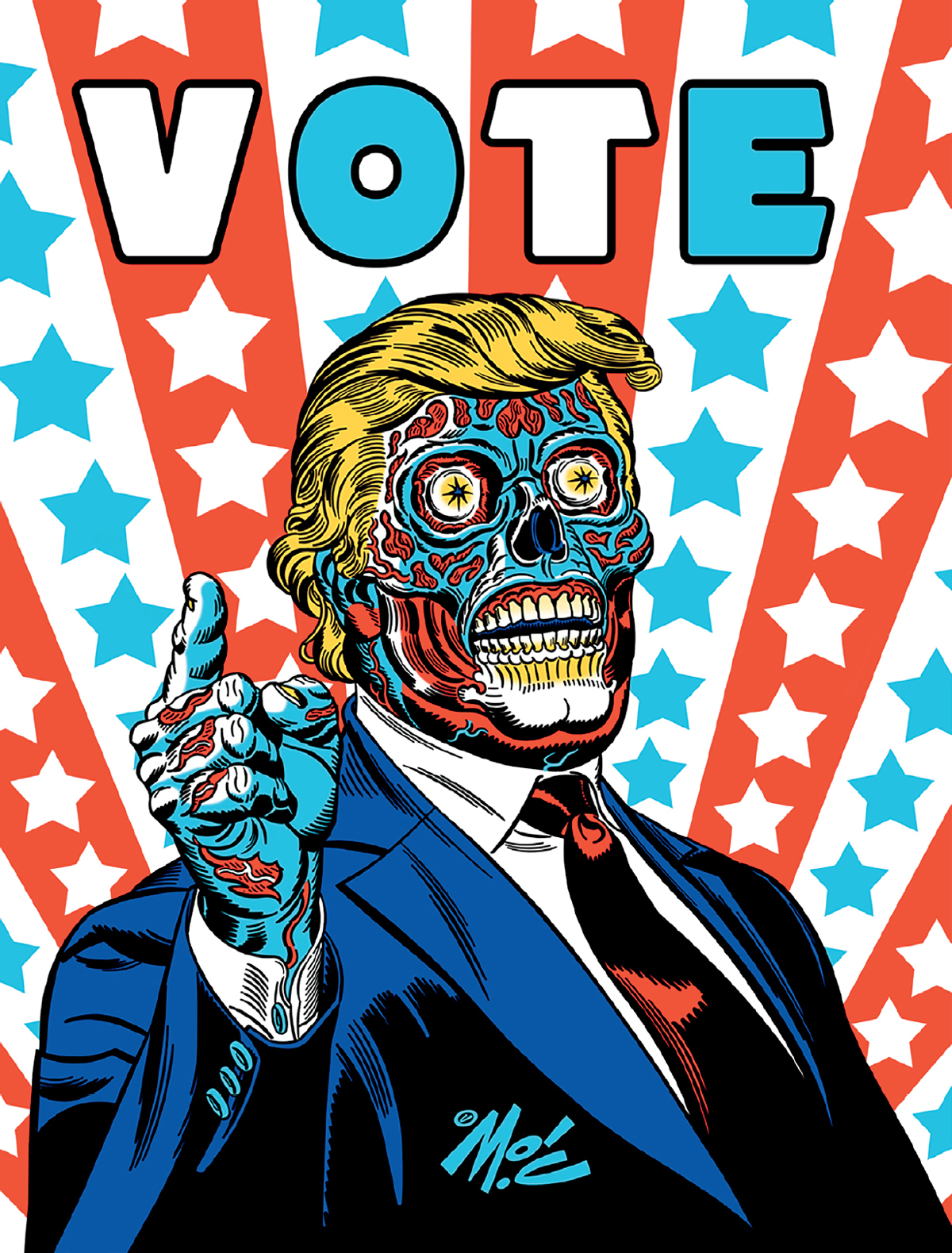

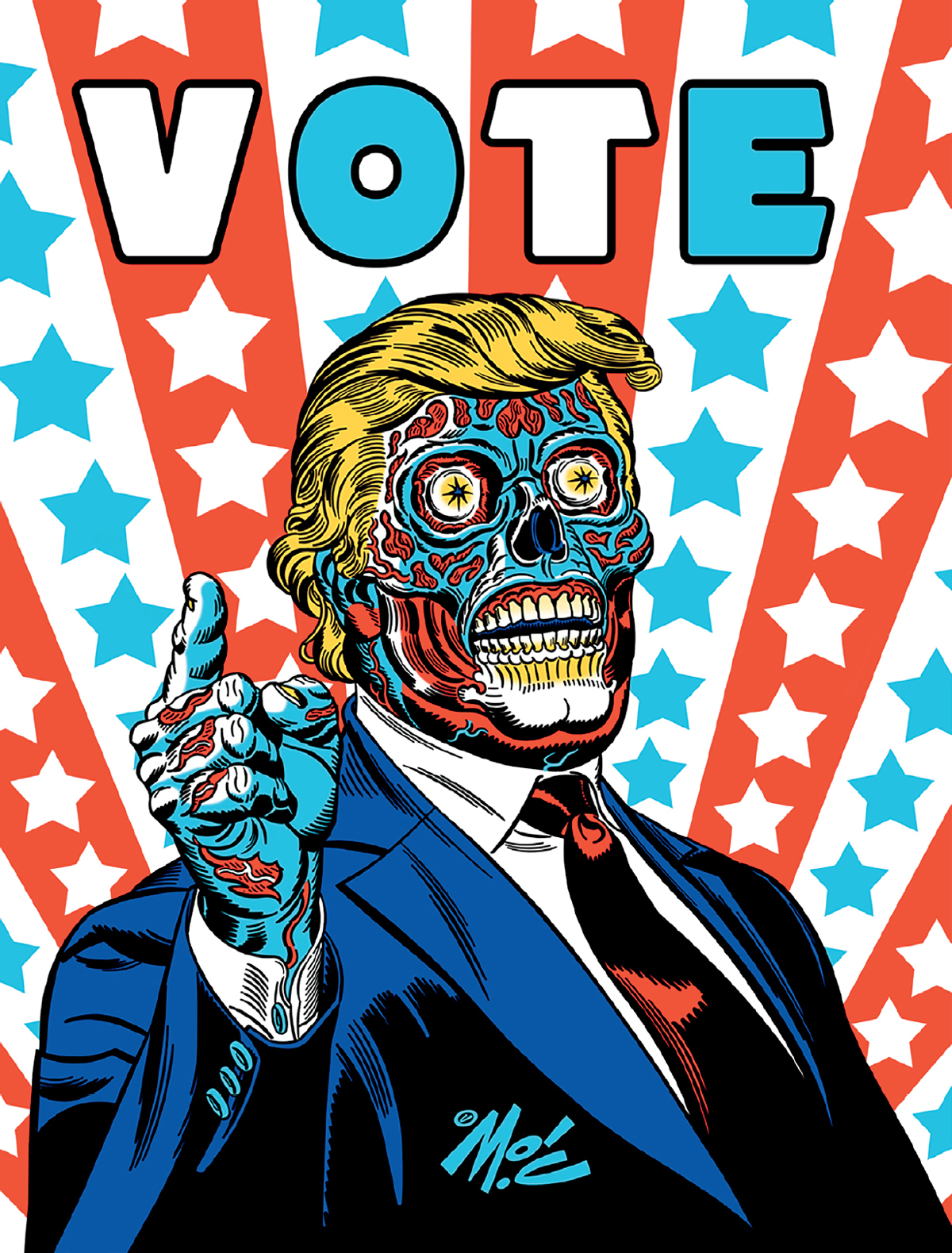

IN THE FIRST YEARS OF Donald Trumps presidency, activists and critics turned to the imagery of horror to encapsulate what was, to them, the nightmare of a President Trump. Chicago artist Mitch OConnell began creating and circulating images of Trump in the style of the secret alien overlords in John Carpenters They Live (1988); when seen with special glasses, the faces are revealed to be horrific, blue-tinged skulls (see ). OConnell created the images early in the presidential campaign and raised money for Trump Lives! billboards after the election.

Meanwhile, a trypophobia-inducing picture of Trumps head, pocked with holes containing Steve Bannons face, made the rounds on Reddit and other social-media outlets. And when Melania Trump unveiled the somewhat unorthodox Christmas decor for the White House in 2017, internet Photoshoppers took the liberty of drawing connections to classic horror movies (see ), a theme repeated in 2018, when she unveiled a hallway of blood-red Christmas trees.

For many Americans, the spectacle of horror became a fitting lens through which to view the political realities of a blustering, often-vulgar president who embraced deception and race-baiting. As the Trump presidency became mired in a never-ending series of scandals and crass tweets in its first years, the grim and unsettling worldview of horror mirrored our eroding political norms. American politics has, of course, long abandoned the pretense of civil discourse, but for many people, the ascendency of Trump created a horrific bizarro world. Ideal political norms, even if rarely achieved, were turned on their heads. Policy debates were replaced with bluster. Careful analysis was replaced with alternative facts. The rhetoric of respect gave way to explicit sexism and xenophobia. In the age of Trump, US political culture didnt even pretend to valorize traditional norms; with the veil of tradition cast aside, it was revealed to be a farce, behind which stood only opportunism, corruption, and hate.

Fig. I.1. Mitch OConnells rendering of Trump as an alien overlord from 1988s They Live, using the lens of horror to express the political horrors of Trumpism.

Fig. I.2. Left: An image of Trumps face filled with holes containing Steve Bannon that circulated on Reddit in 2017. Right: A meme that placed Jack Torrance from The Shining into Melania Trumps Christmas decor in 2017.

The uncanny media coverage of a president who is anything but presidential lent itself well to the uncanny world of horror, where everything that should be life-affirming and reassuringfamily, home, religion, social institutionsis a grim inversion of its ideal form, marked by decay, immorality, and death.

Next page